https://ospreypublishing.com/thisweekhistory/

8 May 1945 is one of the most famous dates in modern history. It is Victory in Europe Day, the day that the Germans finally surrendered to the Allies, on both the Western and Eastern Fronts, and the war in Europe finally ended. World War II, however, was far from over, and fighting in the Pacific continued until the Japanese officially surrendered on 2 September 1945, following the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki

An Extract from Essential Histories Specials 3: The Second World War: A World in Flames

The road to VE day

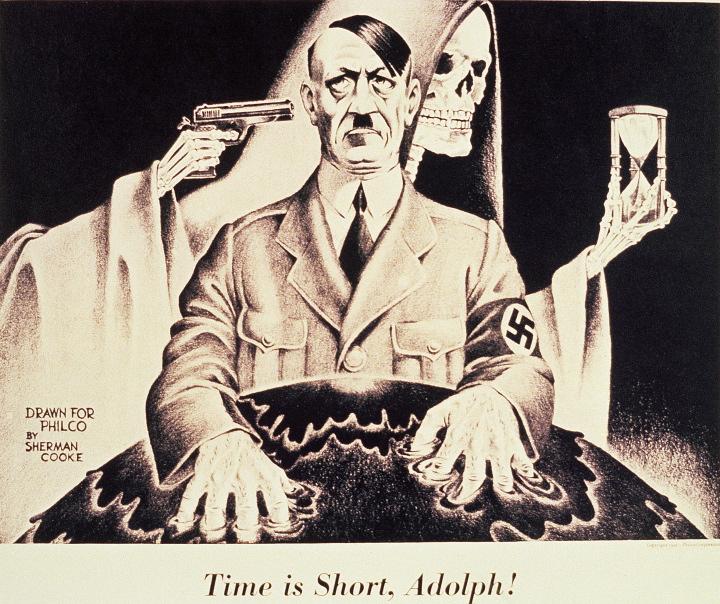

The key event that made possible the end of the northwest Europe campaign – and the entire Second World War in Europe – occurred at 3.30 pm on 30 April 1945. At that moment, the German Führer, Adolf Hitler, committed suicide in the Reichschancellory Bunker in Berlin, as above ground triumphant Soviet forces advanced to within 330yds/300m of this installation. Back on 22 April, as Soviet spearheads began to encircle the German capital, Hitler had abandoned his notion of escaping to lead Germany’s war from Berchtesgaden in Bavaria, and instead decided to remain in Berlin to meet his fate.

Even into the last hours of his life, Hitler remained determined that Germany would continue its desperate resistance against the Allied advance, if necessary to the last man and round, irrespective of the destruction that this would inflict on the German nation. With the Führer’s death, so passed away this iron resolve to prosecute to the last a war that almost every German now recognized as already lost. On 30 April, though, Hitler ordered that, once he had taken his own life, Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz, Commander-in-Chief of the Navy, should replace him as Führer. His successor, Hitler instructed, was to continue Germany’s resistance to the Allies for as long as possible, irrespective of the cost.

Yet even before the Führer’s suicide, it seemed to him that several rats had already attempted to desert the sinking Nazi ship. On 23 April, for example, Hitler’s designated deputy, Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, had informed Hitler – now surrounded in Berlin, but very much alive – that as the latter had lost his freedom of action, the Reichsmarschall would assume the office of Führer. An enraged Hitler, interpreting this as treason, relieved Göring of his offices and ordered his arrest.

The day before, Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler had secretly met Count Folke Bernadotte of Sweden at Lübeck. At this meeting, Himmler offered to surrender all German armies facing the Western Allies, allowing the latter to advance east to prevent more German territory falling to the Soviets. The Reichsführer hoped that his offer would entice the Western Allies into continuing the war that Germany had waged since 1941 against the Soviet Union – the common enemy of all the states of Europe, Himmler believed. The Western Allies, however, remained committed to accept nothing other than Germany’s simultaneous unconditional surrender to the four major Allied powers. Moreover, they recognized Himmler’s diplomatic approach as nothing more than a crude attempt to split their alliance with the Soviets, and so rejected Himmler’s offer on 27 April. When Hitler heard of Himmler’s treachery on 28 April, he ordered that his erstwhile ‘Loyal Heinrich’ be arrested.

Simultaneously, and with Himmler’s connivance, SS Colonel-General Karl Wolff, the German military governor of northern Italy, continued the secret negotiations that he had initiated with the Western Allies in February 1945 over the surrender of the German forces deployed in Italy. On 29 April – the day before Hitler’s suicide – in another vain attempt to split the Allied alliance, a representative of General von Vietinghoff signed the instrument of surrender for the German forces located in Italy. By 2 May, some 300,000 German troops in this area had already laid down their arms.

