https://ospreypublishing.com/thisweekhistory/

Though the uprising never ensued, the relative ease with which the communist forces penetrated to the center of US control in South Vietnam forever altered the perception of the war in the US. Due in part to the extensive media coverage of the battle, the US largely viewed the ‘great victory’ as a major defeat.

The following extract from Essential Histories 38: The Vietnam War 1956–1975 details General Pham Hung’s motivations for launching the Tet Offensive and provides a summary of the conflict and its aftermath.

The Tet Offensive

Partyzant Vietcongu, 1968 r. Wietnamka z ręcznym granatnikiem przeciwpancernym w ataku na bazę amerykańską, luty 1968 r. Żolnierze Vietcongu na amerykańskim czołgu pod Hue, początek lutego 1968 r.

Żołnierze amerykańskiej piechoty morskiej walczą o Cytadelę w Hue, 22 lutego 1968 r.

Żołnierze 2. Batalionu 5. Pułku Marines podczas walk w Hue, początek lutego 1968 r.

Further Reading

Campaign 4: Tet Offensive 1968 – Turning point in Vietnam details the plans and forces involved and explains how, despite the outcome of the battle, the American people and their leaders came to perceive the war for Vietnam as lost.

Essential Histories 38: The Vietnam War 1956–1975 provides a full account of the Vietnam War, including background information, battle accounts, and firsthand accounts from those involved in the conflict.

Campaign 150: Khe Sanh 1967–68 (available May 2005) details the siege and explains how, although the NVA successfully overran a Special Forces camp nearby, it was unable to drive US forces from Khe Sanh.

Warrior 98: US Army Infantryman in Vietnam 1965–73 (available May 2005) examines the training, acceptance and initial introduction to Vietnam’s varied conditions of service, while also detailing developments in weaponry, clothing and equipment.

Though the uprising never ensued, the relative ease with which the communist forces penetrated to the center of US control in South Vietnam forever altered the perception of the war in the US. Due in part to the extensive media coverage of the battle, the US largely viewed the ‘great victory’ as a major defeat.

The following extract from Essential Histories 38: The Vietnam War 1956–1975 details General Pham Hung’s motivations for launching the Tet Offensive and provides a summary of the conflict and its aftermath.

The Tet Offensive

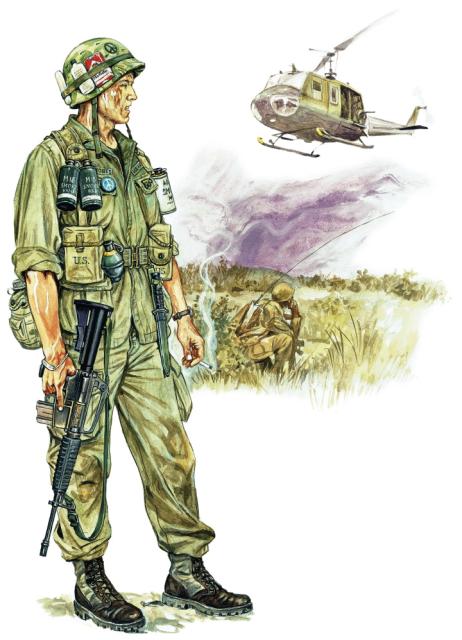

Amerykański szeregowiec z 1. Dywizji Kawalerii Powietrznej w hełmie M1 z pokrowcem maskującym, uzbrojony w karabin XM-177 Commando (krótsza wersja M-16), trzy granaty dymne M-18 i jeden zaczepny M-26 oraz bagnet M-3

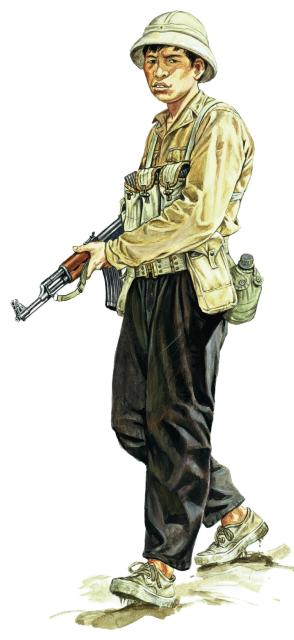

Żołnierz Vietcongu z pistoletem maszynowym AK 47 „Kałasznikow” ≥Schwytany Wietnamczyk brutalnie przesłuchiwany przez Amerykanów, 1967 r.

