https://ospreypublishing.com/thisweekhistory/

Sierżant Unii z 18. regimentu pieszego z Pensylwanii w mundurze polowym, uzbrojony w karabin kapiszonowy Enfield z bagnetem tulejkowym i rewolwer Smith & Wesson 2 wz. 1860

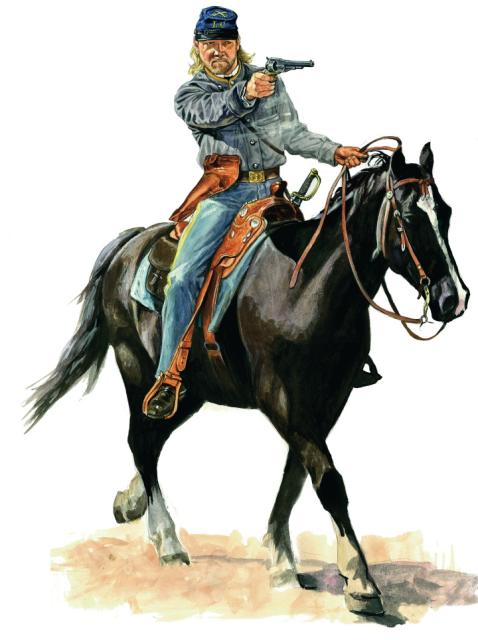

Konfederacki kawalerzysta z oddziału ochotników z Wirginii (London Cavarly) uzbrojony w rewolwer kapiszonowy Remington wz. 1858 kal. 44 i szablę M1850

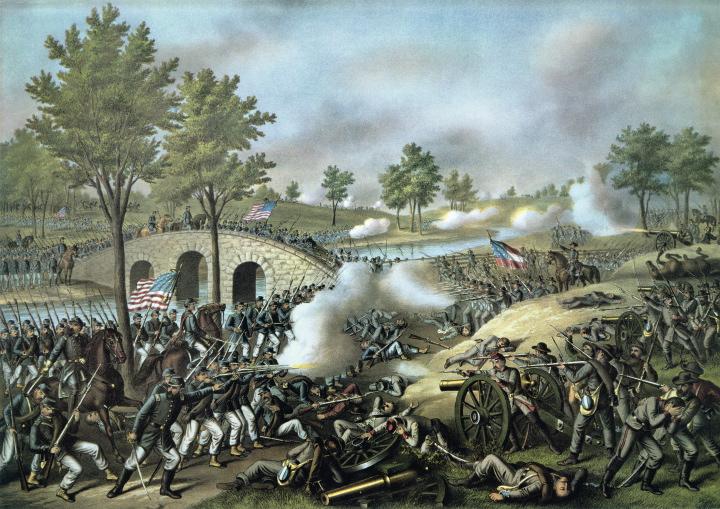

The Army of the Potomac under Joseph Hooker was threatening to cut off Lee's smaller Army of Northern Virginia from Richmond, the Confederate capital. Hooker had opened the campaign on 27 April with a strong move intended to bring Lee to battle and 'certain destruction'. Lee, however, forced him onto the defensive on 1 May and then planned a brilliant flanking move with Jackson; the latter executed this and crushed the Federal right on 2 May. That evening, however, Jackson was shot by his own pickets while reconnoitering to find a way to exploit the day's success further. He died on 10 May. The fighting continued on 3 May with Jeb Stuart ably taking over the command of II Corps from Jackson and concluded with Hooker's decision to retreat at the end of the following day.

Further Reading

Campaign 55: Chancellorsville 1863 (extract below) is a detailed account of the week's events and the build-up to the battle. Essential Histories Special 1: The American Civil War: This mighty scourge of war (extract below) places it in the full strategic context of the first half of the war in its eastern theater, also looking at it from political, social and individual perspectives. Warrior 60: Sharpshooters of the American Civil War 1861-65 reviews the training, fighting experience and weaponry of the marksman units developed by both sides from the start of the war. Elite 73: American Civil War Commanders (1) Union Leaders in the East and Elite 88: American Civil War Commanders (2) Confederate Leaders in the East(extract below) include portraits of the leading Union and Confederate generals who fought at Chancellorsville.

