Francuska szabla lekkiej kawaleri AN IX

Francuski karabin Corriege AN IX, wersja dragońska

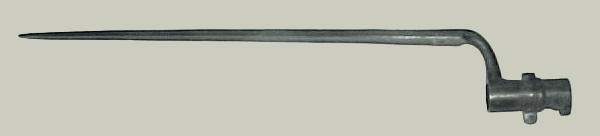

Bagnet do karabinu Corriege AN IX

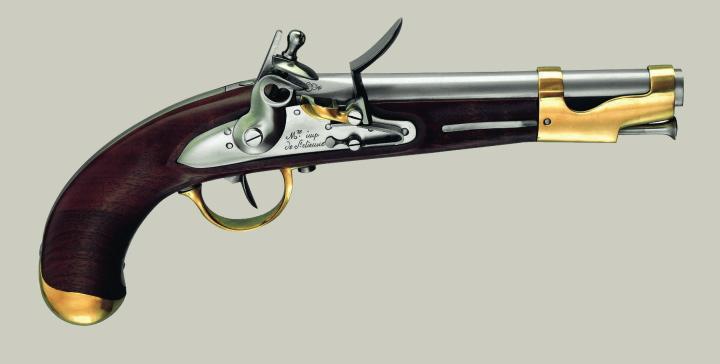

Francuski pistolet AN IX

Żelazny książę - Arthur Wellesley, książę Wellington (1769 - 1852)

Campaign 48: Salamanca details all aspects of the Peninsular War’s most decisive battle, including the opposing forces, commanders, aftermath and the battlefield today. It includes the following dramatic account of Wellington’s resistance of the French counterattack:

The repulse of the 4th Division and Pack’s brigade left a yawning gap in the centre of Wellington’s position, and despite the hammering the French had taken elsewhere on the battlefield, Clausel (now in command following successive wounds to Marmont and Bonnet) was presented with the opportunity to salvage something from the wreckage of the day’s fighting, perhaps even a French victory. It was certainly a critical point in the battle. Clausel decided to grasp the opportunity with both hands and go for victory, even though behind him Leith and Pakenham were driving everything before them. Having decided upon this bold course of action Clausel threw his division into the gap, supported by three of Bonnet’s regiments and by three regiments of Boyer’s dragoons.

The ground to the west of the Greater Arapil was soon covered with the dark, dusty masses of Frenchmen launched by Clausel to save the day. In front of them Cole’s division reeled backwards towards the Lesser Arapil, while Pack’s broken brigade streamed away behind them. Ellis’s brigade was pushed back, almost to the Lesser Arapil, while Stubbs’s brigade, alongside it, was forced to form a square in order to protect itself from French dragoons who nevertheless got in among some of them. In fact, some French cavalry swept round and got as far as the 6th Division, Wellington’s reserve line, which had been brought forward to support the 4th Division.

Clausel’s counterattack represented the last, desperate attempt to salvage something from the day’s fighting, if not victory itself. But, as so often in his career, Wellington demonstrated his unerring powers of foresight and at 5.30pm brought forward Clinton’s 6th Division, who were fresh and yet to be involved in any of the day’s fighting. Clausel’s division was attacked not only frontally by Clinton, but also by Spry’s Portuguese brigade which Marshal Beresford detached from the 5th Division and led diagonally against Clausel’s left flank. Beresford, in fact, was wounded during this attack which halted Clausel’s division.

Clinton’s 6th Division, meanwhile, continued its advance, with Hinde’s brigade on the right and Hulse’s on the left, and Rezonde’s Portuguese in the second line, their long lines overlapping both ends of Clausel’s division. Bonnet’s three regiments soon found themselves engaged against a superior firing line and were thrown back upon the main body of Clausel’s division, having suffered casualties of around 500 men each. Bonnet’s reverse exposed the right flank of Clausel’s division and forced it to retreat too. Seizing his opportunity, Wellington directed the 1st Division, still as yet inactive save for the light companies of the Guards, to drive a wedge between Foy and the Greater Arapil, a move which if successful would cut off Foy from the main body of the French army. In the event, Gen. Campbell, commanding the 1st Division, pushed forward only his skirmishers of the King’s German Legion, who hardly constituted a real threat to a veteran like Foy. Their advance was, nevertheless, enough to convince the three battalions of the French 120th Regiment, still occupying the summit of the Greater Arapil, that retreat was the better part of valour and they scrambled down the sides of the hill to rejoin the great body of fugitives now streaming away to the south-east, their flank coming under fire from Campbell’s Germans as they did so.

With Clausel’s courageous counterattack a failure, the battle of Salamanca entered its closing stages. Foy’s division was moving slowly but cautiously round the back of the Greater Arapil, threatened all the time by the 1st and Light Divisions; Sarrut’s division was heavily engaged trying to stem the relentless advance of the 3rd and 5th Divisions, while Ferey’s division clung to the top of a ridge to the south-east of the Greater Arapil. Ferey, in fact, constituted the last line of French resistance as the rest of the French army fell back towards him. Beyond the dark masses of fleeing Frenchmen could be seen clouds of dust through which burst Wellington’s triumphant divisions. Away to the west the 3rd and 5th Division drove forward with Bradford’s Portuguese and the 7th Division on their left. Squadrons of British and Portuguese cavalry hovered, gathering up surrendering enemy infantrymen and sabring any that resisted. Beyond the Greater Arapil the 1st and Light Divisions advanced, but the main and more immediate threat to the French came from Clinton’s advancing 6th Division.

