https://ospreypublishing.com/thisweekhistory/

Żołnierze argentyńscy lądują na Falklandach 2 kwietnia 1982 r.

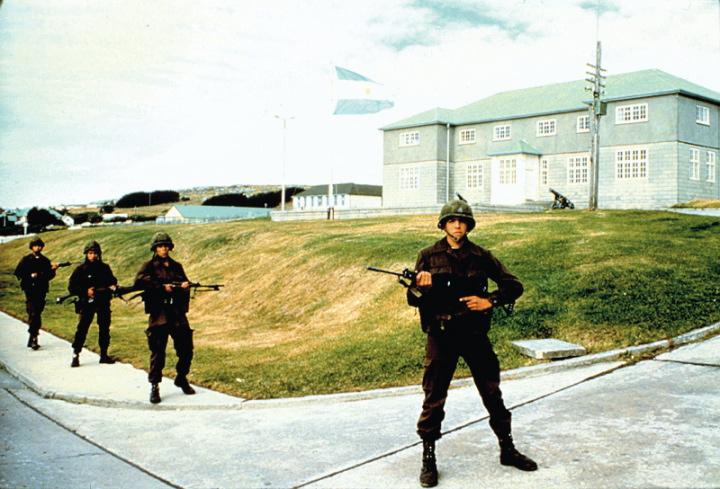

Argentyńscy żołnierze piechoty morskiej przed domem gubernatora w Port Stanley

Sea harriery w locie bojowym na Falklandach

Francuska rakieta Exocet

Śmigłowiec transportowy CH-47 Chinook dostarcza zaopatrzenie dla wojsk brytyjskich na Falklandach

Brytyjskie okręty desantowe podczas lądowania pod San Carlos

Okręty brytyjskie opuszczają port w Portsmouth

Brytyjski okręt podwodny HMS Conqueror

Argentyński krążownik „General Belgrano”

Lotniskowiec HMS „Hermes”

Żołnierze brytyjskiej piechoty morskiej lądujący na Falkandach

Start samolotu Sea Harrier z lotniskowca

Fregata HMS „Antelope” tonie pod San Carlos, 23 maja 1982 r.

Starszy sierżant argentyńskiej piechoty morskiej w hełmie amerykańskim, w ocieplanej parce, uzbrojony w belgijski karabin szturmowy FAL PARA i pistolet Browning

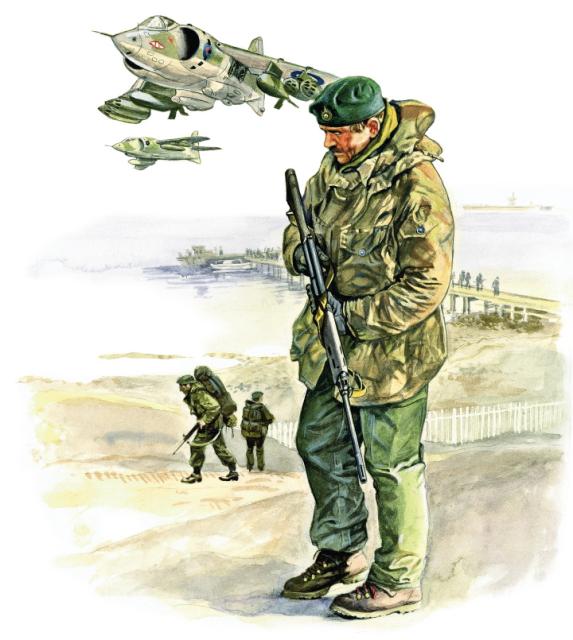

Brytyjski marine w kamuflażowej parce uzbrojony w karabin FAL L4A2. W powietrzu myśliwce Sea Harrier

Oddział brytyjskiej piechoty morskiej na pokładzie lotniskowca HMS „Hermes” przed desantem na Falklandach

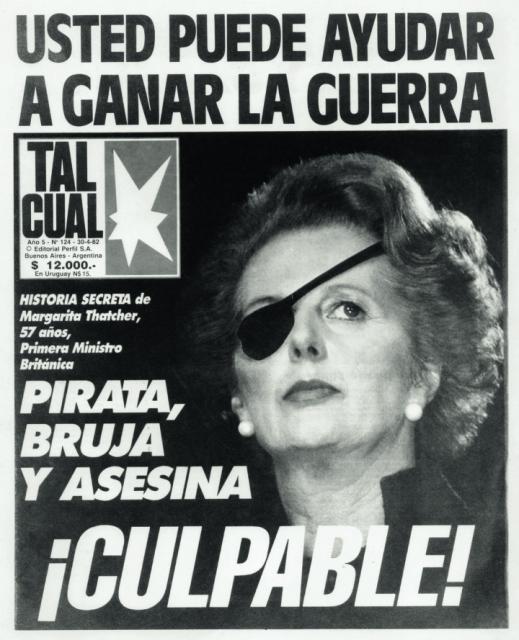

Argentyńska propaganda nie przebierała w środkach, nazywając premier Margaret Thatcher piratką, wiedźmą, i morderczynią

Leopoldo Fortunato Galtieri (1926 – 2003)

John Forster „Sandy” Woodward (1932)

Brytyjscy marines wieszają flagę przed domem gubernatora w Port Stanley 15 czerwca 1982 r.