An Extract from Essential Histories Special 1: The American Civil War: This mighty scourge of war

An extract from Campaign 55: Chancellorsville 1863

Jackson attacks

An extract from Elite 88: American Civil War Commanders (2) Confederate Leaders in the East

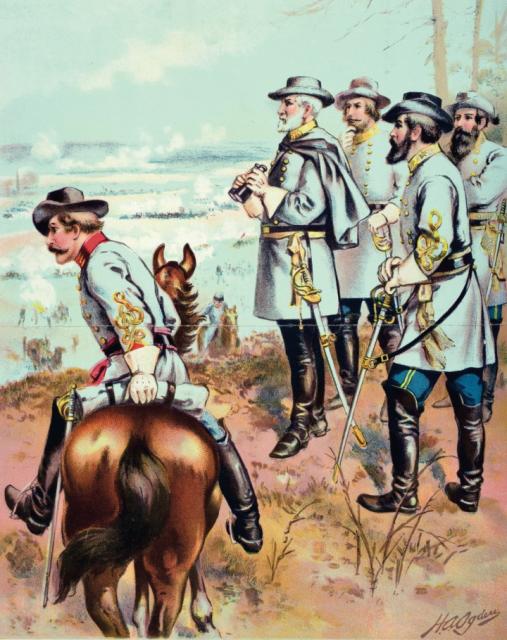

Stonewall

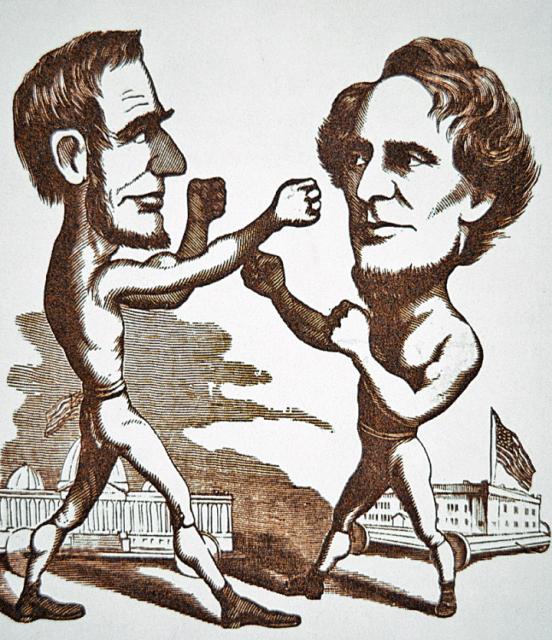

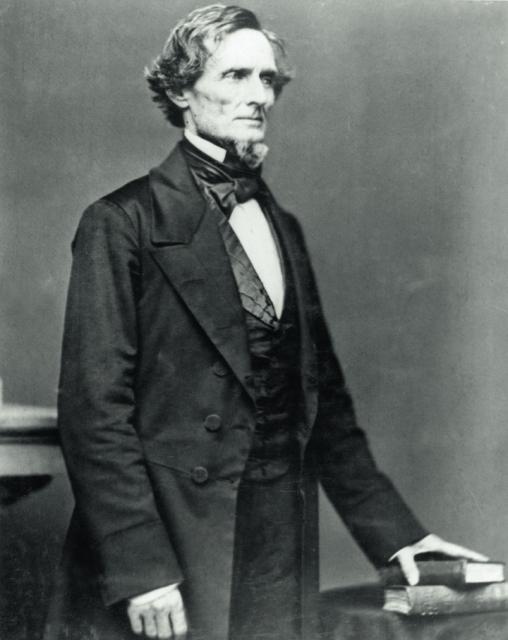

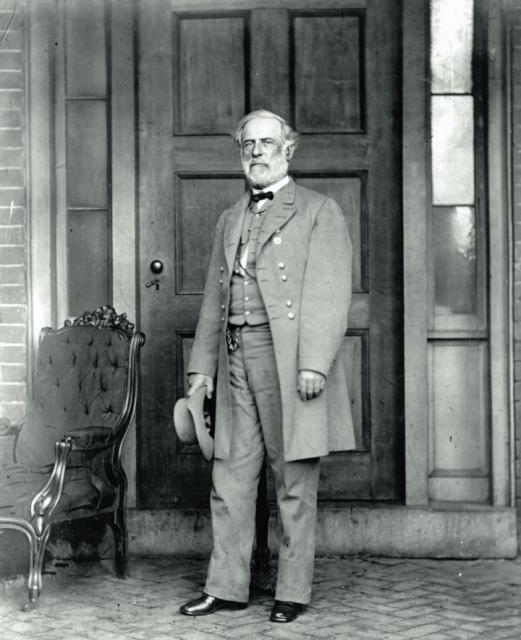

Prezydent Unii Abraham Lincoln walczy na pięści z prezydentem Konfederacji Jeffersonem Davisem, karykatura z czasów wojny secesyjnej Jefferson Davis, prezydent Konfederacji, fotografia z 1865 r. Gen. Robert E. Lee jako głównodowodzący wojsk Konfederacji, fotografia z 1865 r. Generał Robert E. Lee ze sztabem na polu bitwy, litografia H.A. Ogdena, początek XX w.

