WITTENBERG CAMP

PARCELS FROM HOME

A SPORTS GROUND, BUT NO SPORT.

http://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/british-and-german-prisoners-6mgxsrm23

British and German Prisoners

The British prisoners appear to be singled out from those of other nationalities for harsh and humiliating treatment

April 12, 1915

The treatment accorded to prisoners of war, and particularly to wounded prisoners of war, is justly regarded as a test of the civilization which exists amongst their captors. The savage regards his captives as objects upon which it is his right and his pleasure to exercise his cruelty and his hate. The nations of Christendom, whose customs in warfare are still largely based upon the traditions of chivalry, look upon their prisoners as honourable foes, against whom they cherish no personal ill-will, and to whom honour and self-respect oblige them to extend all the consideration and the courtesy compatible with safe keeping.

The gradual amelioration in the lot of the captured, like the growth of other humane practices in the conduct of war, has been hitherto considered by all peoples who have emerged from barbarism as amongst the chief tokens of the progress of the world. The regulations annexed to The Hague Convention of October 18, 1907, were welcomed by them, as giving a solemn international sanction to principles and practices which the most cultivated nations have long followed during hostilities as a matter of course. It was with wonder and, indeed, with a large measure of incredulity, that the English peoples received the first reports which reached them that the Germans had flung these traditions to the winds, that they were treating British prisoners, and even wounded prisoners, with cruelty and insult, and that they were showing the same contempt for The Hague regulations as for other “scraps of paper”.

We may hope, even still, that some of the stories which have been received are exaggerated, and that the worst conduct described in them has not been general. It seems, however, impossible, in the face of the evidence contained in the recent White Paper, and strongly corroborated from other sources, to doubt that Germany, with all her Kultur, has relapsed into brutalities towards her English captives, without parallel in the modern history of war.

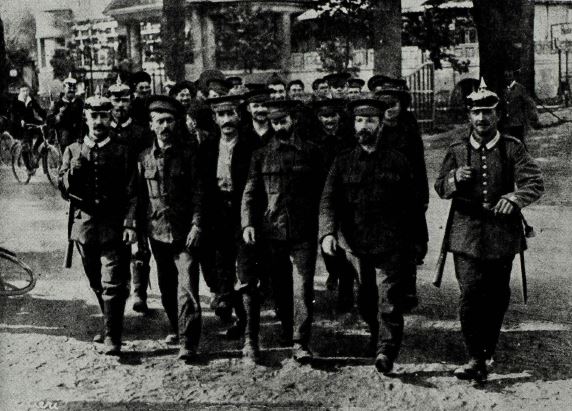

Sir Edward Grey’s dispatch of December 26 and the papers annexed to it, especially Major Vandeleur’s reports, appear to be conclusive in this respect. Major Vandeleur is himself an escaped prisoner, who speaks of what he himself saw and heard. Sir Edward Grey expresses his conviction that the American Ambassador, to whom he forwarded the paper, could not fail to be impressed by its “evident veracity and sincerity”. All who read it, we imagine, will share this impression. The most painful part of the report is that which relates to the journey of the prisoners from the front into Germany. They were constantly abused and reviled. One German officer showed his manliness and breeding by spitting upon a defenceless British officer. Officers and men were herded together into foul horse-boxes. All along the line German officers as well as soldiers cursed them. Their greatcoats were stolen in the bitter cold, and their guards opposed the charitable efforts of the French Red Cross to supply them with food. At one Station Major Vandeleur was dragged out of the wagon, cursed in filthy language by another of these German “gentlemen” wearing the Kaiser’s coat, and then kicked at this brute’s orders by a common soldier. Such are the humanity and the politeness, of which the German military caste, the men who exact from mere civilians amongst their own countrymen cringing respect for their uniform, are capable towards a wounded and defenceless English gentleman.

Only once did Major Vandeleur hear an officer try to restrain the curses of his men. The prisoners were cooped up in these over-crowded and unventilated wagons for three days and three nights. In the Crefeld Camp, where Major Vandeleur was confined, no gross physical hardships are complained of. The officers were overcrowded, and they had, for the most part, to make their own beds and to black their own boots. The treatment of the rank and file imprisoned at other places is described as “barbarous”.

Major Vandeleur’s information in regard to it comes from British orderlies transferred to Crefeld as officers’ servants, and from English and French medical officers. The men were deprived of their greatcoats and their money, and often of their tunics. All the orderlies reached Crefeld crawling with vennin and many were suffering from the itch. They said that they were half-starved, and they looked half-starved. One of the reports by Americans appended to the dispatch declares they are “kept on very short commons”; another that they are pale from want of food and “vermin-ridden”, while the floors of their tents are “a mass of mud”.

