https://ospreypublishing.com/thisweekhistory/

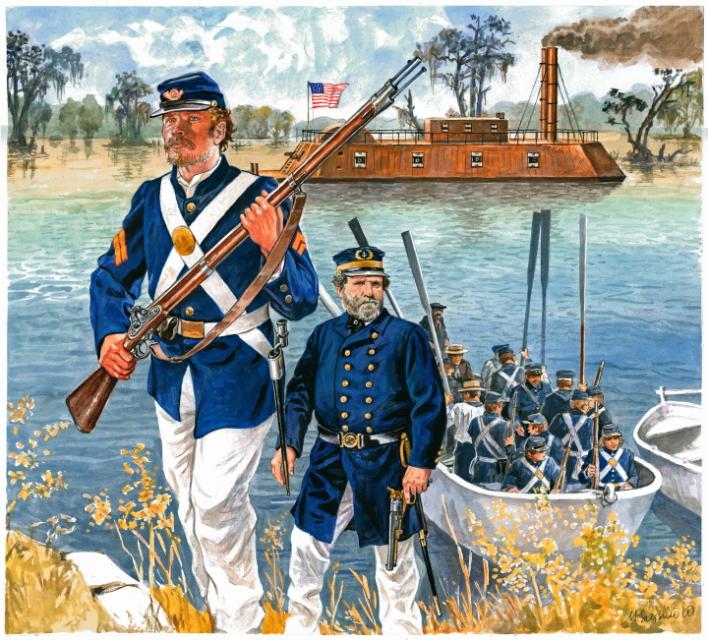

Admirał Farragut podczas bitwy w zatoce Mobile, 5 sierpnia 1864 r., mal. Henry A. Ogden