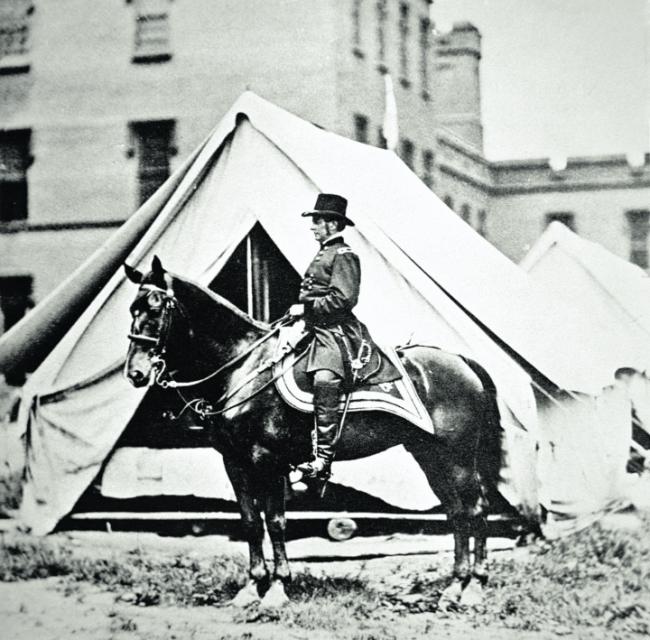

Generał Unii Joseph Hooker

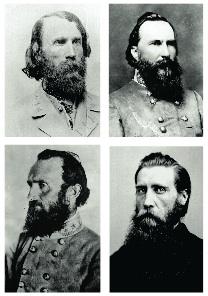

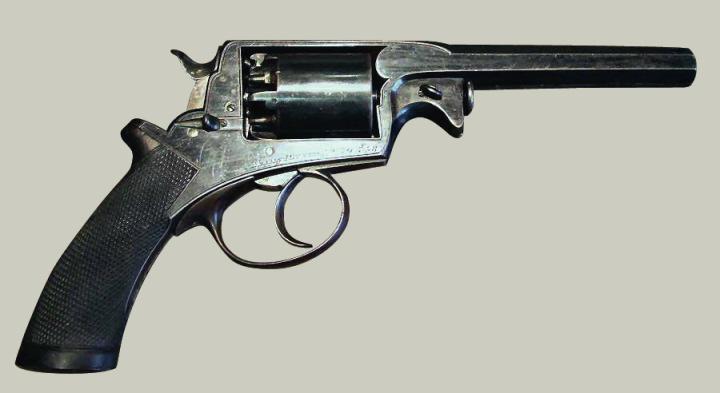

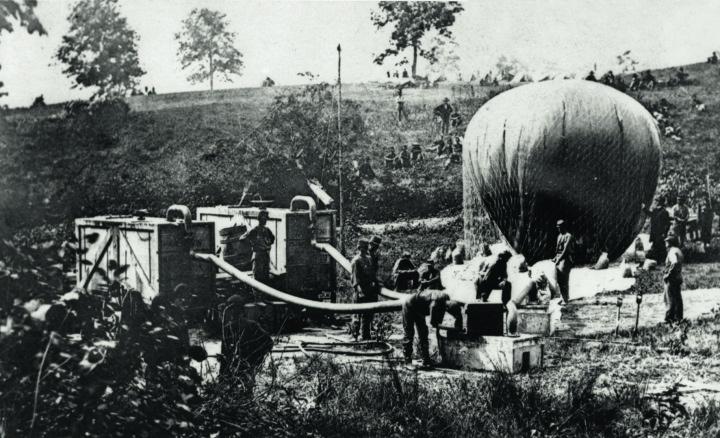

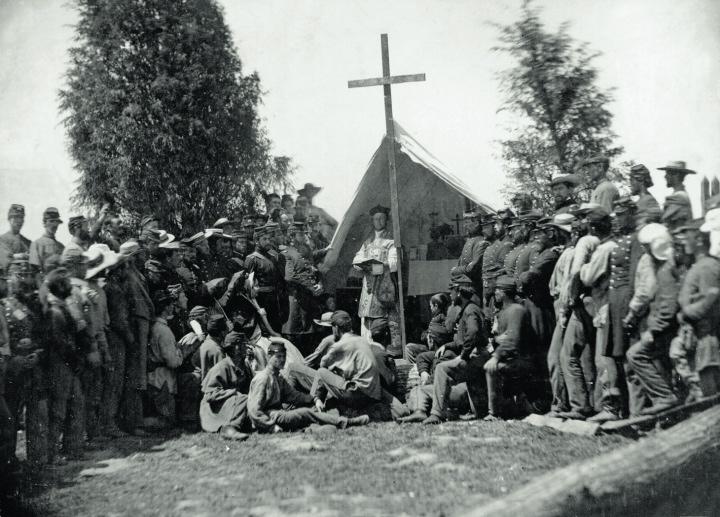

Dowódcy jednostek konfederackiej Armii Pólnocnej Wirginii (od góry): Ambrose Powell Hill, James Longstreet, Thomas Jonathan „Stonewall” Jackson, John Bell Hood Colt Army wz. 1860 Rewolwer Beaumont-Adams wz. 1854 używany przez konfederatów Colt Paterson wz. 1836, pierwsza konstrukcja Samuela Colta, która zyskała dużą popularność na rynku amerykańskim Kapiszonowe karabiny piechoty wz. 1861 używane przez żołnierzy Unii Szabla amerykańskiej kawalerii wz. 1840 Amerykańskie działo trzycalowe Ordnance Rifle Balon obserwacyjny wojsk Unii, czerwiec 1862 r. Fortyfikacje konfederatów podczas drugiej bitwy pod Bull Run, sierpień 1862 r. Grupa artylerzystów Unii z baterii Keystone Independent Light Artillery ≥>Ochotnicy z 69. regimentu nowojorskiego Prezydent Lincoln ze sztabem McClellana nad Antietam, 3 października 1862 r.

Sierżant Unii z 18. regimentu pieszego z Pensylwanii w mundurze polowym, uzbrojony w karabin kapiszonowy Enfield z bagnetem tulejkowym i rewolwer Smith & Wesson 2 wz. 1860

Sierżant kawalerii Unii - uzbrojony w szablę i karabin powtarzalny Spencera

|

Żołnierz Konfederacji uzbrojony w gwintowany, kapiszonowy karabin Springfield z bagnetem