Ferey had been forewarned by Clausel that his division was expected to cover the retreat and the acting commander-in-chief was not to be let down. Ferey was aided considerably by a fairly steep ridge which allowed those at the rear to fire over the heads of those in front, and so more firepower could be brought against the oncoming 6th Division of Wellington’s army. Ferey formed seven of his battalions into line with a single square on each flank and when Clinton’s men got to within 200 yards of the French position Ferey gave the order to open fire. Scores of dusty red-coated British infantrymen fell as the weight of fire from seven battalions of enemy infantry crashed into them. Clinton’s men halted to load and fire and the two sides began a deadly duel of musketry, comparable to that at Albuera, both sides trading volleys for the best part of an hour.

As the light began to fade, the spectacle was made all the more dramatic as the scene was illuminated by scrub fires kindled by burning cartridge papers. The scene itself resembled that at Albuera, and so too did the outcome, for it was the French who eventually broke, the power of Wellington’s infantry once again winning the day, but at a price. Indeed, as Ferey’s infantry fell back, it was left to the Portuguese to complete the job, the men of the 6th Division having suffered severe casualties. British artillery also joined in to keep Ferey’s men on the move and it was a round shot from one of these guns which cut Ferey in two, a sad end for a brave soldier who had inflicted heavy casualties on Clinton’s division. Indeed, even with Ferey gone his men continued to put up a gallant fight. They successfully drove back Rezende’s Portuguese brigade and it was not until the advancing 5th Division came upon the scene that the final blow was dealt by Wellington’s men.

Leith’s troops fell upon the left flank of the French, sending the French 70th Regiment into a state of sheer panic. The French army had been making a fighting retreat until that moment, but when the 70th broke and fled, panic spread throughout their ranks and soon almost the whole of the French army was in full flight heading towards the great forest which lay to the south-east of the battlefield. Only the French 31st Light stuck to their task, fighting as they went while chaos reigned all around them. Foy’s division fell back in an orderly manner too, shadowed closely by the 1st and Light Divisions, until it too reached the safety of the forest.

Elite 83: Napoleon’s Commanders (2) c.1809–15 covers the careers and personalities of over 20 of Napoleon’s leading commanders, including the much-criticized marshal Marmont:

Of all the marshals, Marmont became the least popular among his own countrymen. Belonging to the minor nobility, he was commissioned from the Châlons artillery school in 1792; he met his fellow-gunner Napoleon at Toulon, and they became firm friends. Marmont served as Napoleon’s ADC in Italy and was appointed général de brigade after capturing the banner of the Knights of St John at Malta. He returned from Egypt with Napoleon; assisted in the coup of Brumaire; and commanded the artillery at Marengo with very conspicuous success, contributing notably to that victory. Général de division from September 1800, as Inspector-General of Artillery he introduced important reforms (including the An XIII system of ordnance), and in 1805 led II, later I Corps. From July 1806 he was governor-general and military commander of Dalmatia, where he had considerable success both in consolidating Napoleon’s hold on the territory and in improving conditions for the inhabitants; it was from Ragusa, now Dubrovnik, that he took his title of Duc de Raguse. In 1809 he commanded XI Corps, but although he received his marshal’s baton that July, Napoleon confessed that it had been awarded more from friendship than for outstanding military merit.

In 1811 Marmont went to the Peninsula and took command of the Army of Portugal; but although he manoeuvred competently against Wellington, he was massively defeated at Salamanca (though he claimed that things only began to go wrong after he was wounded by a shell). In 1813 he returned to service and led VI Corps at Lützen, Bautzen, Dresden and Leipzig, but he aroused Napoleon’s anger in 1814 when he was beaten at Laon. Much worse was to follow when he negotiated a truce which permitted the Allies to enter Paris, arousing the absolute hatred of most of his countrymen. (His old enemy Wellington was more pragmatic, stating that ‘the French marshals and troops … all began to treat, and Marmont being the nearest to Paris, treated first. That was all.’)

Although Marmont was honoured by the Bourbons, even they declined to trust him, and he held no further field command; he was forced into exile with Charles X in 1830, and never returned to France. He settled in Vienna, wrote widely on travel, military and historical matters, and – somewhat ironically – became tutor to the Duke of Reichstadt, Napoleon’s only legitimate son, who was being raised by his mother’s Austrian kinfolk. Although he was not untalented militarily, Marmont’s genuine merits have tended to be obscured by his reputation for betrayal.

Further Reading

Essential Histories Specials 4: The Napoleonic Wars – The rise and fall of an empire not only places the battle of Salamanca in the context of the Peninsular War but also in the wider context of the bloody Napoleonic era.

Battle Orders 2: Wellington’s Army in the Peninsulaprovides a clear account of how the British Army was organized, who commanded it, and how it functioned in the field during the Peninsular War.

For more information on the uniforms, equipment, history and organization of the British, Portuguese and Spanish troops that fought in the Peninsular War see:

Men-at-Arms 382: Wellington’s Peninsula Regiments (1) The Irish

Men-at-Arms 400:Wellington’s Peninsula Regiments (2) The Light Infantry

Men-at-Arms 343:The Portuguese Army of the Napoleonic Wars (1)

Men-at-Arms 346: The Portuguese Army of the Napoleonic Wars (2)

Men-at-Arms 358: The Portuguese Army of the Napoleonic Wars (3)

Men-at-Arms 321: Spanish Armies of the Napoleonic Wars (1) 1793–1808

Men-at-Arms 332: Spanish Armies of the Napoleonic Wars (2) 1808–12

For more information on the French troops of the Napoleonic Wars see:

Men-at-Arms 141: Napoleon’s Line Infantry

Men-at-Arms 146: Napoleon’s Light Infantry

Warrior 57: French Napoleonic Infantryman

No comments:

Post a Comment