https://ospreypublishing.com/thisweekhistory/

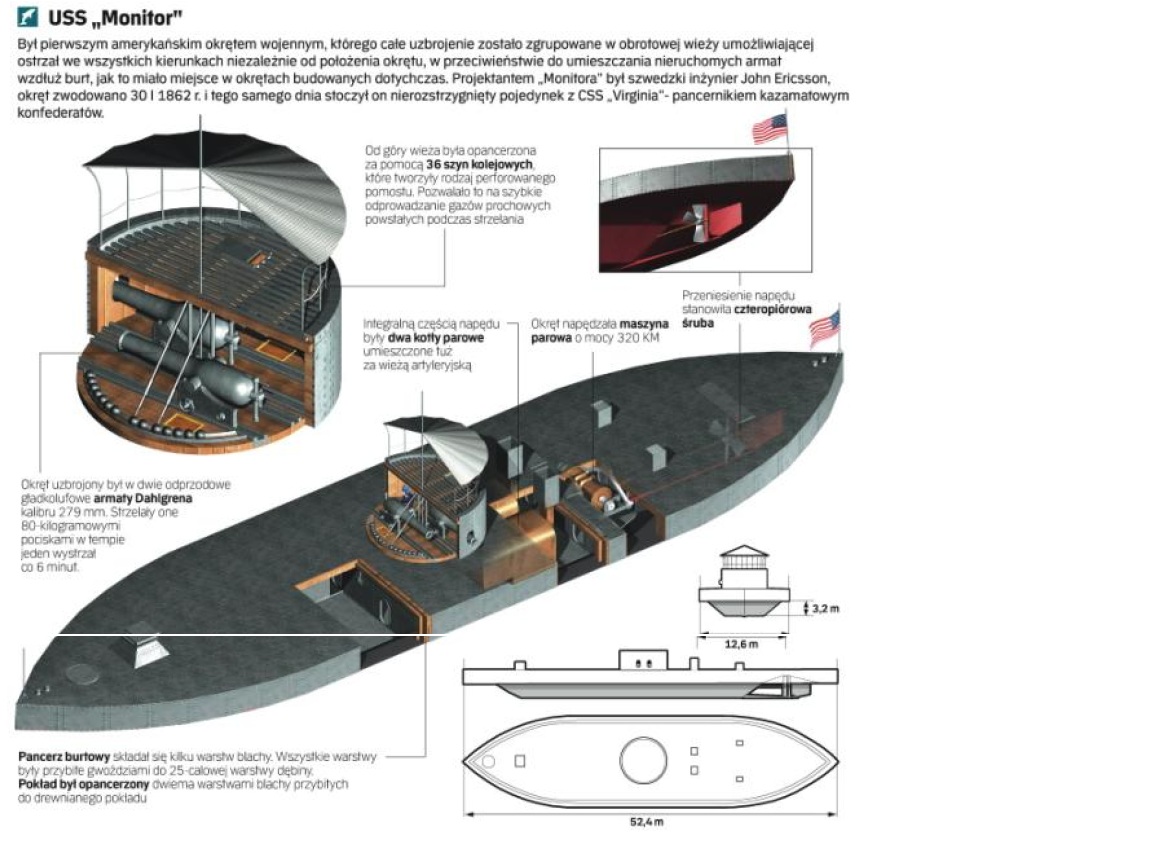

USS „Monitor”