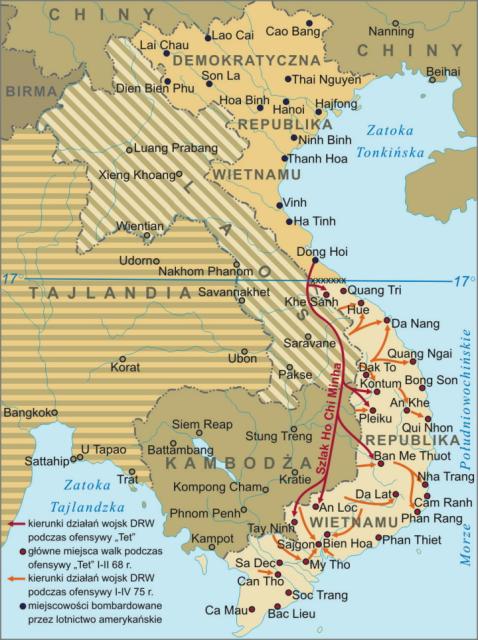

General Pham Hung developed the Tet Offensive as a three-phase plan. In preparation for this massive attack the Viet Cong had, in late 1967, lured US forces into the Vietnamese hinterlands, through a series of attacks and buildups, including the assault on Dak To and the concentration of forces around Khe Sanh. With American forces distant and distracted the Viet Cong began the dangerous task of gathering together a force of 84,000 near the major cities of South Vietnam. By January of 1968 the Viet Cong buildup was complete, and the communists stood ready for their offensive – simultaneous assaults on all of the major cities of South Vietnam, guarded by inferior ARVN opponents. The urban attacks were timed to take place during a ceasefire in celebration of the Tet Lunar New Year. Giap hoped that surprise would lead to initial victories before American troops could react and that seizure of only a few cities would result in the general uprising that would win the war.

Partyzant Vietcongu, 1968 r. Wietnamka z ręcznym granatnikiem przeciwpancernym w ataku na bazę amerykańską, luty 1968 r. Żolnierze Vietcongu na amerykańskim czołgu pod Hue, początek lutego 1968 r.

Żołnierze amerykańskiej piechoty morskiej walczą o Cytadelę w Hue, 22 lutego 1968 r.

Żołnierze 2. Batalionu 5. Pułku Marines podczas walk w Hue, początek lutego 1968 r.