Jeńcy argentyńscy w prowizorycznym obozie pod Port Stanley

Książę Andrew, pilot śmigłowca na HMS „Hermes”, podczas uroczystego powitania floty brytyjskiej powracającej z Falklandów

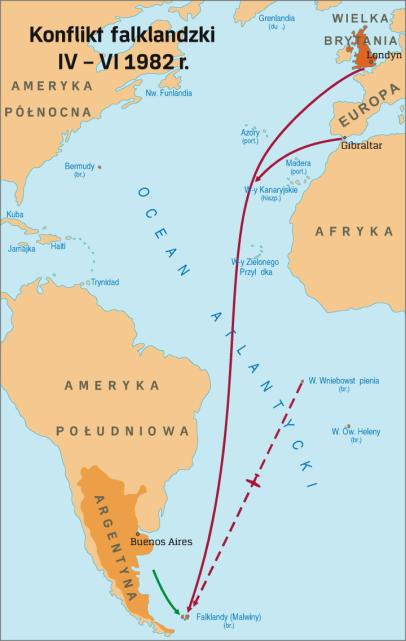

An extract from Essential Histories 15: The Falklands War 1982Race to the islands: Argentina and Britain deploy their forces

Britain’s official position in April 1982 was that she preferred to resolve the crisis through diplomatic negotiation, and would only employ the task force if peaceful means failed. In fact, it was the exigencies of military operations that set the timetable, not the requirements of the diplomats. This is not to say there were not elements within Britain who were working desperately for a peaceful outcome. The new Foreign Secretary, Francis Pym, laboured earnestly for a compromise, though it was rumoured within some sections of the Conservative Party that his real purpose was to inflict political damage on his arch rival, the Prime Minister. Al Haig, the US Secretary of State, an old friend of Pym’s, conducted a frenetic ‘shuttle diplomacy’, which attempted to address both Argentine and British requirements, and in the end satisfied neither. Mrs Thatcher was much more in tune with the mood of the British people than was Francis Pym and other Conservative grandees. She sensed that they were not much interested in a peaceful compromise and nor was she. Nothing less than an Argentine departure from the islands with British sovereignty fully restored would do, and this was a price she strongly suspected the Junta could not afford to pay.

A ghost that had haunted a generation of British Prime Ministers whenever they considered military action was that of the Suez Canal debacle of 1956. Determined not to repeat the mistakes of Anthony Eden, Mrs Thatcher consulted two previous Prime Ministers, the Earl of Stockton (Harold Macmillan) and Lord Callaghan, who told her to keep political and military activity tightly coordinated. She therefore decided to establish an inner committee to manage the crisis, which was quickly dubbed the ‘War Cabinet’. Chaired by the Prime Minister, the War Cabinet included Francis Pym, Defence Secretary John Nott, Home Secretary William Whitelaw, Chancellor of the Exchequer Geoffrey Howe and Chairman of the Conservative Party Cecil Parkinson. It had as its professional advisers a team of key civil servants and service chiefs, led by the Chief of the Defence Staff Sir Terence Lewin. The composition of the War Cabinet meant that the diplomatic and domestic political ramifications of any military action could be quickly assessed and appropriate instructions issued. Likewise, British diplomacy could be used to increase the likelihood of a peaceful solution rather than the avoidance of a military solution.

Thus the main thrust of Britain’s diplomatic effort was not to effect a compromise but to place Argentina in the wrong, to isolate her, and to keep her isolated. Argentina’s Foreign Ministry attempted to respond, but its efforts were feeble and poorly coordinated. It was a most unequal competition between a heavyweight diplomatic machine which had been playing power politics on the world stage for more than four centuries, and a foreign ministry that could just about manage relations with a few of its Latin American neighbours. While Mrs Thatcher was bearing the wrath of the House of Commons on 3 April, Britain’s ambassador to the United Nations, Sir Anthony Parsons, engineered the passage of Resolution 502 through the Security Council, which stressed the illegitimacy of the use of force and called for an immediate withdrawal of Argentine forces. On the same day the Foreign Office secured France’s agreement to halt the export to Argentina of Exocet missiles, Super Etendard Aircraft and engines for Pucara aircraft, all of which would seriously compromise Argentina’s military capability. The impact of this ban was extended on 9 April, when Britain managed to secure an EEC trade embargo on Argentina for one month, with an option to extend the embargo further.

The great diplomatic prize was winning the support of the United States. Argentina had placed her hopes in the close personal relationship that had developed between Galtieri and some of the American military, which included Al Haig, and in the support of Jeane Kirkpatrick, the US ambassador to the United Nations, and a friend of Argentine Foreign Minister Costa Mendez. In fact, there was not the slightest prospect of the United States supporting Argentina against Great Britain. It was not merely that America and Britain shared a history and a culture and subscribed to identical values. With the Cold War entering what proved to be its final and most dangerous phase, a major ally such as Britain would inevitably be regarded as more important than a relatively remote country in the southern hemisphere. US Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger let it be known that he wanted the military to ‘give the Brits every possible assistance, but not, under any circumstances, to be caught doing so’. Weinberger’s decision was of the utmost importance. Without American logistic support, most of which was channelled through Ascension Island, the operation would have taken much longer, and would undoubtedly have been compromised by the onset of the southern winter.

With this intense diplomatic activity going on in the background, the first elements of the task force, the carriers Hermes and Invincible, sailed from Portsmouth on 5 April. Over the next few weeks British ports saw many departures, most spectacularly that of Canberra carrying 40 and 45 Commando of the Royal Marines and 3rd Battalion of the Parachute Regiment, all of which attracted immense media interest. The emphasis was on speed, because these highly publicised sailings were designed to send a strong message to Buenos Aires and as a result the loading had often been chaotic. The actual assembly of the task force took place in mid-April, as ships rendezvoused in the Georgetown Roads off Ascension Island, a 3,000-foot volcanic cone almost exactly halfway between the British Isles and the Falklands. In 1943 American engineers had constructed Wideawake airfield on a steep lava flow at the foot of the volcano, and this had since been developed into a major base. British servicemen who flew in recalled that Ascension, its barren volcanic crags festooned with aerials and satellite dishes, reminded them of Tracey Island, the secret base of Thunderbirds, a children’s television programme popular in the 1960s.

The stop at Ascension was essential, for it enabled the British to organise not just the shipping but also a command chain. As this was an ‘out of area’ operation dependent on the Royal Navy the Commander-in-Chief Fleet, Admiral Sir John Fieldhouse, based at Northwood, was designated Task Force Commander, reporting directly to Admiral Lewin, the CDS. The commander of the Royal Marines, Major General Jeremy Moore, was appointed Fieldhouse’s land forces deputy. Under Fieldhouse were the operational commanders: Rear Admiral John ‘Sandy’ Woodward, appointed to command the carriers and surface warships, Commodore Michael Clapp, given command of the amphibious ships, including Fearless and Intrepid, and Brigadier Julian Thompson, commanding the Landing Task Group. A major problem with this arrangement was the absence of an on-the-spot theatre commander to co-ordinate the activities of the three operational commanders with Northwood, but this was not apparent at the time. Another difficulty was caused by Fieldhouse’s insistence that the submarines take orders from Northwood, rather than from Woodward.