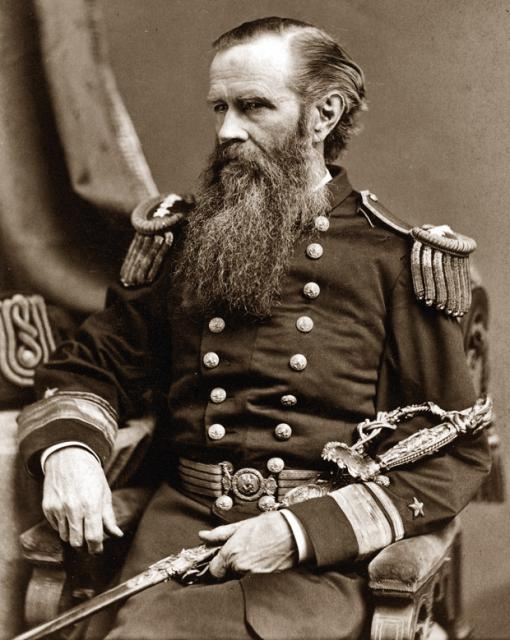

Kpt. John Lorimer Worden, dowódca USS „Monitor”

Admirał marynarki konfederacji Franklin Buchanan, były dowódca CSS „Virginia”

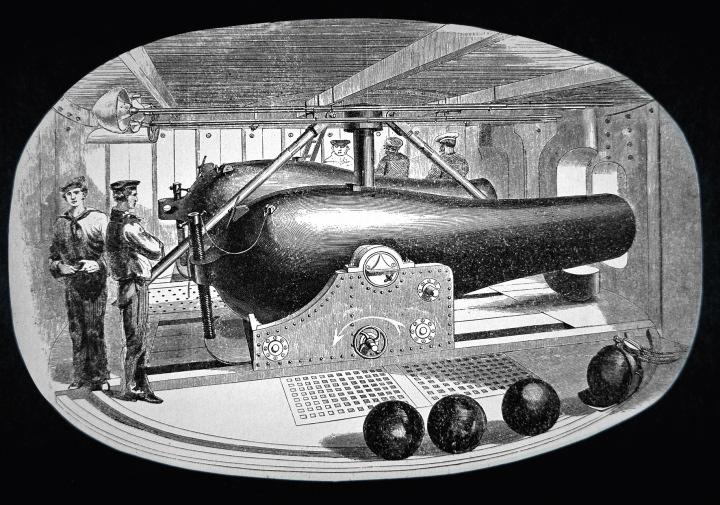

Dwa gładkolufowe działa kal. 280 mm w obrotowej wieży USS „Monitor”, rycina z epoki

Kepi artylerzysty US „Navy” z czasów wojny secesyjnej

Kurtka mundurowa podporucznika marynarki Unii

The Ironclads USS Monitor and the CSS Virginia met on 9 March. As battles go, Hampton Roads was inconclusive: it was a four hour duel that left neither side victorious. By the battle’s end, the Monitor had been hit 23 times, the Virginia 20 times. Neither ship was badly damaged, and only one man wounded.

Despite this seeming stalemate, the importance of this battle both in the context of the American Civil War, and in the history of naval warfare cannot be denied. The previous day the Virginia destroyed two powerful warships and killed or wounded hundreds of Union soldiers, but the next day the Monitor countered the threat caused by the Virginia, crushing Confederate hopes of breaking the Union blockade. In the history of naval warfare, the first day of the battle demonstrated the vulnerability of wooden ships, but the second day ushered in the alternative, the ironclad.

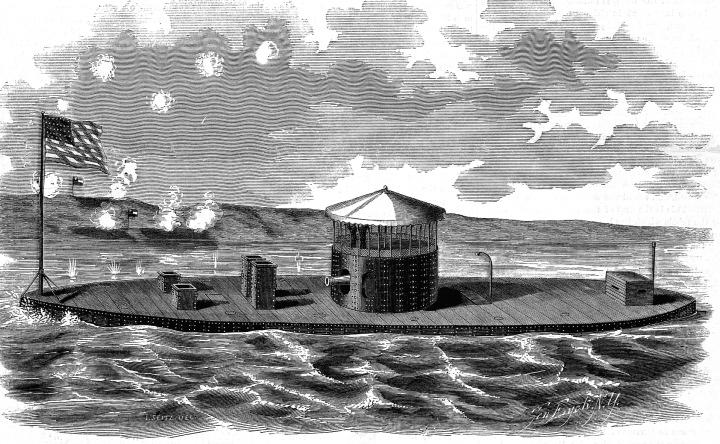

Hampton Roads was also probably one of the strangest spectacles ever seen. Not only because the onlookers watched for four hours as the two vessels pounded at each other with apparently no effect, but also because both ships looked extraordinary. The Virginia was said to resemble an upturned bathtub, and the Monitor even more oddly, has been described as an immense shingle floating on the water, with a gigantic cheesebox rising from its centre; no sails, no wheels, no smokestacks, no guns.