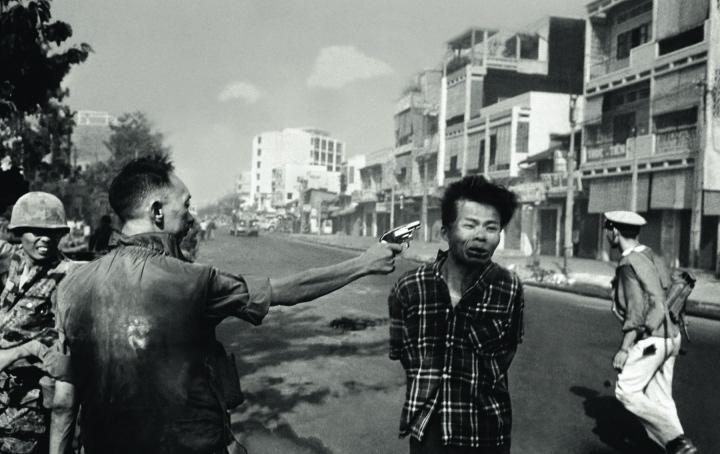

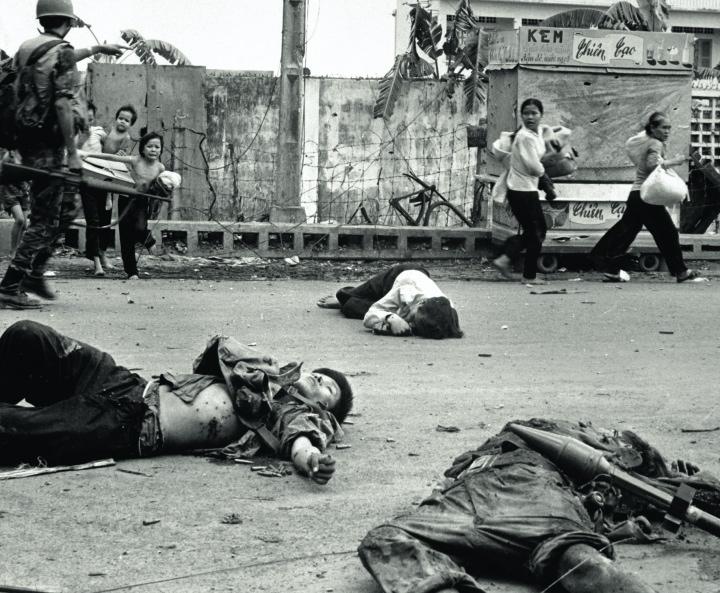

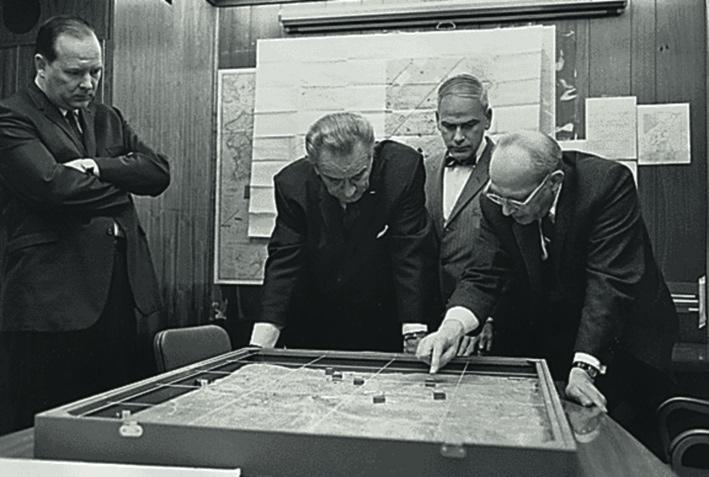

Generał południowowietnamskiej policji strzela w głowę schwytanemu dywersantowi Vietcongu, Sajgon, 1 lutego 1968 r. To zdjęcie wzburzyło amerykańską opinię publiczną i podważyło zaufanie do władz Wietnamu Pd. Zabici partyzanci Vietcongu na ulicy Sajgonu, 1968 r. Amerykańskie działo samobieżne podczas walk w Wietnamie, marzec 1968 r. Amerykanie walczą z partyzantami Vietcongu w Sajgonie, 31 stycznia 1968 r. Reporter stacji CBS Walter Cronkite rozmawia z oficerem marines pod Hue, luty 1968 r. Ulica w Sajgonie po ataku Vietcongu, 31 stycznia 1968 r. Prezydent Johnson podczas narady poświęconej sytuacji w Wietnamie, luty 1968 r.Uszkodzona fasada Ambasady USA w Sajgonie po ataku Vietcongu, 31 stycznia 1968 r. Żołnierze armii południowowietnamskiej podczas walk w Sajgonie, luty 1968 r.

Early on the morning of 30 January 1968 Viet Cong and NVA forces launched the Tet Offensive. The main focal point of the attack was Saigon, involving 35 battalions under the command of General Tran Van Tra. Communist forces did not attack in an organized effort to overthrow Saigon, rather they chose to strike out at targets of political and military importance in an effort to paralyze government control of the city and spur the hoped for general uprising. Toward this end specialist units struck at the Presidential Palace, the radio station and both the MACV and the ARVN headquarters. Most importantly, though, 19 men from the Viet Cong C-10 Sapper Battalion attacked the US embassy compound, prompting a six-hour battle with US military police. The Viet Cong sappers all perished without penetrating the embassy proper. However, the US media covered the attack extensively. Though the attack had failed, communist forces had penetrated to the very heart of American power in South Vietnam, indicating that the war there was much more serious than expected and that US boasts of imminent victory were misguided at best, and calculated lies at worst.

Across Saigon the Viet Cong used surprise to make initial gains, but failed in their overall objectives due to a quick reaction by powerful US and ARVN forces. Fighting was especially strong at the critical Tan Son Nhut airbase. Three VC battalions struck the facility surprising the American defenders and resulting in a hand-to-hand struggle that raged across the airfield and many of its buildings. With the aid of a relief column from the 25th Infantry based near Cu Chi the defenders eventually repulsed the VC attack with heavy losses. It was the same across most of the city; exposed VC forces were massacred at the hands of US and ARVN firepower, and the offensive collapsed in a matter of days. Even more important, though, the population had failed to rise up in support of the communists. It seemed that the great Tet gamble had failed.

The Tet Offensive as a whole followed a similar ebb and flow to the fighting in Saigon, except in the city of Hue. The home of the old imperial capital, Hue is divided into two sections by the Perfume River. The new city is south of the river, while north of the river lies the walled Citadel. On 31 January nearly 8,000 men of the 4th and 6th NVA regiments invaded Hue and quickly seized most of the Citadel and much of the new city as well. In the northern corner of the Citadel remnants of the 1st ARVN Division held out, and in the new city some 200 Americans and Australians held firm in the MACV compound. Demonstrating its surprise the Marine command at Phu Bai, only a few miles to the south, initially sent a single company to restore the situation. As the scale of the disaster dawned on the Americans, though, more and more troops were dedicated to the battle in Hue and in an effort to cut off communist supply lines to the city.