The first problem the commanders had to face was planning the logistics, for they all knew that the key to Operation Corporate was the ability of the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force to construct and maintain an 8,000-mile supply line that would be capable of sustaining military forces in the South Atlantic. An air bridge from Britain to Wideawake would have been impossible if the US Air Force had not handed over 12.5 million gallons of highly refined aviation fuel. With this, the 54 Hercules C-130s of 24, 30, 47 and 70 squadrons and the 13 VC 10s of 10 squadron, supplemented by three Belfast strategic freighters and a number of Boeing 707s, managed 2,500 flights between the beginning of April and the middle of June, which delivered some 30,000 tons of freight and several thousand personnel. Equally important was the work of the helicopters, which allowed chaotically stowed supplies to be sorted out, cross-decked, and combat loaded. All this involved 10,600 helicopter movements. The busiest day was 16 April, when 300 fixed wing and helicopter flights were recorded, making Wideawake the world’s busiest airport.

The most important shipping movements in the early part of the campaign were not the highly publicised departures of the aircraft carriers and the Canberra, but the sailing of nine Royal Fleet Auxiliary oil tankers, soon supplemented by another 14 tankers taken up from trade, for without these ships the task force would be unable to proceed. Beginning on 2 April the Defence Operations Movement Staff (DOMS) in the Ministry of Defence contracted and requisitioned 68 ships from 33 different companies, which ranged from the luxury liners like Canberra and the QE2 to North Sea tug boats. In addition, the Royal Fleet Auxiliary provided 16 cargo transports, bringing the total number of ships sustaining the task force to 84, about the size of a large Second World War convoy.

All these transports were required to keep the warships of the task force, two aircraft carriers, five destroyers, 11 frigates and three nuclear submarines, operating in the South Atlantic for just six weeks. The submarines, Conqueror, Spartan and Splendid, capable of 25 knots submerged, raced ahead to blockade the Falklands, and to seek out and destroy Argentine submarines. When they arrived some days later the carriers would employ their 20 Sea Harrier aircraft to attack Port Stanley airfield and other Argentine bases. Although the Fleet Air Arm pilots were supremely confident of their ability to engage in successful air combat with Argentine Mirage IIICs, trial combats then being conducted between RAF Harriers and French Mirages suggested that the Mirage was the superior aircraft. This disparity was no longer a cause for concern. Ever since the Israeli Air Force had been shot out of the sky by Egyptian and Syrian anti-aircraft missile systems at the beginning of the Yom Kippur War in October 1973, it had been an article of faith that air superiority could be attained by ground- or sea-based missiles. Nowhere was this belief stronger than in the Royal Navy, whose destroyers and frigates bristled with Sea Cats, Sea Wolfs and Sea Darts. Royal Navy ships were also equipped with ship-to-ship Exocet missiles, which would be more than adequate to deal with a threat from any Argentine warships. It was known that the Argentines were also acquiring Exocets, but it was believed that none were in operation before France withdrew technical support. British warships also had guns, and these would be used to bombard Argentine positions prior to a landing.

The object of all this air and sea activity was to put a landing force ashore in the Falklands. As this was an amphibious operation it was axiomatic that the three Commandos (40, 42 and 45, each of 500 men) of 3 Commando Brigade, Royal Marines, would spearhead the assault. The 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the Parachute Regiment, possibly the only troops of the army at that time whose general standard of training and fitness was equal to that of the Marines, were attached to 3 Brigade, along with two troops of light tanks from the Blues and Royals, and Air Defence Regiments from the Royal Artillery. Squadrons of 22 Special Air Service, who would conduct reconnaissance missions and carry out raids, were also aboard the transports. All told, the assault force numbered just 7,000 men, who were amongst the fittest, the best trained and the most highly motivated of any soldiers in the world.

In Argentina the euphoria that had greeted the ‘liberation’ of the Malvinas, steadily gave way to disbelief and alarm, as the magnitude of British preparations for war became ever more apparent. Brigadier General Mario Menendez had arrived in Stanley on 7 April to assume the role of governor, not of garrison commander, but he soon found himself overseeing a desperate build-up of men and materiel. The navy devoted all five of its transports, and also chartered ships from Argentina’s national shipping line. In all nine ships displacing a total of 80,000 tons were loaded, of which eight successfully completed the voyage before British submarines reached the area. Argentina supplemented shipping with an airbridge. Between 2 and 29 April the air force’s nine Hercules C-130 transports assisted by a small number of Fokker F28s, Navy Lockheed Electras and Argentine National Airlines Boeing 737s and BAC 111s flew around the clock. A total of 500 landings were made at Stanley airfield, bringing 10,700 men and 5,500 tons of supplies, mainly weapons and ammunition. Movement by air meant that heavy equipment or equipment deemed non-essential such as tents, cooking utensils and entrenching tools were removed from units and sent by the few merchant ships that dared the exclusion zone. On average, three weeks were to elapse before units were married up with their equipment but in many cases equipment did not reach the islands at all.

The first reinforcements to arrive came from the 10 Infantry Brigade under Brigadier General Oscar Joffre, reinforced by 3 Infantry Brigade under Brigadier General Omar Parada on 24 April. Unlike the all-volunteer British army, the Argentine army was composed of conscripts. An early problem was the need to replace the January 1982 intake of 19-year-old conscripts (the class of 1963) who filled Parada’s and Joffre’s brigades with the recently discharged 20-year-old ‘veterans’ of the class of 1962. This process resulted in some disorganisation. The only units that escaped this were Argentina’s Marine regiments, which, unlike the army, inducted one-sixth of the conscripts they required every two months. Thus at any one time the great majority of a Marine regiment had completed at least its basic training. About a month after the landing Argentina had deployed some 13,000 men to the islands, which comprised eight infantry and two Marine regiments, an Argentine regiment being equivalent to a British battalion. The army had also sent a number of artillery units, which could field 42 105mm and four 155mm guns and 23 quick-firing anti-aircraft guns.These were supplemented by a number of Roland and Tiger Cat surface-to-air missile launchers and heavy machine gun units, which boasted about 40 12.7mm guns. Argentina decided against deploying heavy armour, but did send a light reconnaissance squadron with 27 armoured cars.