Further reading

The Duel of the Ironclads (extracts below), traces the development of the American Civil War ironclad and, in particular, of the two revolutionary warships that clashed at Hampton Roads, and gives a vivid account of the battle. This material is also available in separate volumes: New Vanguard 41: Confederate Ironclad 1861–65, New Vanguard 45: Union Monitor 1861–65 and Campaign 103: Hampton Roads 1862, Clash of the Ironclads.

New Vanguard 49: Mississippi River Gunboats of the American Civil War 1861–65 and New Vanguard 56: Union River Ironclad 1861–65 deal with the gunboats and ironclads that fought for domination of the great rivers of North America.

New Vanguard 64: Confederate Raider 1861–65 looks at a different Confederate response to Union naval superiority, commerce raiding on the high seas.

Essential Histories 4: The American Civil War (1) The war in the East 1861-May 1863 places naval operations on the east coast in the context of the first half of the war in that theatre, and combines with Essential Histories 5: The American Civil War (3) The war in the East 1863 -1865, Essential Histories 10: The American Civil War (2) The war in the West 1861-July 1863 and Essential Histories 11: The American Civil War (4) The war in the West 1863 -1865 to provide a complete history of this immense conflict.

Extracts from Duel of the Ironclads

The battle in context

The battle of Hampton Roads on 9 March 1862 saw the first ever clash between two ironclad warships. The day before, the USS Virginia (sometimes referred to incorrectly as the Merrimac or Merrimack) had demonstrated the effectiveness of ironclad warships against wooden vessels. In a singularly one-sided engagement, its guns destroyed two wooden warships, lying at anchor off Newport News, Virginia. Although these warships fought back with vigour, their shot proved singularly ineffective against the armour-plated casemate of the Virginia. Shot bounced off, and the only real damage was the denting of its plating and the peppering of its smokestack. By contrast its explosive shells tore through the wooden sides of the Cumberland, and caused incredible slaughter amongst its gun crews. The Virginia was a revolutionary warship in one other aspect. During its attack on the USS Cumberland, it rammed the wooden sloop using a purpose-built heavy cast-iron ram fitted to its bow. The collision ripped a hole in the side of the Union warship “wide enough to let in a horse and cart”. Although the ramming attempt was a success, it also damaged the Virginia, and the ironclad was almost pulled under by the Cumberland before it shook itself free. It continued to pour shot into the hull of the stricken Union warship as it backed off, then turned away in search of a new victim. The USS Congress was virtually destroyed when the Virginia steamed past it at point-blank range, its guns blazing. The cumbersome ironclad then headed upriver to turn around, then returned to finish the job. By the end of the action both Union warships were shattered and sinking, and the rest of the wooden-hulled blockading fleet off Hampton Roads lay at the mercy of the Confederate leviathan. If any naval officer still doubted the effectiveness of shell-guns against wooden warships, or the defensive capabilities of ironclads, these doubts had been dispelled in a single day.

The catastrophe would have been complete if it were not for the Union Navy’s own ironclad, which spent the day of the battle steaming south from New York to Hampton Roads. This frail-looking little craft (described by observers as a “cheesebox on a raft”) would not only stop any further depredations by the Confederate warship, but it would restore the strategic balance. Many historians regarded the Battle of Hampton Roads as inconclusive. After all, neither the USS Monitor nor the CSS Virginia who fought their duel on 9 March 1862 inflicted more than minor damage on their opponent. Neither ship was able to gain a significant tactical advantage over the other, and the hard-fought battle petered out when the constraints of ammunition supply and tidal conditions forced an end to the fighting. No fatalities were caused on either side. To take this view is to ignore the incredibly far-reaching impact of the battle.