At first US and ARVN forces made scant progress against an enemy who had finally chosen to stand and fight, though they had relieved the beleaguered defenders of the MACV compound. Fighting in the winding, narrow confines of Hue’s streets negated the allied edges in mobility and firepower. It was not until 11 February, when the ARVN gave the go ahead for the use of heavy weaponry in the city that significant progress began to be made. By 9 February US Marines had cleared most of the new city, but the fighting in the Citadel, handled mainly by the ARVN, raged on, in many ways resembling the fighting in Stalingrad in the Second World War, as soldiers fought hand-to-hand for every square foot amid the rubble. The fighting for the Citadel raged until 24 February when ARVN Major Pham Van Dinh once again hoisted the South Vietnamese flag signifying victory.

During the struggle in Hue the communists had been able to implement their societal revolution unchecked for nearly an entire month. Terror ruled as VC and NVA soldiers combed the residential districts for supporters of the South Vietnamese regime. Estimates vary but communist forces rounded up and killed between 3,000 and 6,000 civilians. In the fighting across the city many more perished: US forces lost 216 dead, ARVN forces lost 384, NVA and VC forces lost 5,000. More than 1,000 civilians perished in the fighting and over 50 percent of the city was destroyed, leaving 116,000 homeless people from a total population of only 140,000. The civilian losses at the hands of the communists held even greater significance, foreshadowing the consequences of a communist victory. If US forces exited South Vietnam too quickly it seemed that the communists would unleash a societal holocaust upon supporters of the South Vietnamese regime, possibly slaughtering millions.

The final stage of Giap’s plan for the Tet Offensive involved an attack on the American Marine base at Khe Sanh after gathering some 40,000 troops to oppose the 6,000 marines that defended Khe Sanh and four surrounding hills. Westmoreland had expected such an attack and was ready when on 20 January the siege of Khe Sanh began. Giap hoped that his forces, which had cut off ground communication with Khe Sanh, could cripple the airstrip there and that artillery fire could pound the Marines into submission. In addition NVA forces launched infantry attacks on more isolated US outposts and eventually seized Hill 861 and Lang Vei Special Forces Camp. As the noose tightened around the beleaguered Marines, Westmoreland launched a planned counterstrike and unleashed Operation Niagra against the concentrated NVA forces. American fighter-bombers and B-52s struck communist positions around the clock. During a period of the most concentrated bombing in the history of warfare US air forces dropped bomb tonnage equivalent to 10 Hiroshima-sized atomic bombs.

At the end of February, heralded by their heaviest artillery barrage of the war, the 304th NVA Regiment launched a human wave assault on Khe Sanh, but it was obliterated by heavy US firepower. Though the outcome was no longer in doubt fighting continued at Khe Sanh until 8 April, when the arrival of ground units lifted the 77-day siege. Giap was denied his great victory as the Marines had held out against heavy odds, supplied by air from an airstrip that remained operational for the entire length of the siege. US and ARVN forces lost some 400 dead during the siege, but the constant pounding of Operation Niagra had inflicted an estimated 12,000 dead upon the communist forces, making the siege of Khe Sanh a resounding victory for American force of arms.

The Tet Offensive and its attendant attack on Khe Sanh had been a total failure for the communists. Of the 84,000 troops committed to Tet, nearly 58,000 had been killed, almost wiping out the Viet Cong as an effective fighting force. The scale of the disaster compelled the remaining VC cadres to retreat into the Vietnamese hinterlands to regroup, in the process abandoning land that had been under Viet Cong control for years. From this point, due to the demise of the Viet Cong the war became more conventional, and was controlled more directly from Hanoi. Also the Communists had expected that the ARVN would crumble, but it had fought hard and well, indicating that South Vietnam was coming of age and was something more than a lackey state of the US. Tet had been an ill-advised, demoralizing, controversial, comprehensive defeat but surprisingly it would also turn the tide of the war in favour of the communists.

Further Reading

Campaign 4: Tet Offensive 1968 – Turning point in Vietnam details the plans and forces involved and explains how, despite the outcome of the battle, the American people and their leaders came to perceive the war for Vietnam as lost.

Essential Histories 38: The Vietnam War 1956–1975 provides a full account of the Vietnam War, including background information, battle accounts, and firsthand accounts from those involved in the conflict.

Campaign 150: Khe Sanh 1967–68 (available May 2005) details the siege and explains how, although the NVA successfully overran a Special Forces camp nearby, it was unable to drive US forces from Khe Sanh.

Warrior 98: US Army Infantryman in Vietnam 1965–73 (available May 2005) examines the training, acceptance and initial introduction to Vietnam’s varied conditions of service, while also detailing developments in weaponry, clothing and equipment.

No comments:

Post a Comment