It was easy enough to pour troops and equipment into the islands, but less easy to arrive at a coherent scheme of defence that made best use of Argentina’s air and naval forces, as well as her land forces. On 7 April Argentina attempted to create a degree of inter-service co-operation by establishing the South Atlantic Operational Theatre under Vice Admiral Lombardo. On the islands there was an unseemly squabble for dominance between Menendez and the senior representatives of the navy and the air force, Rear-Admiral Edgardo Otero and Brigadier General Luis Castellano. The manoeuvring came to a formal conclusion on 26 April when Menendez appointed himself as head of the Malvinas Joint Command, a usurpation which won the approval of the Junta. The conflict now became internecine, and was complicated by the fact that Menendez was junior to his two army brigadier generals, Joffre and Parada, both of whom tended to treat his orders as suggestions. By the end of April five brigadier generals and a rear-admiral had set up their headquarters in Stanley, each with their own not inconsiderable staff, comprising, by one calculation, about 3,000 of the 13,000 men Argentina had sent to the Falklands. To make matters worse, any hope of developing a coherent defence plan collapsed after 19 April when individual members of the Junta dealt with Menendez directly, each representing their own service rather than the armed forces as a whole. Admiral Anaya visited Menendez on 19, Lami Dozo on 20 April, the Chief of Staff General Cristino Nicholaides on 21 April, and Galtieri on 22 April.

When the shooting started Argentina’s first line of defence would be the Fuerza Aerea Argentina (FAA) (air force), with some 120 high-performance combat jet aircraft, more than enough to overwhelm the Royal Navy’s defensive systems. The British feared that the FAA would extend Stanley’s 4,700-foot airfield with steel matting so that it would be long enough to allow Mirages, Daggers and Skyhawks to operate from it. Argentina had ample supplies of steel matting and enough time to ship it to Stanley, but when air force engineers studied the practicalities they decided it would be too difficult to sustain high-performance jet aircraft from such a primitive field. Super-Etendards and Daggers required specialised fuel storage facilities, workshops capable of maintaining and repairing sophisticated avionics and weapons systems, and hardened bunkers to protect the aircraft from British attack. High performance aircraft based at Stanley without these facilities would be essentially single-shot weapons. If they did not destroy the British in their first operation the British would almost certainly destroy them.

This decision meant that the FAA’s first line combat aircraft would be forced to operate from bases in Argentina. Skyhawk A-4Bs and Mirage III Es were deployed to Rio Gallegos in the south-east of Patagonia; Skyhawk A-4Cs and Daggers were based at San Julian, 180 miles to the north; long-range Canberra bombers would fly from Trelew another 450 miles further north, while Daggers were sent to Rio Grande on the north-east coast of Tierra del Fuego, along with the navy’s Skyhawk A-4Qs and Super Etendards. By the end of April about 80 machines were in the southern bases, approximately two-thirds of Argentina’s first line air strength. Air operations were to be controlled from a command set up at Comodoro Rivadavia air base on the coast of central Patagonia, which would rely on information supplied by a long-range Westinghouse AN/TPS-43 F radar set up in Port Stanley. Most of the bases were more than 400 miles from the islands, which severely limited the time aircraft could spend in the area. In- flight refuelling could extend the range, but the FAA had only three tanker aircraft, and only the 60 Skyhawks and the five Super Etendards had an in-flight refuelling capability.

Thanks to Argentina’s counter-insurgency operations, the FAA was lavishly equipped with Pucara IA-58 ground attack aircraft, about 30 of which were flown to Stanley and to the airfield at the Falkland’s second settlement, Darwin–Goose Green. The navy reinforced the AAF, sending six Aermacchi MB.339A advanced jet trainers converted to a ground attack role to Stanley and six Beechcraft T-34 C-1 Turbo Mentor trainers, equipped with a variety of weapons pods, to operate from a grass runway on Pebble Island, which the Argentines christened Calderon Naval Air Station. The aircraft based in the Falklands, while lacking the capacity to attack the task force directly, could supplement the attacks of mainland-based jets. In addition, the Argentine army deployed a number of light transport aircraft to the islands, and 27 helicopters, including three heavy-lift Chinooks.

The Argentine navy, with four submarines an aircraft carrier, and a number of Exocet-equipped warships, also had the capability to attack the task force while it was well to the north of the islands. But like the FAA, the naval high command decided that a deployment too far forward risked playing to British strengths. The Royal Navy, for example, was the world leader in anti-submarine warfare, and any attempt by Argentina’s four boats to attack the Task Force as it sailed south of Ascension was likely to end in their loss. It was felt the same fate would befall any Argentine surface units, particularly old ships like the aircraft carrier and the cruiser Belgrano, which ventured in range of the Task Force without the benefit of land-based air support. The navy decided to wait until the British were heavily involved in an air–sea engagement to hit them with simultaneous surface and submarine attacks.