When it steamed into Hampton Roads on the morning of 9 March, the CSS Virginia was prepared to finish the destruction of the Union blockading fleet, a task it had only partially accomplished the day before. Its first victim was going to be the wooden steam frigate USS Minnesota, which had run aground during the previous day. Like a sacrificial lamb tied to the altar, it could do nothing to avert its fate. The warship and its crew were saved by the intervention of the Monitor, initiating one of the strangest naval encounters in history. The battle between the Monitor and the Virginia was witnessed by thousands of soldiers, sailors and civilians who lined both sides of Hampton Roads. Few of these spectators were in any doubt that what they were watching was history in the making; the first clash between two revolutionary new warships. The two ironclads appeared as different from each other as it was possible to be. The Virginia had been built using the lower hull of the USS Merrimac, and its profile underwater was the same as the former steam frigate. On top of this long, narrow hull, the designers constructed an armored box, a wooden framework covered in two layers of iron plating. Looking like a large upturned bath, this “casemate” was pierced with gunports, allowing the deployment of the Virginia’s main armament of newly-built rifled guns. These were arranged to fire out of fixed positions to each side, while 7-inch rifled pieces in the bow and stern gave the ironclad some degree of all-round firepower.

In complete contrast, the USS Monitor was 90 feet shorter than its opponent, and the freeboard of its flat iron deck was so low that the vessel’s decks were practically awash. This had almost led to the foundering of the ironclad during its long voyage south, and would play a contributory part in its sinking off Cape Hatteras just ten months later. Its profile was dominated by its iron turret; inside which were two large smoothbore guns. Unlike the Virginia, whose guns were aimed by turning the hull, the Monitor’s turret design was truly revolutionary, permitting the guns to fire in virtually any direction, regardless of which way the ship was heading at the time. What followed would be as much a test of the two doctrines of ironclad construction as a battle between the vessels themselves.

The battle of Hampton Roads was a dramatic demonstration in the defensive strengths of both ironclad designs. For various reasons, shot from the guns of the Virginia and the Monitor were unable to penetrate the armor of their opponents’ ship. While these faults were later rectified, the overall impression of the battle was that ironclads were proof against anything an enemy ship could throw at it. In a single day, wooden warships had been rendered obsolete, and the age of armored fighting ships had begun. As the editor of the Norfolk Day Book wrote the evening after the battle; “this successful and terrible work will create a revolution in naval warfare, and henceforth iron will be king of the seas”. The first tentative steps of this great naval revolution had been made.

The duel commences

When the two were within 100 yards of each other, Worden turned the Monitor so its bows faced upstream, taking the way off the ship. He then gave the order to open fire. Greene decided to fire the first shot himself. “I triced up the port, ran out the gun, and taking deliberate aim, pulled the lockstring.” The Monitor shuddered under the impact. Observers thought the first shot hit the Virginia “plumb on the waterline.” Jones was in the process of turning his ship to starboard, which presented his full broadside to the enemy. Both ships were now parallel to each other, but headed in opposite directions; the Monitor facing west and the Virginia east. He gave the order to fire. According to Greene, it was “a rattling broadside … the turret and other parts of the ship were heavily struck, but the shots did not penetrate; the tower was intact, and it continued to revolve.”

Greene later wrote that “a look of confidence passed over the men’s faces, and we believed the Merrimack would not repeat the work it had accomplished the day before.” One gunner even thought the Confederates were firing canister at them, as the shots “rattled on our iron decks like hailstones.”