The Army of the Potomac under Joseph Hooker was threatening to cut off Lee's smaller Army of Northern Virginia from Richmond, the Confederate capital. Hooker had opened the campaign on 27 April with a strong move intended to bring Lee to battle and 'certain destruction'. Lee, however, forced him onto the defensive on 1 May and then planned a brilliant flanking move with Jackson; the latter executed this and crushed the Federal right on 2 May. That evening, however, Jackson was shot by his own pickets while reconnoitering to find a way to exploit the day's success further. He died on 10 May. The fighting continued on 3 May with Jeb Stuart ably taking over the command of II Corps from Jackson and concluded with Hooker's decision to retreat at the end of the following day.

Further Reading

Campaign 55: Chancellorsville 1863 (extract below) is a detailed account of the week's events and the build-up to the battle. Essential Histories Special 1: The American Civil War: This mighty scourge of war (extract below) places it in the full strategic context of the first half of the war in its eastern theater, also looking at it from political, social and individual perspectives. Warrior 60: Sharpshooters of the American Civil War 1861-65 reviews the training, fighting experience and weaponry of the marksman units developed by both sides from the start of the war. Elite 73: American Civil War Commanders (1) Union Leaders in the East and Elite 88: American Civil War Commanders (2) Confederate Leaders in the East(extract below) include portraits of the leading Union and Confederate generals who fought at Chancellorsville.