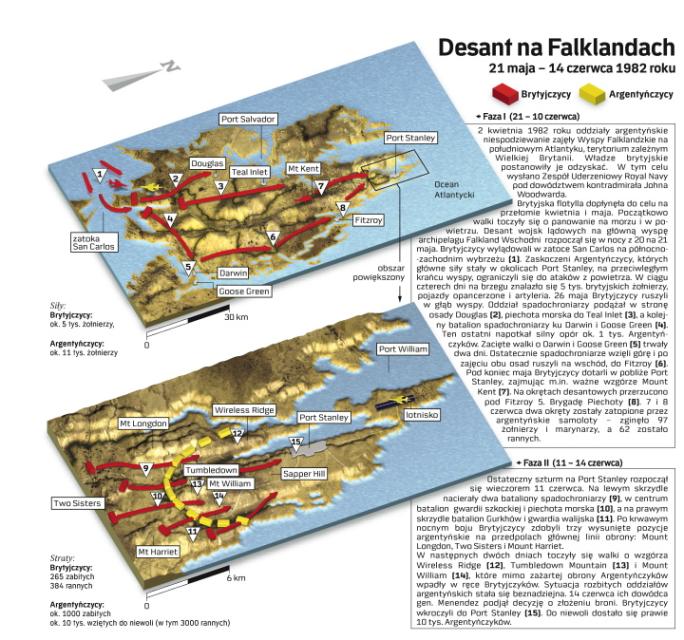

If the FAA and the navy failed to prevent a British landing, it would be up to Menendez’s young conscripts to defeat them in a land battle. Menendez had too few troops to prevent a landing at some point on the heavily indented coastline of the islands which were about 4,000 square miles in area, about half the size of Wales. He sent 800 men to Port Howard and another 900 to Fox Bay to establish a presence on West Falkland Island, with a detachment of 120 to Pebble Island, and about 1,200 to Darwin–Goose Green. Menendez knew that the vital ground was Port Stanley with its airfield and harbour. If he could hold this area long enough the British logistic system would inevitably break down, and they would be forced to withdraw from the South Atlantic. He therefore concentrated the bulk of his forces in an all round defence, with the 25th, 6th and 3rd regiments dug in to cover the beaches from the airfield to Mullett Creek, while the 5th Marines and the 4th and 7th regiments were dug into the hills and mountains to the west of Stanley, Mt Harriet, Two Sisters, Tumbledown, Mt Longdon and Wireless Ridge. Menendez placed most of his artillery in and around Stanley, from where it could support the forces on the beaches or in the mountains, and where it would be protected from British attack by the proximity of the civilian population. His plan was to fight an attritional battle from fixed defences, which was subsequently much criticised, but which suited admirably the capabilities of the soldiers he had at his disposal.

Further Reading:Essential Histories 15: The Falklands War 1982 explores both the military and political dimensions of this important conflict, including detailed accounts of the air / sea battle, the Battle for San Carlos Water, Goose Green, Mt Harriet, Tumbledown and many others.

Men-at-Arms 133: Battle for the Falklands (1) Land Forces details the history, uniforms and equipment of the land forces that contested the Falklands War.

Men-at-Arms 134: Battle for the Falklands (2) Naval Forces examines the Argentine Marines and Royal Marines who fought in the battle for the Falklands.

Men-at-Arms 250: Argentine Forces in the Falklands examines the history, organization and equipment of the Argentine forces that battled for control of this remote British outpost.

Combat Aircraft 28: Air War in the Falklands 1982 shows how the key to British success was the speed with which the British gained and then maintained air superiority over the islands and the waters around them with their small force of Sea Harrier STOVL warplanes, which operated from two aircraft carriers.

Żołnierze argentyńscy lądują na Falklandach 2 kwietnia 1982 r.

Argentyńscy żołnierze piechoty morskiej przed domem gubernatora w Port Stanley

Sea harriery w locie bojowym na Falklandach

Francuska rakieta Exocet

Śmigłowiec transportowy CH-47 Chinook dostarcza zaopatrzenie dla wojsk brytyjskich na Falklandach

Brytyjskie okręty desantowe podczas lądowania pod San Carlos

Okręty brytyjskie opuszczają port w Portsmouth

Brytyjski okręt podwodny HMS Conqueror

Argentyński krążownik „General Belgrano”

Lotniskowiec HMS „Hermes”

Żołnierze brytyjskiej piechoty morskiej lądujący na Falkandach

Fregata HMS „Antelope” tonie pod San Carlos, 23 maja 1982 r.

Starszy sierżant argentyńskiej piechoty morskiej w hełmie amerykańskim, w ocieplanej parce, uzbrojony w belgijski karabin szturmowy FAL PARA i pistolet Browning

Brytyjski marine w kamuflażowej parce uzbrojony w karabin FAL L4A2. W powietrzu myśliwce Sea Harrier

Oddział brytyjskiej piechoty morskiej na pokładzie lotniskowca HMS „Hermes” przed desantem na Falklandach

Argentyńska propaganda nie przebierała w środkach, nazywając premier Margaret Thatcher piratką, wiedźmą, i morderczynią

Leopoldo Fortunato Galtieri (1926 – 2003)

John Forster „Sandy” Woodward (1932)

Brytyjscy marines wieszają flagę przed domem gubernatora w Port Stanley 15 czerwca 1982 r.

Jeńcy argentyńscy w prowizorycznym obozie pod Port Stanley

Książę Andrew, pilot śmigłowca na HMS „Hermes”, podczas uroczystego powitania floty brytyjskiej powracającej z Falklandów

An extract from Essential Histories 15: The Falklands War 1982Race to the islands: Argentina and Britain deploy their forces

Britain’s official position in April 1982 was that she preferred to resolve the crisis through diplomatic negotiation, and would only employ the task force if peaceful means failed. In fact, it was the exigencies of military operations that set the timetable, not the requirements of the diplomats. This is not to say there were not elements within Britain who were working desperately for a peaceful outcome. The new Foreign Secretary, Francis Pym, laboured earnestly for a compromise, though it was rumoured within some sections of the Conservative Party that his real purpose was to inflict political damage on his arch rival, the Prime Minister. Al Haig, the US Secretary of State, an old friend of Pym’s, conducted a frenetic ‘shuttle diplomacy’, which attempted to address both Argentine and British requirements, and in the end satisfied neither. Mrs Thatcher was much more in tune with the mood of the British people than was Francis Pym and other Conservative grandees. She sensed that they were not much interested in a peaceful compromise and nor was she. Nothing less than an Argentine departure from the islands with British sovereignty fully restored would do, and this was a price she strongly suspected the Junta could not afford to pay.