Worden recalled that “at this period I felt some anxiety about the turret machinery, it having been predicted by many persons that a heavy shot with great initial velocity striking the turret would so derange it as to stop its working; but finding that it had been twice struck and still revolved as freely as ever, I turned back with renewed confidence and hope, and continued the engagement at close quarters; every shot from our guns taking effect on the high sides of our adversary, stripping off the iron freely.” This was the ultimate test of Ericsson’s invention. Both the Monitor’s hull and turret armor were proof to the rifled shot fired by its opponent. Worden “passed slowly by it, within a few yards, delivering fire as rapidly as possible and receiving from it a rapid fire in return, both from its great guns and musketry – the latter aimed at the pilot house, hoping undoubtedly to penetrate through the lookout holes and to disable the commanding officer and the helmsman.”

Although the Virginia maintained a heavy fire, its shot seemed to be incapable of damaging the Monitor. Officers in the attendant flotilla of Confederate vessels near Sewell’s Point were heard to say “the unknown craft was a wicked thing, and that we better not get too near it.” It was becoming increasingly apparent that the Virginia had met its match.

A battle of maneuver

After two hours of dueling, both captains were beginning to realize that they had little chance of damaging their opponent through gunfire alone. While Jones had the option of trying to maneuver closer to the Minnesota to attack it, both captains could also try to ram their opponent. The duel continued, but instead of a contest between two ships steaming in circles around each other, around 11.00am Jones and Worden began to try other stratagems. Of the two ships, the Monitor was by far the more maneuverable, and Worden decided to try to ram the stern of its opponent, hoping to damage its screw (propeller) or rudder. If the Virginia could be disabled, then the Monitor could find a blind spot and pour fire into it without danger. First, Worden had to deal with a logistical problem. His guns had run out of ammunition, and in order to replenish the supplies within the turret, he had to disengage, and steam away from his opponent. Shot was brought up out of the hold, and while this was going on, Jones edged his ship closer to the Minnesota. Both he and his pilot were unsure of how deep the water was beneath their keel, and by the time they had charted a course to get as close to the wooden frigate as they could, the Monitor was steaming back into the fray. Worden made a dash for the Virginia’s stern, but missed by just two feet. Jones also decided to break the circling pattern adopted by the two ships in an attempt to attack the Minnesota. He steered northwest, forcing the Monitor to chase after him, and try to cut in between the Virginia and the stranded frigate. Just at that moment, in Lieutenant Jones’s words, “In spite of all the cares of our pilots, we ran ashore”. The surgeon, Dr. Phillips, was less reluctant to place blame: “the pilot purposely ran us aground nearly two miles off from the Minnesota, fearing that frigate’s terrible broadside.” This was a potential disaster for the Confederates, and Worden was quick to take advantage of their plight. He laid his ship alongside the Virginia so that the smaller ironclad lay beneath the muzzles of the Confederate guns. As Van Brunt described it; “the contrast was that of a pygmy to a giant.” Phillips recalled that “it directed a succession of shots at the same section of our vessel, and some of them striking close together, started the timbers and drove them perceptibly in … it began to sound every chink in our armor – every one but that which was actually vulnerable, had it known it.” He was referring to the waterline. As the Virginia burned coal, it became lighter, and consequently its protective knuckle at the bottom of the casemate rose closer to the surface. It was designed to extend almost three feet below the waterline. After two days of fighting, it was only six inches below the surface. As Ramsay reported: “Lightened as we were, these exposed portions rendered us no longer an ironclad, and the Monitor might have pierced us between wind and water had it depressed its gun.”

USS „Monitor”

Kpt. John Lorimer Worden, dowódca USS „Monitor”

Admirał marynarki konfederacji Franklin Buchanan, były dowódca CSS „Virginia”

Dwa gładkolufowe działa kal. 280 mm w obrotowej wieży USS „Monitor”, rycina z epoki

Kepi artylerzysty US „Navy” z czasów wojny secesyjnej

Kurtka mundurowa podporucznika marynarki Unii

The Ironclads USS Monitor and the CSS Virginia met on 9 March. As battles go, Hampton Roads was inconclusive: it was a four hour duel that left neither side victorious. By the battle’s end, the Monitor had been hit 23 times, the Virginia 20 times. Neither ship was badly damaged, and only one man wounded.