On 1 May 1945, the new Führer, Karl Dönitz, established his headquarters at Flensburg near the German–Danish border in Schleswig-Holstein. Dönitz immediately abandoned Hitler’s futile mantra of offering resistance to the last bullet, and accepted that the war was lost. Instead, Dönitz attempted merely to continue the war to save what could reasonably be rescued from the Soviets’ grasp. By surrendering German forces piecemeal in the west, Dönitz hoped that the Western Allies would occupy most of the Reich to spare the bulk of the German nation from the horrors of Soviet occupation. Furthermore, when the advancing Western Allies neared the rear lines of the German forces still locked in bitter resistance against the Soviets in the east, Dönitz hoped to withdraw these troops – plus the isolated garrisons of East Prussia and Courland – into Western Allied captivity. In this fashion, Dönitz hoped to save the bulk of the German army in the east from the nightmare of years of forced labor in Stalin’s infamous prison camps.

But during 1–2 May 1945, Germany’s already dire strategic situation deteriorated further, undermining Dönitz’s strategy of calculated delaying actions. In that period, Montgomery’s forces cut off Schleswig-Holstein from Germany by linking up with the Red Army on the Baltic coast, while the Americans consolidated their link-up with the Soviets in central Germany. Although on 3 May the German army could still field over five million troops, it was obvious to all that within a few days the Allies would overrun what little remained of Hitler’s supposed Thousand-Year Reich.

Given these harsh realities, on the morning of Thursday 3 May, Dönitz sent a delegation under a flag of truce to Montgomery’s new tactical headquarters on the windswept Lüneberg Heath. The delegation wished to negotiate the surrender to Montgomery of not just the German forces that faced the 21st Army Group but also the three German armies of Army Group Vistula then resisting the Soviets in Mecklenburg and Brandenburg.

Montgomery stated that he would accept the surrender of all German forces that faced him in northwestern Germany and Denmark, but could not accept that of those facing the Red Army, who had to surrender to the Soviets. If the Germans did not immediately surrender, Montgomery brutally warned, his forces would continue their attacks until all the German soldiers facing him had been killed. Montgomery’s stance shattered the German negotiators’ flimsy hopes of securing, at least in this region, a salvation from looming Soviet captivity. Disheartened, they returned to Flensburg to discuss their response with Dönitz and German Armed Forces Commander-in-Chief Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel.

The Germans arrived back at Montgomery’s headquarters on the afternoon of Friday 4 May. At 6.30 pm in an inconspicuous canvas tent, on a standard army table covered with a rough blanket for this momentous occasion, Grand Admiral Hans von Friedeberg signed an instrument of surrender. By this instrument he capitulated to the British the 1.7 million German troops who faced Montgomery’s forces in northwestern Germany and Denmark, with effect from 8.00 am on 5 May. In his moment of triumph, a gloating Montgomery entered the wrong date on the historic surrender document, and had to initial his amendment.

After this surrender, the Western Allies still had to resolve the issue of the capitulation of the remaining German forces deployed along the Western Front. During 5 May, and into the next morning, the negotiating German officers dragged their feet to buy time for German units then still fighting the Soviets to retreat west in small groups to enter Western Allied captivity. Meanwhile, on the afternoon of 5 May, General von Blaskowitz surrendered the encircled German forces in northwestern Holland to the Canadian army, while on the next day, the German Army Group G deployed in western Austria capitulated to the Americans.

Then, on 6 May, Colonel-General Alfred Jodl, Chief of the Armed Forces Operations Staff, flew from Flensburg to Supreme Allied Commander Dwight Eisenhower’s headquarters at Rheims, where the latter expected him to sign the immediate unconditional surrender of all remaining German forces to the four Allied powers. Initially, Jodl tried to negotiate only the surrender of those German forces still facing west, excluding those on the Eastern Front. In response, Eisenhower threatened to abandon the negotiations and close the Western Front to all Germans soldiers attempting to surrender, unless Jodl immediately agreed to the unconditional surrender of all Germans forces in all theaters. Jodl radioed Dönitz for instructions, and received his reluctant permission to sign. At 2.41 am on 7 May 1945, Jodl signed the instrument of surrender, which was slated to take effect on 8 May at 11.01 pm British Standard Time. The Germans used the remaining 44 hours before the Second World War in Europe officially ended to withdraw as many forces as possible from the east and surrender them to the Western Allies.