A ghost that had haunted a generation of British Prime Ministers whenever they considered military action was that of the Suez Canal debacle of 1956. Determined not to repeat the mistakes of Anthony Eden, Mrs Thatcher consulted two previous Prime Ministers, the Earl of Stockton (Harold Macmillan) and Lord Callaghan, who told her to keep political and military activity tightly coordinated. She therefore decided to establish an inner committee to manage the crisis, which was quickly dubbed the ‘War Cabinet’. Chaired by the Prime Minister, the War Cabinet included Francis Pym, Defence Secretary John Nott, Home Secretary William Whitelaw, Chancellor of the Exchequer Geoffrey Howe and Chairman of the Conservative Party Cecil Parkinson. It had as its professional advisers a team of key civil servants and service chiefs, led by the Chief of the Defence Staff Sir Terence Lewin. The composition of the War Cabinet meant that the diplomatic and domestic political ramifications of any military action could be quickly assessed and appropriate instructions issued. Likewise, British diplomacy could be used to increase the likelihood of a peaceful solution rather than the avoidance of a military solution.

Thus the main thrust of Britain’s diplomatic effort was not to effect a compromise but to place Argentina in the wrong, to isolate her, and to keep her isolated. Argentina’s Foreign Ministry attempted to respond, but its efforts were feeble and poorly coordinated. It was a most unequal competition between a heavyweight diplomatic machine which had been playing power politics on the world stage for more than four centuries, and a foreign ministry that could just about manage relations with a few of its Latin American neighbours. While Mrs Thatcher was bearing the wrath of the House of Commons on 3 April, Britain’s ambassador to the United Nations, Sir Anthony Parsons, engineered the passage of Resolution 502 through the Security Council, which stressed the illegitimacy of the use of force and called for an immediate withdrawal of Argentine forces. On the same day the Foreign Office secured France’s agreement to halt the export to Argentina of Exocet missiles, Super Etendard Aircraft and engines for Pucara aircraft, all of which would seriously compromise Argentina’s military capability. The impact of this ban was extended on 9 April, when Britain managed to secure an EEC trade embargo on Argentina for one month, with an option to extend the embargo further.

The great diplomatic prize was winning the support of the United States. Argentina had placed her hopes in the close personal relationship that had developed between Galtieri and some of the American military, which included Al Haig, and in the support of Jeane Kirkpatrick, the US ambassador to the United Nations, and a friend of Argentine Foreign Minister Costa Mendez. In fact, there was not the slightest prospect of the United States supporting Argentina against Great Britain. It was not merely that America and Britain shared a history and a culture and subscribed to identical values. With the Cold War entering what proved to be its final and most dangerous phase, a major ally such as Britain would inevitably be regarded as more important than a relatively remote country in the southern hemisphere. US Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger let it be known that he wanted the military to ‘give the Brits every possible assistance, but not, under any circumstances, to be caught doing so’. Weinberger’s decision was of the utmost importance. Without American logistic support, most of which was channelled through Ascension Island, the operation would have taken much longer, and would undoubtedly have been compromised by the onset of the southern winter.

With this intense diplomatic activity going on in the background, the first elements of the task force, the carriers Hermes and Invincible, sailed from Portsmouth on 5 April. Over the next few weeks British ports saw many departures, most spectacularly that of Canberra carrying 40 and 45 Commando of the Royal Marines and 3rd Battalion of the Parachute Regiment, all of which attracted immense media interest. The emphasis was on speed, because these highly publicised sailings were designed to send a strong message to Buenos Aires and as a result the loading had often been chaotic. The actual assembly of the task force took place in mid-April, as ships rendezvoused in the Georgetown Roads off Ascension Island, a 3,000-foot volcanic cone almost exactly halfway between the British Isles and the Falklands. In 1943 American engineers had constructed Wideawake airfield on a steep lava flow at the foot of the volcano, and this had since been developed into a major base. British servicemen who flew in recalled that Ascension, its barren volcanic crags festooned with aerials and satellite dishes, reminded them of Tracey Island, the secret base of Thunderbirds, a children’s television programme popular in the 1960s.

The stop at Ascension was essential, for it enabled the British to organise not just the shipping but also a command chain. As this was an ‘out of area’ operation dependent on the Royal Navy the Commander-in-Chief Fleet, Admiral Sir John Fieldhouse, based at Northwood, was designated Task Force Commander, reporting directly to Admiral Lewin, the CDS. The commander of the Royal Marines, Major General Jeremy Moore, was appointed Fieldhouse’s land forces deputy. Under Fieldhouse were the operational commanders: Rear Admiral John ‘Sandy’ Woodward, appointed to command the carriers and surface warships, Commodore Michael Clapp, given command of the amphibious ships, including Fearless and Intrepid, and Brigadier Julian Thompson, commanding the Landing Task Group. A major problem with this arrangement was the absence of an on-the-spot theatre commander to co-ordinate the activities of the three operational commanders with Northwood, but this was not apparent at the time. Another difficulty was caused by Fieldhouse’s insistence that the submarines take orders from Northwood, rather than from Woodward.

The first problem the commanders had to face was planning the logistics, for they all knew that the key to Operation Corporate was the ability of the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force to construct and maintain an 8,000-mile supply line that would be capable of sustaining military forces in the South Atlantic. An air bridge from Britain to Wideawake would have been impossible if the US Air Force had not handed over 12.5 million gallons of highly refined aviation fuel. With this, the 54 Hercules C-130s of 24, 30, 47 and 70 squadrons and the 13 VC 10s of 10 squadron, supplemented by three Belfast strategic freighters and a number of Boeing 707s, managed 2,500 flights between the beginning of April and the middle of June, which delivered some 30,000 tons of freight and several thousand personnel. Equally important was the work of the helicopters, which allowed chaotically stowed supplies to be sorted out, cross-decked, and combat loaded. All this involved 10,600 helicopter movements. The busiest day was 16 April, when 300 fixed wing and helicopter flights were recorded, making Wideawake the world’s busiest airport.