Despite this seeming stalemate, the importance of this battle both in the context of the American Civil War, and in the history of naval warfare cannot be denied. The previous day the Virginia destroyed two powerful warships and killed or wounded hundreds of Union soldiers, but the next day the Monitor countered the threat caused by the Virginia, crushing Confederate hopes of breaking the Union blockade. In the history of naval warfare, the first day of the battle demonstrated the vulnerability of wooden ships, but the second day ushered in the alternative, the ironclad.

Hampton Roads was also probably one of the strangest spectacles ever seen. Not only because the onlookers watched for four hours as the two vessels pounded at each other with apparently no effect, but also because both ships looked extraordinary. The Virginia was said to resemble an upturned bathtub, and the Monitor even more oddly, has been described as an immense shingle floating on the water, with a gigantic cheesebox rising from its centre; no sails, no wheels, no smokestacks, no guns.

Further reading

The Duel of the Ironclads (extracts below), traces the development of the American Civil War ironclad and, in particular, of the two revolutionary warships that clashed at Hampton Roads, and gives a vivid account of the battle. This material is also available in separate volumes: New Vanguard 41: Confederate Ironclad 1861–65, New Vanguard 45: Union Monitor 1861–65 and Campaign 103: Hampton Roads 1862, Clash of the Ironclads.

New Vanguard 49: Mississippi River Gunboats of the American Civil War 1861–65 and New Vanguard 56: Union River Ironclad 1861–65 deal with the gunboats and ironclads that fought for domination of the great rivers of North America.

New Vanguard 64: Confederate Raider 1861–65 looks at a different Confederate response to Union naval superiority, commerce raiding on the high seas.

Essential Histories 4: The American Civil War (1) The war in the East 1861-May 1863 places naval operations on the east coast in the context of the first half of the war in that theatre, and combines with Essential Histories 5: The American Civil War (3) The war in the East 1863 -1865, Essential Histories 10: The American Civil War (2) The war in the West 1861-July 1863 and Essential Histories 11: The American Civil War (4) The war in the West 1863 -1865 to provide a complete history of this immense conflict.

Extracts from Duel of the Ironclads

The battle in context

The battle of Hampton Roads on 9 March 1862 saw the first ever clash between two ironclad warships. The day before, the USS Virginia (sometimes referred to incorrectly as the Merrimac or Merrimack) had demonstrated the effectiveness of ironclad warships against wooden vessels. In a singularly one-sided engagement, its guns destroyed two wooden warships, lying at anchor off Newport News, Virginia. Although these warships fought back with vigour, their shot proved singularly ineffective against the armour-plated casemate of the Virginia. Shot bounced off, and the only real damage was the denting of its plating and the peppering of its smokestack. By contrast its explosive shells tore through the wooden sides of the Cumberland, and caused incredible slaughter amongst its gun crews. The Virginia was a revolutionary warship in one other aspect. During its attack on the USS Cumberland, it rammed the wooden sloop using a purpose-built heavy cast-iron ram fitted to its bow. The collision ripped a hole in the side of the Union warship “wide enough to let in a horse and cart”. Although the ramming attempt was a success, it also damaged the Virginia, and the ironclad was almost pulled under by the Cumberland before it shook itself free. It continued to pour shot into the hull of the stricken Union warship as it backed off, then turned away in search of a new victim. The USS Congress was virtually destroyed when the Virginia steamed past it at point-blank range, its guns blazing. The cumbersome ironclad then headed upriver to turn around, then returned to finish the job. By the end of the action both Union warships were shattered and sinking, and the rest of the wooden-hulled blockading fleet off Hampton Roads lay at the mercy of the Confederate leviathan. If any naval officer still doubted the effectiveness of shell-guns against wooden warships, or the defensive capabilities of ironclads, these doubts had been dispelled in a single day.