Sir Edward Grey draws attention to the fact that the British prisoners appear to be singled out from those of other nationalities for harsh and humiliating treatment. This view is fully borne out by Major Vandeleur. The French prisoners were fed on the terrible journey from the front; the British got the leavings. All the menial and dirty work of the camps is assigned to our countrymen, and Major Vandeleur declares it to be his strong opinion that the particular brutality shown to them on the way there “is deliberately arranged for by superior authority”. The French officers, he states, “were treated quite differently”. This view is supported by the evidence of a Russian doctor and of a French priest.

The report of Mr John B Jackson, of the American Embassy in Berlin, upon the position of German prisoners and interned Germans in this country forms a contrast to these statements, upon which we may look with satisfaction and with pleasure. It shows that we have not been unmindful of what we owe to ourselves and to our opponents. The German officers without exception told Mr Jackson that they “had always been treated like officers and honourable men,” and many of the soldiers informed him that British soldiers had protected them from insult as they passed through France. Nowhere did this neutral observer, who had the fullest opportunities for conversing with the prisoners apart, discover any signs of a desire to make their condition harder or more disagreeable than was necessary. As to “Donington Hall,” it is, he declares, “a beautiful place”. That is the way in which England treats her German prisoners. It is the way in which she would have expected Germany to treat captive Englishmen.

That expectation has been disappointed. Germany has shown no respect for misfortune or for suffering, for rank or for the uniform which, in the past, has everywhere appealed to soldiers’ hearts. She has striven in many cases, and striven, it must be feared, of set purpose to inflict needless pain and undeserved humiliation on our brave countrymen. The degradation is not theirs, but her own.

She has heaped fresh disgrace upon her name, and disgrace which we should have supposed would have been felt with peculiar keenness by a military nation. She has shown that she disregards the common humanities and the honourable courtesies of soldiers to each other, as utterly as she despises the rights of civilians and the obligations of international law.

http://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/our-prisoners-in-germany-wf5qbt3vf

The gradual amelioration in the lot of the captured, like the growth of other humane practices in the conduct of war, has been hitherto considered by all peoples who have emerged from barbarism as amongst the chief tokens of the progress of the world. The regulations annexed to The Hague Convention of October 18, 1907, were welcomed by them, as giving a solemn international sanction to principles and practices which the most cultivated nations have long followed during hostilities as a matter of course. It was with wonder and, indeed, with a large measure of incredulity, that the English peoples received the first reports which reached them that the Germans had flung these traditions to the winds, that they were treating British prisoners, and even wounded prisoners, with cruelty and insult, and that they were showing the same contempt for The Hague regulations as for other “scraps of paper”.

We may hope, even still, that some of the stories which have been received are exaggerated, and that the worst conduct described in them has not been general. It seems, however, impossible, in the face of the evidence contained in the recent White Paper, and strongly corroborated from other sources, to doubt that Germany, with all her Kultur, has relapsed into brutalities towards her English captives, without parallel in the modern history of war.

Sir Edward Grey’s dispatch of December 26 and the papers annexed to it, especially Major Vandeleur’s reports, appear to be conclusive in this respect. Major Vandeleur is himself an escaped prisoner, who speaks of what he himself saw and heard. Sir Edward Grey expresses his conviction that the American Ambassador, to whom he forwarded the paper, could not fail to be impressed by its “evident veracity and sincerity”. All who read it, we imagine, will share this impression. The most painful part of the report is that which relates to the journey of the prisoners from the front into Germany. They were constantly abused and reviled. One German officer showed his manliness and breeding by spitting upon a defenceless British officer. Officers and men were herded together into foul horse-boxes. All along the line German officers as well as soldiers cursed them. Their greatcoats were stolen in the bitter cold, and their guards opposed the charitable efforts of the French Red Cross to supply them with food. At one Station Major Vandeleur was dragged out of the wagon, cursed in filthy language by another of these German “gentlemen” wearing the Kaiser’s coat, and then kicked at this brute’s orders by a common soldier. Such are the humanity and the politeness, of which the German military caste, the men who exact from mere civilians amongst their own countrymen cringing respect for their uniform, are capable towards a wounded and defenceless English gentleman.