An Extract from Essential Histories Special 1: The American Civil War: This mighty scourge of war

The strategic initiative rested with Hooker, who developed an impressive plan. He proposed holding Lee's attention at Fredericksburg with about 40,000 men under John Sedgwick, while several corps made a rapid march up the Rappahannock to turn the rebel left and get in Lee's rear. Most of the army's cavalry would ride towards Richmond, cutting Lee's lines of communication with the Confederate capital. The turning column would have to move through an area south of the Rappahannock and Rapidan rivers known as the Wilderness of Spotsylvania, approximately 70 square miles (180 square kilometres) of scrub woods and tangled undergrowth that would retard effective deployment of Hooker's superior manpower and artillery. Once in Lee's rear, a fast march towards Fredericksburg would take the Federals out of the Wilderness into open ground, where their numbers would tell. If all went well, Lee's army would be trapped between the flanking column and Sedgwick's force at Fredericksburg.

The campaign began brilliantly for the Federals. On 27 April 1863, Hooker's turning column swung up the Rappahannock, negotiated fords over the river and the Rapidan, and by early afternoon on the 30th reached the crossroads of Chancellorsville some 10 miles (16km) west of Fredericksburg. George G. Meade, who led the Union V Corps on the flanking manoeuvre, expressed unabashed enthusiasm at what Hooker has accomplished. 'This is splendid,' he said 'hurrah for old Joe; we are on Lee's flank, and he does not know it.' A march of 2 or 3 miles (about 4km) would take the Federals from Chancellorsville, which lay in the Wilderness, to clear ground further east. But Hooker ordered the troops to remain at Chancellorsville, where he joined them that evening. The Federal commander announced to his army that 'our enemy must either ingloriously fly, or come out from behind his defenses and give us battle on our own ground, where certain destruction awaits him.'

Lee reacted boldly to Hooker's manoeuvre. He divided his small army, leaving Jubal A. Early and about 10,000 men to watch Sedgwick at Fredericksburg and marching the other 50,000 to deal with the Federals at Chancellorsville. The critical moment of the campaign occurred on the morning of 1 May. Hooker's advancing infantry clashed with Confederates 3.5 miles (5.6km) east of Chancellorsville near Zoan Church, whereupon the Union commander ordered a withdrawal. Some of Hooker's subordinates argued vehemently for maintaining the offensive. A retreat into the gloomy Wilderness, they insisted, would negate all that had been accomplished over the past few days. But all offensive thoughts had left Hooker's mind, as he ordered his troops to concentrate and dig in near Chancellorsville. Darius N. Couch, leader of the Federal II Corps, bitterly concluded that 'my commanding general was a whipped man.'

Lee eagerly took the initiative. On the night of 1 May, he and Jackson discussed how best to attack Hooker. The Federal left occupied strong ground and rested near the Rappahannock. A frontal assault against Chancellorsville would be too costly. The best course seemed to be turning the Union right, which ran west from Chancellorsville along the Orange Plank Road and Orange Turnpike (the two main east-west arteries through the Wilderness). Lee decided to divide his army again, sending Jackson's Second Corps on a flank march along narrow country roads. Lee would keep the 14,000 men of Richard H. Anderson's and Layette McLaws's divisions of Longstreet's corps to occupy Hooker's attention.

Jackson conducted the war's most celebrated manoeuvre on 2 May, launching a powerful attack at about 5.15pm that crushed Oliver O. Howard's Union XI Corps. Many of Howard's troops were Germans, and critics later accused the 'damned Dutchmen' of fleeing without putting up a fight. In fact, no Union corps could have stood when Jackson's divisions swept out of the woods, shrieking the unnerving 'Rebel Yell' and easily overlapping every potential defensive position. Half the regimental commanders and a quarter of the soldiers in Howard's corps fell during the fighting - evidence that they offered considerable resistance.