The most important shipping movements in the early part of the campaign were not the highly publicised departures of the aircraft carriers and the Canberra, but the sailing of nine Royal Fleet Auxiliary oil tankers, soon supplemented by another 14 tankers taken up from trade, for without these ships the task force would be unable to proceed. Beginning on 2 April the Defence Operations Movement Staff (DOMS) in the Ministry of Defence contracted and requisitioned 68 ships from 33 different companies, which ranged from the luxury liners like Canberra and the QE2 to North Sea tug boats. In addition, the Royal Fleet Auxiliary provided 16 cargo transports, bringing the total number of ships sustaining the task force to 84, about the size of a large Second World War convoy.

All these transports were required to keep the warships of the task force, two aircraft carriers, five destroyers, 11 frigates and three nuclear submarines, operating in the South Atlantic for just six weeks. The submarines, Conqueror, Spartan and Splendid, capable of 25 knots submerged, raced ahead to blockade the Falklands, and to seek out and destroy Argentine submarines. When they arrived some days later the carriers would employ their 20 Sea Harrier aircraft to attack Port Stanley airfield and other Argentine bases. Although the Fleet Air Arm pilots were supremely confident of their ability to engage in successful air combat with Argentine Mirage IIICs, trial combats then being conducted between RAF Harriers and French Mirages suggested that the Mirage was the superior aircraft. This disparity was no longer a cause for concern. Ever since the Israeli Air Force had been shot out of the sky by Egyptian and Syrian anti-aircraft missile systems at the beginning of the Yom Kippur War in October 1973, it had been an article of faith that air superiority could be attained by ground- or sea-based missiles. Nowhere was this belief stronger than in the Royal Navy, whose destroyers and frigates bristled with Sea Cats, Sea Wolfs and Sea Darts. Royal Navy ships were also equipped with ship-to-ship Exocet missiles, which would be more than adequate to deal with a threat from any Argentine warships. It was known that the Argentines were also acquiring Exocets, but it was believed that none were in operation before France withdrew technical support. British warships also had guns, and these would be used to bombard Argentine positions prior to a landing.

The object of all this air and sea activity was to put a landing force ashore in the Falklands. As this was an amphibious operation it was axiomatic that the three Commandos (40, 42 and 45, each of 500 men) of 3 Commando Brigade, Royal Marines, would spearhead the assault. The 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the Parachute Regiment, possibly the only troops of the army at that time whose general standard of training and fitness was equal to that of the Marines, were attached to 3 Brigade, along with two troops of light tanks from the Blues and Royals, and Air Defence Regiments from the Royal Artillery. Squadrons of 22 Special Air Service, who would conduct reconnaissance missions and carry out raids, were also aboard the transports. All told, the assault force numbered just 7,000 men, who were amongst the fittest, the best trained and the most highly motivated of any soldiers in the world.

In Argentina the euphoria that had greeted the ‘liberation’ of the Malvinas, steadily gave way to disbelief and alarm, as the magnitude of British preparations for war became ever more apparent. Brigadier General Mario Menendez had arrived in Stanley on 7 April to assume the role of governor, not of garrison commander, but he soon found himself overseeing a desperate build-up of men and materiel. The navy devoted all five of its transports, and also chartered ships from Argentina’s national shipping line. In all nine ships displacing a total of 80,000 tons were loaded, of which eight successfully completed the voyage before British submarines reached the area. Argentina supplemented shipping with an airbridge. Between 2 and 29 April the air force’s nine Hercules C-130 transports assisted by a small number of Fokker F28s, Navy Lockheed Electras and Argentine National Airlines Boeing 737s and BAC 111s flew around the clock. A total of 500 landings were made at Stanley airfield, bringing 10,700 men and 5,500 tons of supplies, mainly weapons and ammunition. Movement by air meant that heavy equipment or equipment deemed non-essential such as tents, cooking utensils and entrenching tools were removed from units and sent by the few merchant ships that dared the exclusion zone. On average, three weeks were to elapse before units were married up with their equipment but in many cases equipment did not reach the islands at all.

The first reinforcements to arrive came from the 10 Infantry Brigade under Brigadier General Oscar Joffre, reinforced by 3 Infantry Brigade under Brigadier General Omar Parada on 24 April. Unlike the all-volunteer British army, the Argentine army was composed of conscripts. An early problem was the need to replace the January 1982 intake of 19-year-old conscripts (the class of 1963) who filled Parada’s and Joffre’s brigades with the recently discharged 20-year-old ‘veterans’ of the class of 1962. This process resulted in some disorganisation. The only units that escaped this were Argentina’s Marine regiments, which, unlike the army, inducted one-sixth of the conscripts they required every two months. Thus at any one time the great majority of a Marine regiment had completed at least its basic training. About a month after the landing Argentina had deployed some 13,000 men to the islands, which comprised eight infantry and two Marine regiments, an Argentine regiment being equivalent to a British battalion. The army had also sent a number of artillery units, which could field 42 105mm and four 155mm guns and 23 quick-firing anti-aircraft guns.These were supplemented by a number of Roland and Tiger Cat surface-to-air missile launchers and heavy machine gun units, which boasted about 40 12.7mm guns. Argentina decided against deploying heavy armour, but did send a light reconnaissance squadron with 27 armoured cars.

It was easy enough to pour troops and equipment into the islands, but less easy to arrive at a coherent scheme of defence that made best use of Argentina’s air and naval forces, as well as her land forces. On 7 April Argentina attempted to create a degree of inter-service co-operation by establishing the South Atlantic Operational Theatre under Vice Admiral Lombardo. On the islands there was an unseemly squabble for dominance between Menendez and the senior representatives of the navy and the air force, Rear-Admiral Edgardo Otero and Brigadier General Luis Castellano. The manoeuvring came to a formal conclusion on 26 April when Menendez appointed himself as head of the Malvinas Joint Command, a usurpation which won the approval of the Junta. The conflict now became internecine, and was complicated by the fact that Menendez was junior to his two army brigadier generals, Joffre and Parada, both of whom tended to treat his orders as suggestions. By the end of April five brigadier generals and a rear-admiral had set up their headquarters in Stanley, each with their own not inconsiderable staff, comprising, by one calculation, about 3,000 of the 13,000 men Argentina had sent to the Falklands. To make matters worse, any hope of developing a coherent defence plan collapsed after 19 April when individual members of the Junta dealt with Menendez directly, each representing their own service rather than the armed forces as a whole. Admiral Anaya visited Menendez on 19, Lami Dozo on 20 April, the Chief of Staff General Cristino Nicholaides on 21 April, and Galtieri on 22 April.