Only once did Major Vandeleur hear an officer try to restrain the curses of his men. The prisoners were cooped up in these over-crowded and unventilated wagons for three days and three nights. In the Crefeld Camp, where Major Vandeleur was confined, no gross physical hardships are complained of. The officers were overcrowded, and they had, for the most part, to make their own beds and to black their own boots. The treatment of the rank and file imprisoned at other places is described as “barbarous”.

Sir Edward Grey draws attention to the fact that the British prisoners appear to be singled out from those of other nationalities for harsh and humiliating treatment. This view is fully borne out by Major Vandeleur. The French prisoners were fed on the terrible journey from the front; the British got the leavings. All the menial and dirty work of the camps is assigned to our countrymen, and Major Vandeleur declares it to be his strong opinion that the particular brutality shown to them on the way there “is deliberately arranged for by superior authority”. The French officers, he states, “were treated quite differently”. This view is supported by the evidence of a Russian doctor and of a French priest.

The report of Mr John B Jackson, of the American Embassy in Berlin, upon the position of German prisoners and interned Germans in this country forms a contrast to these statements, upon which we may look with satisfaction and with pleasure. It shows that we have not been unmindful of what we owe to ourselves and to our opponents. The German officers without exception told Mr Jackson that they “had always been treated like officers and honourable men,” and many of the soldiers informed him that British soldiers had protected them from insult as they passed through France. Nowhere did this neutral observer, who had the fullest opportunities for conversing with the prisoners apart, discover any signs of a desire to make their condition harder or more disagreeable than was necessary. As to “Donington Hall,” it is, he declares, “a beautiful place”. That is the way in which England treats her German prisoners. It is the way in which she would have expected Germany to treat captive Englishmen.

That expectation has been disappointed. Germany has shown no respect for misfortune or for suffering, for rank or for the uniform which, in the past, has everywhere appealed to soldiers’ hearts. She has striven in many cases, and striven, it must be feared, of set purpose to inflict needless pain and undeserved humiliation on our brave countrymen. The degradation is not theirs, but her own.

She has heaped fresh disgrace upon her name, and disgrace which we should have supposed would have been felt with peculiar keenness by a military nation. She has shown that she disregards the common humanities and the honourable courtesies of soldiers to each other, as utterly as she despises the rights of civilians and the obligations of international law.

http://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/our-prisoners-in-germany-wf5qbt3vf

Our Prisoners in Germany

If the Red Cross desires to continue to possess the confidence of its millions of admirers and supporters all over the world it must not fail to compel obedience and respect for its declared principles affecting the treatment of prisoners and captives

April 26, 1916

To the Editor of The Times

Sir, It is not difficult to account for the fact that, until quite recently, the British Press and public have given so little attention to the bitter case of British prisoners in German camps. Hitherto we have been led to believe that, taken all round, the American Embassy in Berlin is satisfied that our men have not very much to complain of, that things are better than they were, and that the state of our imprisoned soldiers is at least not worse than that of their French and Russian fellow captives. But our doubts are increasing.

We know, of course, that many reports have been received by our Government from the Americans since the beginning of this year; but, although these concern our own kith and kin, we have not yet been allowed to read them in full and must rest content with such inferences and short summaries as appear in the Press from time to time. We are becoming sceptical.

The Wittenberg report lifted a corner of the veil and deepens our disquietude. For it does not explain why, when the Americans were refused permission to visit that camp, our Government did not immediately appeal to the International Red Cross Society at Geneva to send a posse of neutral doctors to deal with the epidemic. One wonders how long our Foreign Office knew of that ghastly condition of things; even the Americans either did not know or they failed to report it.

Lord Robert Cecil suggested in Parliament the other day that the Wittenberg brutalities were probably an exception, but this is far from being the truth. Reports of similar epidemics, fatal to Russian, French, and British prisoners alike, have been received in France (if not in England) from Schneidemühle, Gardelegen, Gastrow, Langensalza, and Niederzwheren; the same story of German professional cowardice runs through nearly all of them. Had our Government, or any of its departments or committees or sub-committees which affect the care of our prisoners, no knowledge of these facts, upon which the British Medical Journal commented months ago?

GENEVA HEADQUARTERS.

And now your leading article of the 22nd inst hints, not obscurely, at unfavourable reports from Bulgaria and from Turkey. Neutral travellers, recently returned from both countries, confirm your fears. Yet, all this time, the belated negotiations about internment in Switzerland are dragging along, as though no question of saving human life was connected with them, while German prisoners are living a State-controlled existence of idleness and luxury in England! The tragedy of our prisoners’ lot “lies too deep for tears”; it is time for a united protest to be addressed to the British Red Cross Society, asking it to appeal to the International Headquarters of that organization at Geneva, begging them instantly to intervene and to champion the cause of the Geneva and later Conventions; to call a conference, if need be, of neutral Powers to insist, in the name of international humanity, upon the prompt execution of those obligations in respect of prisoners to which all the present belligerents were signatories, but which some have apparently forgotten.