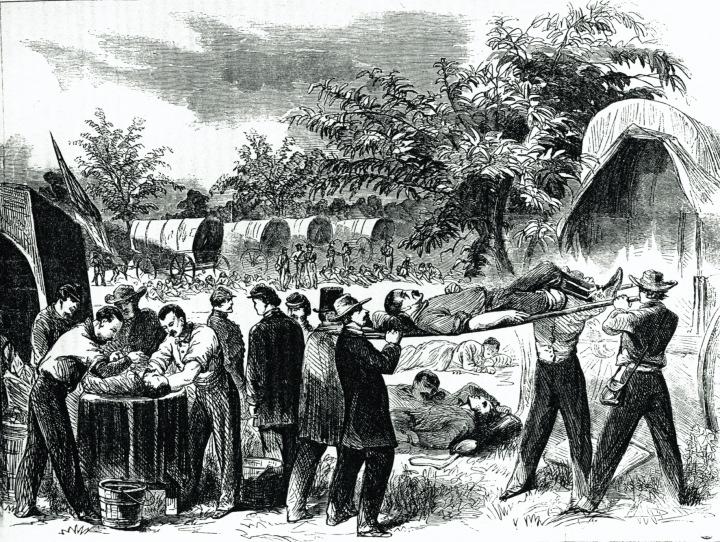

Darkness and confusion arising from the movement of large bodies of men through heavily wooded terrain slowed down the Confederate attack by about 7pm. Jackson hoped to reform and renew the attacks later that night. Riding to the front with the goal of finding a way to cut off Hooker from the Rappahannock fords, he rode into the path of a volley from a North Carolina regiment. Wounded in three places, he had his left arm amputated later that evening.

Despite Jackson's impressive attack, Lee's troops at Chancellorsville remained separated by Hooker's much larger force. Extremely hard fighting on the morning of 3 May enabled the Confederates to reunite their wings at Chancellorsville and push Hooker, who had been stunned when a southern artillery shell struck a pillar against which he was leaning, back closer to the Rappahannock. While a groggy Hooker sought to form a new defensive line, Lee guided Traveller, his sturdy gray warhorse, through thousands of Confederate infantrymen in a clearing near Chancellorsville. Emotions flowed freely as the soldiers, nearly 9,000 of whose comrades had fallen in the morning's fighting, shouted their devotion. Lee acknowledged their cheers by removing his hat. Seldom has the bond between a successful commander and his troops achieved more dramatic display. Colonel Charles Marshall of Lee's staff later wrote that Lee basked in 'the full realization of all that soldiers dream of - triumph,' adding: 'As I looked upon him in the complete fruition of the success which his genius, courage, and confidence in his army had won, I thought that it must have been from such a scene that men in ancient days rose to the dignity of gods.'

Within minutes Lee learned that Sedgwick had broken Early's line at Fredericksburg and was moving towards Chancellorsville. He divided his army for a third time, deploying about half his troops to block this new threat. A sharp action on 4 May at Salem Church, located some 4 miles (6.4km) west of Fredericksburg, stopped Sedgwick. That night Hooker decided to retreat, and by the morning of the 6th the Army of the Potomac had returned to the left bank of the Rappahannock.

Chancellorsville marked the apogee of Lee's career as a soldier and cemented the reciprocal trust between him and his men that made the Army of Northern Virginia so formidable. That trust radiated outwards to civilians in the Confederacy, who looked to Lee and his soldiers as their primary national rallying point from late 1862 onwards. Jefferson Davis gratefully thanked Lee 'in the name of the people ... for this addition to the unprecedented series of great victories which your army has achieved.' The success had come at a terrible cost. Among the 12,674 Confederate casualties was Stonewall Jackson, whose death on 10 May cast a pall over the Confederacy. Lee would never find an adequate replacement for the gifted lieutenant whom he called his 'right arm'.

On the Union side, Chancellorsville dealt a telling blow to hopes for victory. Once again a northern army superior in numbers and equipment had suffered agonizing defeat. Once again a Federal commander had failed to commit all his troops to battle (two of the Union corps had lost fewer than 1,000 men). The northern butcher's bill totalled 17,287. News of the defeat rocked Lincoln, who, while pacing back and forth moaned, 'My God! My God! What will the country say? What will the country say?' New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley rendered a common verdict: 'It is horrible - horrible; and to think of it, 130,000 magnificent soldiers so cut to pieces by less than 60,000 half-starved ragamuffins!'

Chancellorsville exacerbated deep divisions in the North. A recently passed National Conscription Act, Lincoln's final Emancipation Proclamation (which took effect on 1 January 1863) and other issues fuelled acrimonious debate. Hooker's failure increased unhappiness among northerners already disposed to criticize the Lincoln administration's conduct of the war. Even loyal Republicans wondered whether the rebels could be suppressed.