The catastrophe would have been complete if it were not for the Union Navy’s own ironclad, which spent the day of the battle steaming south from New York to Hampton Roads. This frail-looking little craft (described by observers as a “cheesebox on a raft”) would not only stop any further depredations by the Confederate warship, but it would restore the strategic balance. Many historians regarded the Battle of Hampton Roads as inconclusive. After all, neither the USS Monitor nor the CSS Virginia who fought their duel on 9 March 1862 inflicted more than minor damage on their opponent. Neither ship was able to gain a significant tactical advantage over the other, and the hard-fought battle petered out when the constraints of ammunition supply and tidal conditions forced an end to the fighting. No fatalities were caused on either side. To take this view is to ignore the incredibly far-reaching impact of the battle.

When it steamed into Hampton Roads on the morning of 9 March, the CSS Virginia was prepared to finish the destruction of the Union blockading fleet, a task it had only partially accomplished the day before. Its first victim was going to be the wooden steam frigate USS Minnesota, which had run aground during the previous day. Like a sacrificial lamb tied to the altar, it could do nothing to avert its fate. The warship and its crew were saved by the intervention of the Monitor, initiating one of the strangest naval encounters in history. The battle between the Monitor and the Virginia was witnessed by thousands of soldiers, sailors and civilians who lined both sides of Hampton Roads. Few of these spectators were in any doubt that what they were watching was history in the making; the first clash between two revolutionary new warships. The two ironclads appeared as different from each other as it was possible to be. The Virginia had been built using the lower hull of the USS Merrimac, and its profile underwater was the same as the former steam frigate. On top of this long, narrow hull, the designers constructed an armored box, a wooden framework covered in two layers of iron plating. Looking like a large upturned bath, this “casemate” was pierced with gunports, allowing the deployment of the Virginia’s main armament of newly-built rifled guns. These were arranged to fire out of fixed positions to each side, while 7-inch rifled pieces in the bow and stern gave the ironclad some degree of all-round firepower.

In complete contrast, the USS Monitor was 90 feet shorter than its opponent, and the freeboard of its flat iron deck was so low that the vessel’s decks were practically awash. This had almost led to the foundering of the ironclad during its long voyage south, and would play a contributory part in its sinking off Cape Hatteras just ten months later. Its profile was dominated by its iron turret; inside which were two large smoothbore guns. Unlike the Virginia, whose guns were aimed by turning the hull, the Monitor’s turret design was truly revolutionary, permitting the guns to fire in virtually any direction, regardless of which way the ship was heading at the time. What followed would be as much a test of the two doctrines of ironclad construction as a battle between the vessels themselves.

The battle of Hampton Roads was a dramatic demonstration in the defensive strengths of both ironclad designs. For various reasons, shot from the guns of the Virginia and the Monitor were unable to penetrate the armor of their opponents’ ship. While these faults were later rectified, the overall impression of the battle was that ironclads were proof against anything an enemy ship could throw at it. In a single day, wooden warships had been rendered obsolete, and the age of armored fighting ships had begun. As the editor of the Norfolk Day Book wrote the evening after the battle; “this successful and terrible work will create a revolution in naval warfare, and henceforth iron will be king of the seas”. The first tentative steps of this great naval revolution had been made.

The duel commences

When the two were within 100 yards of each other, Worden turned the Monitor so its bows faced upstream, taking the way off the ship. He then gave the order to open fire. Greene decided to fire the first shot himself. “I triced up the port, ran out the gun, and taking deliberate aim, pulled the lockstring.” The Monitor shuddered under the impact. Observers thought the first shot hit the Virginia “plumb on the waterline.” Jones was in the process of turning his ship to starboard, which presented his full broadside to the enemy. Both ships were now parallel to each other, but headed in opposite directions; the Monitor facing west and the Virginia east. He gave the order to fire. According to Greene, it was “a rattling broadside … the turret and other parts of the ship were heavily struck, but the shots did not penetrate; the tower was intact, and it continued to revolve.”