The reputation not only of Governments, but of the Red Cross Confraternity, is at stake; if the latter desires to continue to possess the confidence of its millions of admirers and supporters all over the world it must not fail to compel obedience and respect for its declared principles affecting the treatment of prisoners and captives.

The Red Cross, an international organization, is on its trial, not as an ornament of peacetime, but as an essential institution in time of war. In many directions it has already gained imperishable fame; it will add lustre to its reputation if it speaks now to the whole world ex cathedra from Geneva and exacts humane, nay generous, treatment for all prisoners of war.

Yours faithfully, CARITAS.

http://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/wittenberg-horrors-6jdwvlkwd

Sir, It is not difficult to account for the fact that, until quite recently, the British Press and public have given so little attention to the bitter case of British prisoners in German camps. Hitherto we have been led to believe that, taken all round, the American Embassy in Berlin is satisfied that our men have not very much to complain of, that things are better than they were, and that the state of our imprisoned soldiers is at least not worse than that of their French and Russian fellow captives. But our doubts are increasing.

We know, of course, that many reports have been received by our Government from the Americans since the beginning of this year; but, although these concern our own kith and kin, we have not yet been allowed to read them in full and must rest content with such inferences and short summaries as appear in the Press from time to time. We are becoming sceptical.

The Wittenberg report lifted a corner of the veil and deepens our disquietude. For it does not explain why, when the Americans were refused permission to visit that camp, our Government did not immediately appeal to the International Red Cross Society at Geneva to send a posse of neutral doctors to deal with the epidemic. One wonders how long our Foreign Office knew of that ghastly condition of things; even the Americans either did not know or they failed to report it.

Lord Robert Cecil suggested in Parliament the other day that the Wittenberg brutalities were probably an exception, but this is far from being the truth. Reports of similar epidemics, fatal to Russian, French, and British prisoners alike, have been received in France (if not in England) from Schneidemühle, Gardelegen, Gastrow, Langensalza, and Niederzwheren; the same story of German professional cowardice runs through nearly all of them. Had our Government, or any of its departments or committees or sub-committees which affect the care of our prisoners, no knowledge of these facts, upon which the British Medical Journal commented months ago?

And now your leading article of the 22nd inst hints, not obscurely, at unfavourable reports from Bulgaria and from Turkey. Neutral travellers, recently returned from both countries, confirm your fears. Yet, all this time, the belated negotiations about internment in Switzerland are dragging along, as though no question of saving human life was connected with them, while German prisoners are living a State-controlled existence of idleness and luxury in England! The tragedy of our prisoners’ lot “lies too deep for tears”; it is time for a united protest to be addressed to the British Red Cross Society, asking it to appeal to the International Headquarters of that organization at Geneva, begging them instantly to intervene and to champion the cause of the Geneva and later Conventions; to call a conference, if need be, of neutral Powers to insist, in the name of international humanity, upon the prompt execution of those obligations in respect of prisoners to which all the present belligerents were signatories, but which some have apparently forgotten.

The reputation not only of Governments, but of the Red Cross Confraternity, is at stake; if the latter desires to continue to possess the confidence of its millions of admirers and supporters all over the world it must not fail to compel obedience and respect for its declared principles affecting the treatment of prisoners and captives.

The Red Cross, an international organization, is on its trial, not as an ornament of peacetime, but as an essential institution in time of war. In many directions it has already gained imperishable fame; it will add lustre to its reputation if it speaks now to the whole world ex cathedra from Geneva and exacts humane, nay generous, treatment for all prisoners of war.

Yours faithfully, CARITAS.

http://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/wittenberg-horrors-6jdwvlkwd

Wittenberg horrors

Dr Destrée, who was himself stricken with typhus on March 8, states that the mortality among the doctors was: Russians, 20 per cent, French, 75 per cent, British, 75 per cent

July 26, 1916

We are able through the courtesy of the Bureau Documentaire Belge to supplement in some particulars the story of the crime of Wittenberg as revealed in the report of the British Committee published in The Times of April 10.