An extract from Campaign 55: Chancellorsville 1863

Jackson attacks

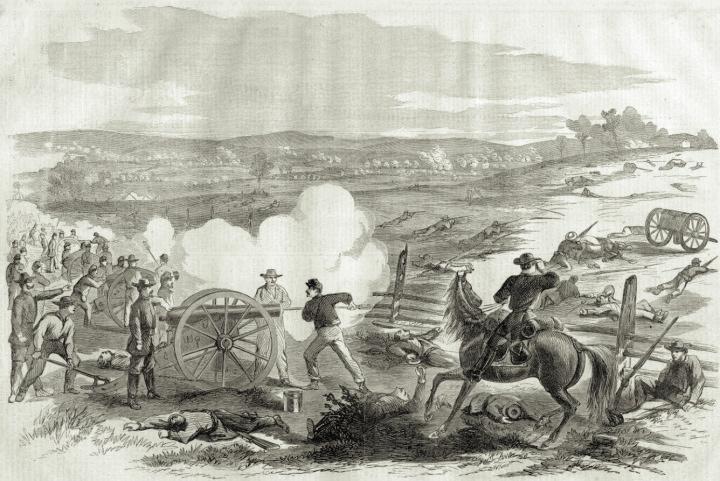

By 1700 that evening Jackson's men were in position far to the Union right of where Howard's XI Corps had lit their supper campfires. The evening sun was behind Jackson and would be in his enemy's eyes when he attacked. He deployed his division carefully along the turnpike: Rodes, followed by Colston, with A.P. Hill in the rear. Stuart's cavalry and the Stonewall brigade were to stick to the road and hold the Southern right flank. Colquitt, adjacent to Stuart, was told his flank was secure, and to ignore anything happening there, and not let it interfere with his advance as his flank was protected.

Jackson rode to the head of the column, aware of the eager eyes of the soldiers he passed. He moved alongside Rodes, saying, "You can go forward, sir." Rodes' division started east at a fast walk, rifles at low port, ready.

It was suppertime in the Union camp. Some troops were relaxing in their bedrolls, their muskets stacked, chatting with their messmates. These German-speaking troops had an imperfect command of English; they were comfortably seated around fires when the low howl of the rebel yell came from out of the sunset behind them.

From the trees to their west in the gathering gloom came an unearthly moan as ghostly gray shapes flitted toward them from the treeline. Musketry ripped into them. The Confederates changed from a fast walk to a charge, their weapons held higher, eyes hard, screaming a rebel yell. The Union soldiers were stunned. Before they could form a defensive position, indeed before many could grab weapons, Jackson's foot cavalry was among them.

Von Gilsa's 54th NY and 153rd PA faced the Confederate charge, firing into the oncoming Southerners. The 41st and 45th NY were totally surprised by the flanking movement. They broke and ran without fighting as the Confederates rolled up their flank. Dieckmann's two guns fired, but before they could reload, musketry downed their horses and they had to abandon the guns. The 54th NY broke before the charging Confederates, and the fledgling 153rd PA faced the Georgians alone. Then they broke. The charge washed over Von Gilsa's positions, hitting Devens' flank. In minutes Von Gilsa lost 264 men, including half his regimental commanders.

Confusion in the woods was complete. The Confederates were supposed to be to their front, and here they were being hit from the right flank in thick woods at twilight when friend and foe were both gray shapes against the dark woods.

An extract from Elite 88: American Civil War Commanders (2) Confederate Leaders in the East

Stonewall

"Stonewall" Jackson was born in Clarksburg, now in West Virginia, on 21 January 1824. Poorly educated, he was still graduated 17th in the West Point class of 1846. Commissioned into the 1st US Artillery Regiment, he distinguished himself in the Mexican War, being breveted captain on 20 August 1847 "for gallant and meritorious conduct during the Battles of Contreras and Churubusco." He was named brevet major on 13 September for his conduct at Chapultepec. Jackson resigned from the US Army on 29 February 1852 to take up a teaching position at the Virginia Military Institute. He also instructed African-American children at his local Presbyterian Church, of which he was a devout member. A Virginia militia colonel, he was named to command at Harper's Ferry at the outbreak of the Civil War.

Jackson was named brigadier-general on 17 June 1861, and took his 1st Brigade to First Manassas (Bull Run, 21 July), where his determined stand gained him - and his brigade - the nickname of "Stonewall" by which he has become known to history. Appointed major-general on 7 August, he was sent to West Virginia, but his poorly supplied troops failed to hold that part of the state. He was then sent to clear the strategic Shenandoah Valley of Virginia of Union forces, and to divert troops from McClellan's army threatening Richmond. He demonstrated brilliant generalship in achieving this task; in his electrifying campaign of May-June 1862 his 18,000 men baffled, defeated, and tied down some 70,000 Federal troops by means of rapid marches and counter-marches. With the Valley now free, his forces were recalled to the defense of Richmond; but Jackson performed poorly in the Seven Days' Battles of June-July, and some believe that his lackluster performance was due to fatigue.