Finally, in Berlin at 11.30 pm on 8 May, after the cessation of hostilities deadline had passed, von Friedeberg and Keitel again signed the instrument of surrender concluded at Rheims the previous morning to confirm the laying down of German arms. Officially, the Second World War in Europe was over. Dönitz’s government continued to function until 23 May, when it was dissolved and the second Führer arrested. Subsequently, the Nuremberg War Crimes Tribunal sentenced Dönitz to 10 years’ imprisonment. Despite the official German surrender on 8 May, though, many German units in the east continued to resist the Soviets during the next few days. Indeed, the very last German forces did not surrender until 15 May 1945, a full week after Germany’s official surrender. But by this date, it is fair to say that both the 1944–45 northwest Europe campaign, and the entire Second World War in Europe, had finally ended.

8 May 1945 is one of the most famous dates in modern history. It is Victory in Europe Day, the day that the Germans finally surrendered to the Allies, on both the Western and Eastern Fronts, and the war in Europe finally ended. World War II, however, was far from over, and fighting in the Pacific continued until the Japanese officially surrendered on 2 September 1945, following the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki

An Extract from Essential Histories Specials 3: The Second World War: A World in Flames

The road to VE day

The key event that made possible the end of the northwest Europe campaign – and the entire Second World War in Europe – occurred at 3.30 pm on 30 April 1945. At that moment, the German Führer, Adolf Hitler, committed suicide in the Reichschancellory Bunker in Berlin, as above ground triumphant Soviet forces advanced to within 330yds/300m of this installation. Back on 22 April, as Soviet spearheads began to encircle the German capital, Hitler had abandoned his notion of escaping to lead Germany’s war from Berchtesgaden in Bavaria, and instead decided to remain in Berlin to meet his fate.

Even into the last hours of his life, Hitler remained determined that Germany would continue its desperate resistance against the Allied advance, if necessary to the last man and round, irrespective of the destruction that this would inflict on the German nation. With the Führer’s death, so passed away this iron resolve to prosecute to the last a war that almost every German now recognized as already lost. On 30 April, though, Hitler ordered that, once he had taken his own life, Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz, Commander-in-Chief of the Navy, should replace him as Führer. His successor, Hitler instructed, was to continue Germany’s resistance to the Allies for as long as possible, irrespective of the cost.

Yet even before the Führer’s suicide, it seemed to him that several rats had already attempted to desert the sinking Nazi ship. On 23 April, for example, Hitler’s designated deputy, Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, had informed Hitler – now surrounded in Berlin, but very much alive – that as the latter had lost his freedom of action, the Reichsmarschall would assume the office of Führer. An enraged Hitler, interpreting this as treason, relieved Göring of his offices and ordered his arrest.

The day before, Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler had secretly met Count Folke Bernadotte of Sweden at Lübeck. At this meeting, Himmler offered to surrender all German armies facing the Western Allies, allowing the latter to advance east to prevent more German territory falling to the Soviets. The Reichsführer hoped that his offer would entice the Western Allies into continuing the war that Germany had waged since 1941 against the Soviet Union – the common enemy of all the states of Europe, Himmler believed. The Western Allies, however, remained committed to accept nothing other than Germany’s simultaneous unconditional surrender to the four major Allied powers. Moreover, they recognized Himmler’s diplomatic approach as nothing more than a crude attempt to split their alliance with the Soviets, and so rejected Himmler’s offer on 27 April. When Hitler heard of Himmler’s treachery on 28 April, he ordered that his erstwhile ‘Loyal Heinrich’ be arrested.

Simultaneously, and with Himmler’s connivance, SS Colonel-General Karl Wolff, the German military governor of northern Italy, continued the secret negotiations that he had initiated with the Western Allies in February 1945 over the surrender of the German forces deployed in Italy. On 29 April – the day before Hitler’s suicide – in another vain attempt to split the Allied alliance, a representative of General von Vietinghoff signed the instrument of surrender for the German forces located in Italy. By 2 May, some 300,000 German troops in this area had already laid down their arms.

On 1 May 1945, the new Führer, Karl Dönitz, established his headquarters at Flensburg near the German–Danish border in Schleswig-Holstein. Dönitz immediately abandoned Hitler’s futile mantra of offering resistance to the last bullet, and accepted that the war was lost. Instead, Dönitz attempted merely to continue the war to save what could reasonably be rescued from the Soviets’ grasp. By surrendering German forces piecemeal in the west, Dönitz hoped that the Western Allies would occupy most of the Reich to spare the bulk of the German nation from the horrors of Soviet occupation. Furthermore, when the advancing Western Allies neared the rear lines of the German forces still locked in bitter resistance against the Soviets in the east, Dönitz hoped to withdraw these troops – plus the isolated garrisons of East Prussia and Courland – into Western Allied captivity. In this fashion, Dönitz hoped to save the bulk of the German army in the east from the nightmare of years of forced labor in Stalin’s infamous prison camps.