Greene later wrote that “a look of confidence passed over the men’s faces, and we believed the Merrimack would not repeat the work it had accomplished the day before.” One gunner even thought the Confederates were firing canister at them, as the shots “rattled on our iron decks like hailstones.”

Worden recalled that “at this period I felt some anxiety about the turret machinery, it having been predicted by many persons that a heavy shot with great initial velocity striking the turret would so derange it as to stop its working; but finding that it had been twice struck and still revolved as freely as ever, I turned back with renewed confidence and hope, and continued the engagement at close quarters; every shot from our guns taking effect on the high sides of our adversary, stripping off the iron freely.” This was the ultimate test of Ericsson’s invention. Both the Monitor’s hull and turret armor were proof to the rifled shot fired by its opponent. Worden “passed slowly by it, within a few yards, delivering fire as rapidly as possible and receiving from it a rapid fire in return, both from its great guns and musketry – the latter aimed at the pilot house, hoping undoubtedly to penetrate through the lookout holes and to disable the commanding officer and the helmsman.”

Although the Virginia maintained a heavy fire, its shot seemed to be incapable of damaging the Monitor. Officers in the attendant flotilla of Confederate vessels near Sewell’s Point were heard to say “the unknown craft was a wicked thing, and that we better not get too near it.” It was becoming increasingly apparent that the Virginia had met its match.

A battle of maneuver

After two hours of dueling, both captains were beginning to realize that they had little chance of damaging their opponent through gunfire alone. While Jones had the option of trying to maneuver closer to the Minnesota to attack it, both captains could also try to ram their opponent. The duel continued, but instead of a contest between two ships steaming in circles around each other, around 11.00am Jones and Worden began to try other stratagems. Of the two ships, the Monitor was by far the more maneuverable, and Worden decided to try to ram the stern of its opponent, hoping to damage its screw (propeller) or rudder. If the Virginia could be disabled, then the Monitor could find a blind spot and pour fire into it without danger. First, Worden had to deal with a logistical problem. His guns had run out of ammunition, and in order to replenish the supplies within the turret, he had to disengage, and steam away from his opponent. Shot was brought up out of the hold, and while this was going on, Jones edged his ship closer to the Minnesota. Both he and his pilot were unsure of how deep the water was beneath their keel, and by the time they had charted a course to get as close to the wooden frigate as they could, the Monitor was steaming back into the fray. Worden made a dash for the Virginia’s stern, but missed by just two feet. Jones also decided to break the circling pattern adopted by the two ships in an attempt to attack the Minnesota. He steered northwest, forcing the Monitor to chase after him, and try to cut in between the Virginia and the stranded frigate. Just at that moment, in Lieutenant Jones’s words, “In spite of all the cares of our pilots, we ran ashore”. The surgeon, Dr. Phillips, was less reluctant to place blame: “the pilot purposely ran us aground nearly two miles off from the Minnesota, fearing that frigate’s terrible broadside.” This was a potential disaster for the Confederates, and Worden was quick to take advantage of their plight. He laid his ship alongside the Virginia so that the smaller ironclad lay beneath the muzzles of the Confederate guns. As Van Brunt described it; “the contrast was that of a pygmy to a giant.” Phillips recalled that “it directed a succession of shots at the same section of our vessel, and some of them striking close together, started the timbers and drove them perceptibly in … it began to sound every chink in our armor – every one but that which was actually vulnerable, had it known it.” He was referring to the waterline. As the Virginia burned coal, it became lighter, and consequently its protective knuckle at the bottom of the casemate rose closer to the surface. It was designed to extend almost three feet below the waterline. After two days of fighting, it was only six inches below the surface. As Ramsay reported: “Lightened as we were, these exposed portions rendered us no longer an ironclad, and the Monitor might have pierced us between wind and water had it depressed its gun.”

No comments:

Post a Comment