When the shooting started Argentina’s first line of defence would be the Fuerza Aerea Argentina (FAA) (air force), with some 120 high-performance combat jet aircraft, more than enough to overwhelm the Royal Navy’s defensive systems. The British feared that the FAA would extend Stanley’s 4,700-foot airfield with steel matting so that it would be long enough to allow Mirages, Daggers and Skyhawks to operate from it. Argentina had ample supplies of steel matting and enough time to ship it to Stanley, but when air force engineers studied the practicalities they decided it would be too difficult to sustain high-performance jet aircraft from such a primitive field. Super-Etendards and Daggers required specialised fuel storage facilities, workshops capable of maintaining and repairing sophisticated avionics and weapons systems, and hardened bunkers to protect the aircraft from British attack. High performance aircraft based at Stanley without these facilities would be essentially single-shot weapons. If they did not destroy the British in their first operation the British would almost certainly destroy them.

This decision meant that the FAA’s first line combat aircraft would be forced to operate from bases in Argentina. Skyhawk A-4Bs and Mirage III Es were deployed to Rio Gallegos in the south-east of Patagonia; Skyhawk A-4Cs and Daggers were based at San Julian, 180 miles to the north; long-range Canberra bombers would fly from Trelew another 450 miles further north, while Daggers were sent to Rio Grande on the north-east coast of Tierra del Fuego, along with the navy’s Skyhawk A-4Qs and Super Etendards. By the end of April about 80 machines were in the southern bases, approximately two-thirds of Argentina’s first line air strength. Air operations were to be controlled from a command set up at Comodoro Rivadavia air base on the coast of central Patagonia, which would rely on information supplied by a long-range Westinghouse AN/TPS-43 F radar set up in Port Stanley. Most of the bases were more than 400 miles from the islands, which severely limited the time aircraft could spend in the area. In- flight refuelling could extend the range, but the FAA had only three tanker aircraft, and only the 60 Skyhawks and the five Super Etendards had an in-flight refuelling capability.

Thanks to Argentina’s counter-insurgency operations, the FAA was lavishly equipped with Pucara IA-58 ground attack aircraft, about 30 of which were flown to Stanley and to the airfield at the Falkland’s second settlement, Darwin–Goose Green. The navy reinforced the AAF, sending six Aermacchi MB.339A advanced jet trainers converted to a ground attack role to Stanley and six Beechcraft T-34 C-1 Turbo Mentor trainers, equipped with a variety of weapons pods, to operate from a grass runway on Pebble Island, which the Argentines christened Calderon Naval Air Station. The aircraft based in the Falklands, while lacking the capacity to attack the task force directly, could supplement the attacks of mainland-based jets. In addition, the Argentine army deployed a number of light transport aircraft to the islands, and 27 helicopters, including three heavy-lift Chinooks.

The Argentine navy, with four submarines an aircraft carrier, and a number of Exocet-equipped warships, also had the capability to attack the task force while it was well to the north of the islands. But like the FAA, the naval high command decided that a deployment too far forward risked playing to British strengths. The Royal Navy, for example, was the world leader in anti-submarine warfare, and any attempt by Argentina’s four boats to attack the Task Force as it sailed south of Ascension was likely to end in their loss. It was felt the same fate would befall any Argentine surface units, particularly old ships like the aircraft carrier and the cruiser Belgrano, which ventured in range of the Task Force without the benefit of land-based air support. The navy decided to wait until the British were heavily involved in an air–sea engagement to hit them with simultaneous surface and submarine attacks.

If the FAA and the navy failed to prevent a British landing, it would be up to Menendez’s young conscripts to defeat them in a land battle. Menendez had too few troops to prevent a landing at some point on the heavily indented coastline of the islands which were about 4,000 square miles in area, about half the size of Wales. He sent 800 men to Port Howard and another 900 to Fox Bay to establish a presence on West Falkland Island, with a detachment of 120 to Pebble Island, and about 1,200 to Darwin–Goose Green. Menendez knew that the vital ground was Port Stanley with its airfield and harbour. If he could hold this area long enough the British logistic system would inevitably break down, and they would be forced to withdraw from the South Atlantic. He therefore concentrated the bulk of his forces in an all round defence, with the 25th, 6th and 3rd regiments dug in to cover the beaches from the airfield to Mullett Creek, while the 5th Marines and the 4th and 7th regiments were dug into the hills and mountains to the west of Stanley, Mt Harriet, Two Sisters, Tumbledown, Mt Longdon and Wireless Ridge. Menendez placed most of his artillery in and around Stanley, from where it could support the forces on the beaches or in the mountains, and where it would be protected from British attack by the proximity of the civilian population. His plan was to fight an attritional battle from fixed defences, which was subsequently much criticised, but which suited admirably the capabilities of the soldiers he had at his disposal.

Further Reading:Essential Histories 15: The Falklands War 1982 explores both the military and political dimensions of this important conflict, including detailed accounts of the air / sea battle, the Battle for San Carlos Water, Goose Green, Mt Harriet, Tumbledown and many others.

Men-at-Arms 133: Battle for the Falklands (1) Land Forces details the history, uniforms and equipment of the land forces that contested the Falklands War.

Men-at-Arms 134: Battle for the Falklands (2) Naval Forces examines the Argentine Marines and Royal Marines who fought in the battle for the Falklands.

Men-at-Arms 250: Argentine Forces in the Falklands examines the history, organization and equipment of the Argentine forces that battled for control of this remote British outpost.

Combat Aircraft 28: Air War in the Falklands 1982 shows how the key to British success was the speed with which the British gained and then maintained air superiority over the islands and the waters around them with their small force of Sea Harrier STOVL warplanes, which operated from two aircraft carriers.

No comments:

Post a Comment