But during 1–2 May 1945, Germany’s already dire strategic situation deteriorated further, undermining Dönitz’s strategy of calculated delaying actions. In that period, Montgomery’s forces cut off Schleswig-Holstein from Germany by linking up with the Red Army on the Baltic coast, while the Americans consolidated their link-up with the Soviets in central Germany. Although on 3 May the German army could still field over five million troops, it was obvious to all that within a few days the Allies would overrun what little remained of Hitler’s supposed Thousand-Year Reich.

Given these harsh realities, on the morning of Thursday 3 May, Dönitz sent a delegation under a flag of truce to Montgomery’s new tactical headquarters on the windswept Lüneberg Heath. The delegation wished to negotiate the surrender to Montgomery of not just the German forces that faced the 21st Army Group but also the three German armies of Army Group Vistula then resisting the Soviets in Mecklenburg and Brandenburg.

Montgomery stated that he would accept the surrender of all German forces that faced him in northwestern Germany and Denmark, but could not accept that of those facing the Red Army, who had to surrender to the Soviets. If the Germans did not immediately surrender, Montgomery brutally warned, his forces would continue their attacks until all the German soldiers facing him had been killed. Montgomery’s stance shattered the German negotiators’ flimsy hopes of securing, at least in this region, a salvation from looming Soviet captivity. Disheartened, they returned to Flensburg to discuss their response with Dönitz and German Armed Forces Commander-in-Chief Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel.

The Germans arrived back at Montgomery’s headquarters on the afternoon of Friday 4 May. At 6.30 pm in an inconspicuous canvas tent, on a standard army table covered with a rough blanket for this momentous occasion, Grand Admiral Hans von Friedeberg signed an instrument of surrender. By this instrument he capitulated to the British the 1.7 million German troops who faced Montgomery’s forces in northwestern Germany and Denmark, with effect from 8.00 am on 5 May. In his moment of triumph, a gloating Montgomery entered the wrong date on the historic surrender document, and had to initial his amendment.

After this surrender, the Western Allies still had to resolve the issue of the capitulation of the remaining German forces deployed along the Western Front. During 5 May, and into the next morning, the negotiating German officers dragged their feet to buy time for German units then still fighting the Soviets to retreat west in small groups to enter Western Allied captivity. Meanwhile, on the afternoon of 5 May, General von Blaskowitz surrendered the encircled German forces in northwestern Holland to the Canadian army, while on the next day, the German Army Group G deployed in western Austria capitulated to the Americans.

Then, on 6 May, Colonel-General Alfred Jodl, Chief of the Armed Forces Operations Staff, flew from Flensburg to Supreme Allied Commander Dwight Eisenhower’s headquarters at Rheims, where the latter expected him to sign the immediate unconditional surrender of all remaining German forces to the four Allied powers. Initially, Jodl tried to negotiate only the surrender of those German forces still facing west, excluding those on the Eastern Front. In response, Eisenhower threatened to abandon the negotiations and close the Western Front to all Germans soldiers attempting to surrender, unless Jodl immediately agreed to the unconditional surrender of all Germans forces in all theaters. Jodl radioed Dönitz for instructions, and received his reluctant permission to sign. At 2.41 am on 7 May 1945, Jodl signed the instrument of surrender, which was slated to take effect on 8 May at 11.01 pm British Standard Time. The Germans used the remaining 44 hours before the Second World War in Europe officially ended to withdraw as many forces as possible from the east and surrender them to the Western Allies.

Finally, in Berlin at 11.30 pm on 8 May, after the cessation of hostilities deadline had passed, von Friedeberg and Keitel again signed the instrument of surrender concluded at Rheims the previous morning to confirm the laying down of German arms. Officially, the Second World War in Europe was over. Dönitz’s government continued to function until 23 May, when it was dissolved and the second Führer arrested. Subsequently, the Nuremberg War Crimes Tribunal sentenced Dönitz to 10 years’ imprisonment. Despite the official German surrender on 8 May, though, many German units in the east continued to resist the Soviets during the next few days. Indeed, the very last German forces did not surrender until 15 May 1945, a full week after Germany’s official surrender. But by this date, it is fair to say that both the 1944–45 northwest Europe campaign, and the entire Second World War in Europe, had finally ended.

No comments:

Post a Comment