With Richmond safe for the time being, Jackson went north to stop a new Union Army of Virginia in its drive on the city, and his turning movement in August 1862 was the key to the victory of Second Manassas that followed on 29-30 August. In the subsequent Confederate invasion of Maryland he first captured Harper's Ferry, then sped to join Lee at Sharpsburg (Antietam), where his stubborn defense was central in saving the Army of Northern Virginia. Named lieutenant-general in command of II Corps on 10 October 1862, Jackson commanded the right wing at Fredericksburg on 13 December.

At Chancellorsville, Jackson suggested the flank movement that would smash the Union Army. On the night of 2 May 1863, while reconnoitering at Chancellorsville between two front-line North Carolina regiments, he was shot by jittery Confederate sentries. His left arm was amputated, but pneumonia developed and he died on 10 May. After lying in state in Richmond, he was buried in Lexington, Virginia.

Charles Blackford, 2nd Virginia Cavalry, wrote home: "No one seems to know much of him, not even those who are with him hourly. He has no social graces but infinite earnestness. He belongs to the class from which Cromwell's regiment was made except he has no religious hypocrisy about him. He is a zealot and has stern ideas of duty." His men, noting this, called him at first "Tom Fool Jack," and later "Old Bluelight," as well as "Stonewall." Nevertheless, Kyd Douglas of his staff wrote: "He did not live apart from his personal staff, although they were nearly all young; he liked to have them about, especially at the table. He encouraged the liveliness of their conversations at meals, although he took little part in it as he never told his plans, he never discussed them." Jackson was concerned about his diet: Kyd Douglas recalled, "Whatever might be the variety before him the general selected one or two things only for his meal and ate of them abundantly. He seemed to know what agreed with him, and often puzzled others by his selections. I knew him to make a very hearty dinner of raspberries, milk and bread."

Later Blackford wrote: "He is ever monosyllabic and receives and delivers a message as if the bearer was a conduct pipe from one ear to another. There is a magnetism in Jackson, but it is not personal. All admire his genius and great deeds; no one could love the man for himself. He seems to be cut off from his fellow men and to commune with his own spirit only, or with spirits of which we know not." Perhaps this is why he was generally a poor judge of character, although he could certainly read an enemy's intentions.

The British military observer Arthur Fremantle wrote that Joseph E.Johnston had said of Jackson that he "did not possess any great qualifications as a strategist, and was perhaps unfit for the independent command of a large army, yet he was gifted with wonderful courage and determination, and a perfect faith in Providence that he was destined to destroy the enemy." E.Porter Alexander felt that this faith was actually a defect: "He believed, with absolute faith, in a personal God, watching all human events with a jealous eye to His own glory - ready to reward those people who made it their chief care, & to punish those who forgot about it."

Prezydent Unii Abraham Lincoln walczy na pięści z prezydentem Konfederacji Jeffersonem Davisem, karykatura z czasów wojny secesyjnej Jefferson Davis, prezydent Konfederacji, fotografia z 1865 r. Gen. Robert E. Lee jako głównodowodzący wojsk Konfederacji, fotografia z 1865 r. Generał Robert E. Lee ze sztabem na polu bitwy, litografia H.A. Ogdena, początek XX w.

Generał Unii Joseph Hooker

Dowódcy jednostek konfederackiej Armii Pólnocnej Wirginii (od góry): Ambrose Powell Hill, James Longstreet, Thomas Jonathan „Stonewall” Jackson, John Bell Hood Colt Army wz. 1860 Rewolwer Beaumont-Adams wz. 1854 używany przez konfederatów Colt Paterson wz. 1836, pierwsza konstrukcja Samuela Colta, która zyskała dużą popularność na rynku amerykańskim Kapiszonowe karabiny piechoty wz. 1861 używane przez żołnierzy Unii Szabla amerykańskiej kawalerii wz. 1840 Amerykańskie działo trzycalowe Ordnance Rifle Balon obserwacyjny wojsk Unii, czerwiec 1862 r. Fortyfikacje konfederatów podczas drugiej bitwy pod Bull Run, sierpień 1862 r. Grupa artylerzystów Unii z baterii Keystone Independent Light Artillery ≥>Ochotnicy z 69. regimentu nowojorskiego Prezydent Lincoln ze sztabem McClellana nad Antietam, 3 października 1862 r.

No comments:

Post a Comment