Two Belgian medical men, Dr Destrée and Dr Bolland, were in contravention of the Geneva Convention transferred to Wittenberg in October, 1914, and the testimony of Dr Destrée as to the condition of the camp before the arrival of the British officers is available. Dr Destrée’s report of his experiences and those of his colleague bears out to the full the charges brought by the British doctors.

All the efforts they made to get the authorities to separate the French and Russian prisoners were fruitless, notwithstanding the warnings as to the spread of epidemics which would result from the herding of the men together. In December, 1914, cholera broke out in the camp, and Drs Destrée and Bolland asked for overalls, bandages, and soap; these were refused by Dr Aschenbach, the chief medical officer of the camp. A French medical officer, Dr Tritschler, having asked that the doctors should receive better treatment, was as a disciplinary measure made to act as night guard at the Russian infirmary, where he had to sleep with the patients.

When in January 1915 typhus made its appearance Dr Aschenbach, after telling each medical man what he had to do, left the camp. A Russian, Dr Schigatchoff, was put in charge, and his sole means of communicating with Dr Aschenbach was by telephone. Notwithstanding repeated and insistent demands made by Dr Schigatchoff nothing was supplied - beds, bedding, linen, light, all were lacking. On January 19 Dr Bolland and two Russian doctors fell ill; on January 21 Dr Tritschler died. It was at this crisis, with the typhus increasing, that the British medical officers were brought into the camp.

The story from this point resembles that in the British report. Dr Destrée, who was himself stricken with typhus on March 8, states that the mortality among the doctors was: Russians, 20 per cent; French, 75 per cent, British, 75 per cent. The insufficiency and bad quality of the food supplied caused many cases of tuberculosis, especially among those convalescent from typhus.

Dr Destrée adds: Hundreds of prisoners were the victims of these abominations committed at Wittenberg by German barbarity. Thousands of unfortunates are there to-day exposed to all privations and to the brutality of their guardians. Particulars (which agree with the British report) are given with regard to food and lodging, both of the ordinary prisoners and of the doctors. The doctors were lodged for five months in the prisoners’ barracks, and up to the end of November were refused fires. Correspondence was suppressed, and medicines which they asked for and paid for themselves for their sick colleagues arrived a week after their death.

Dr Destrée also states that several prisoners were the victims of serious assaults, and that the protests of the doctors against this maltreatment were disregarded. In September, 1915, Dr Destrée was transferred to the camp at Zerbst, where he remained until January, 1910. At Zerbst conditions were better. The full text of Dr Destrée’s report will be published shortly by the Belgian Government.

Two Belgian medical men, Dr Destrée and Dr Bolland, were in contravention of the Geneva Convention transferred to Wittenberg in October, 1914, and the testimony of Dr Destrée as to the condition of the camp before the arrival of the British officers is available. Dr Destrée’s report of his experiences and those of his colleague bears out to the full the charges brought by the British doctors.

All the efforts they made to get the authorities to separate the French and Russian prisoners were fruitless, notwithstanding the warnings as to the spread of epidemics which would result from the herding of the men together. In December, 1914, cholera broke out in the camp, and Drs Destrée and Bolland asked for overalls, bandages, and soap; these were refused by Dr Aschenbach, the chief medical officer of the camp. A French medical officer, Dr Tritschler, having asked that the doctors should receive better treatment, was as a disciplinary measure made to act as night guard at the Russian infirmary, where he had to sleep with the patients.

When in January 1915 typhus made its appearance Dr Aschenbach, after telling each medical man what he had to do, left the camp. A Russian, Dr Schigatchoff, was put in charge, and his sole means of communicating with Dr Aschenbach was by telephone. Notwithstanding repeated and insistent demands made by Dr Schigatchoff nothing was supplied - beds, bedding, linen, light, all were lacking. On January 19 Dr Bolland and two Russian doctors fell ill; on January 21 Dr Tritschler died. It was at this crisis, with the typhus increasing, that the British medical officers were brought into the camp.

The story from this point resembles that in the British report. Dr Destrée, who was himself stricken with typhus on March 8, states that the mortality among the doctors was: Russians, 20 per cent; French, 75 per cent, British, 75 per cent. The insufficiency and bad quality of the food supplied caused many cases of tuberculosis, especially among those convalescent from typhus.

Dr Destrée also states that several prisoners were the victims of serious assaults, and that the protests of the doctors against this maltreatment were disregarded. In September, 1915, Dr Destrée was transferred to the camp at Zerbst, where he remained until January, 1910. At Zerbst conditions were better. The full text of Dr Destrée’s report will be published shortly by the Belgian Government.

No comments:

Post a Comment