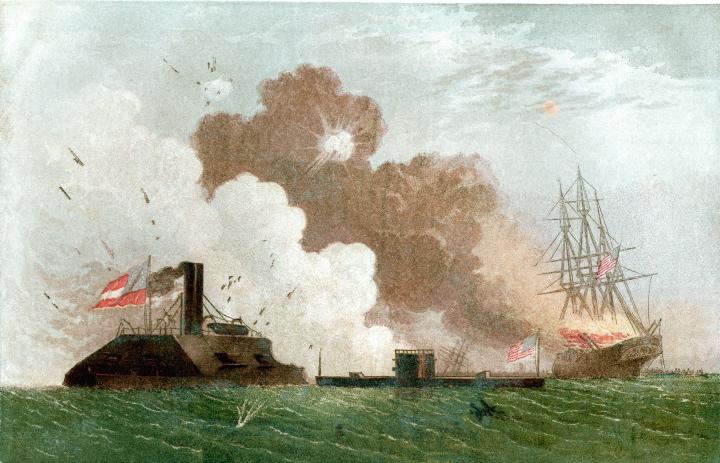

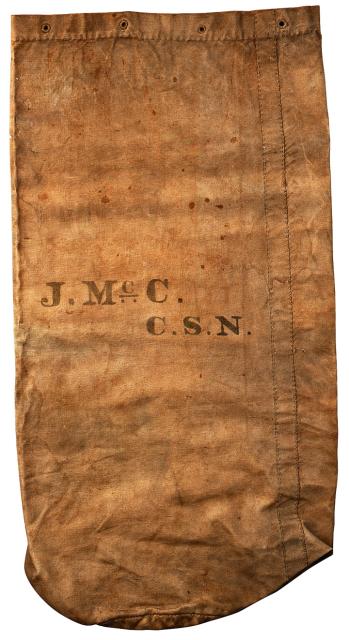

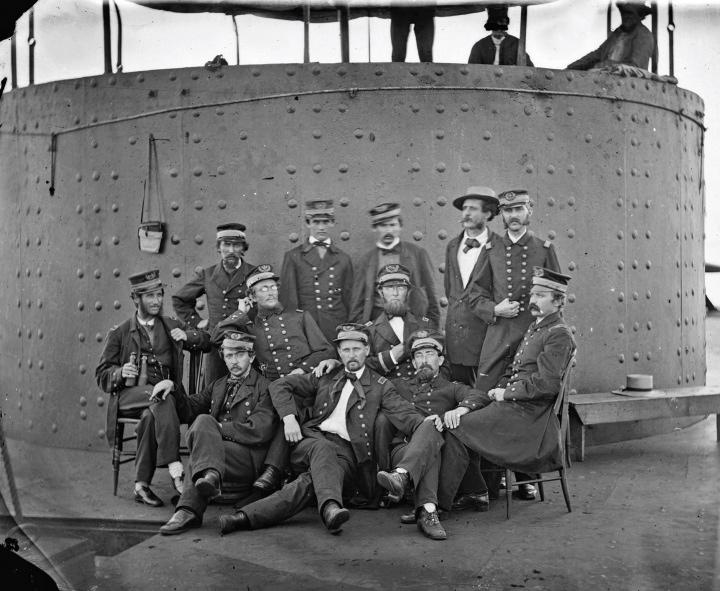

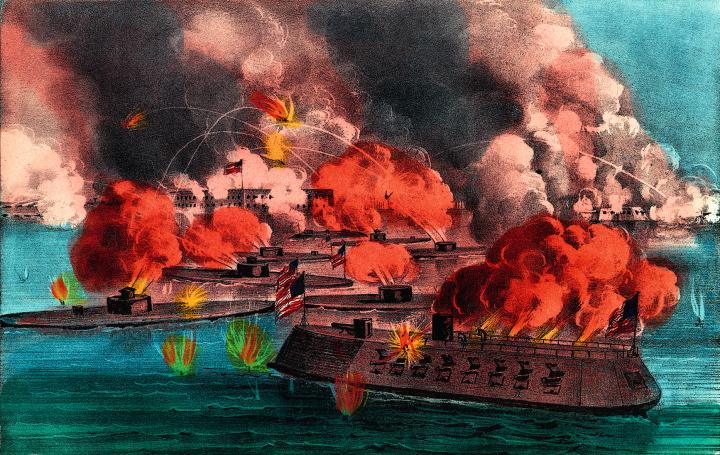

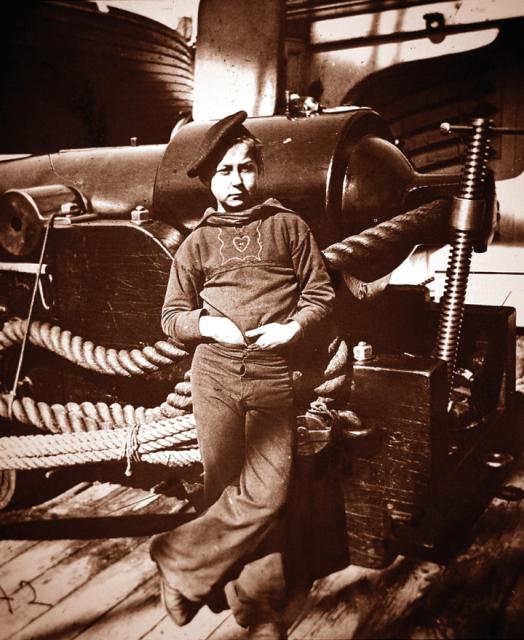

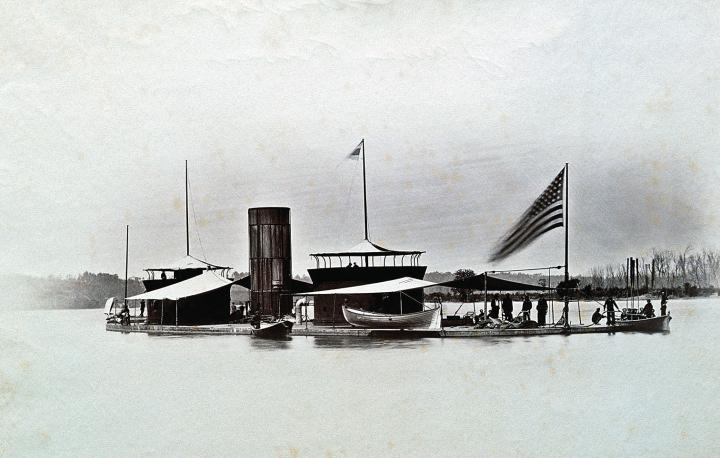

Kurtka mundurowa podporucznika marynarki Unii Kepi artylerzysty US „Navy” z czasów wojny secesyjnej Torba marynarza floty konfederackiej z czasów wojny secesyjnej Konfederacki kordelas marynarski, lata 60. XIX w. Oficerowie USS „Monitor”, lipiec 1862 r. Okręty pancerne Unii ostrzeliwują baterię konfederatów w Charleston, kwiecień 1863 r. Okręty pancerne Unii ostrzeliwują pozycje konfederatów nad rzeką Missisipi, 1862 r. Powder monkey – chłopiec okrętowy na pokładzie okrętu Unii Okręt pancerny USS „Onondaga” w zatoce na rzece James, 1862 r.

An extract from New Vanguard 49: Mississippi River Gunboats of the American Civil War 1861-65

The battle of Memphis

On May 10, 1862, the Union river fleet was above Fort Pillow, providing cover for mortar boats which were bombarding the Confederate positions. The vessel on point guard furthest downstream was the casemate ironclad USS Cincinnati. Smoke was spotted, and as the ironclad raised steam, Captain James E. Montgomery's River Defense Fleet rounded the bend. Montgomery commanded his full flotilla of eight rams, and led the way in his flagship, CSS Little Rebel. His vessels were making approximately nine knots, steaming against a one-knot current. The Confederates had the advantage of surprise, and before the Cincinnati could get fully under way the CSS General Bragg rammed her on her starboard side. The Cincinnati replied with a broadside at point-blank range, sending the large wooden ram reeling downstream. Just then the CSS General Sterling Price

smashed into the ironclad's stern, disabling her rudder.

By this time other ironclads had entered the fight, and the USS Carondolet

and the USS Mound City poured fire into the General Bragg, which drifted away, out of the fight. The CSS General Sumter was the next vessel to smash into the Cincinnati , causing severe damage. The leading mortar boat fired mortar shells over the Sumter to prevent sharpshooters on her decks firing into the ironclad. The CSS General Van Dorn replied by firing two 32-pounder shells into the mortar boat, disabling it completely. The ram then steamed past and rammed the Mound City, just seconds after the ironclad was rammed by the Sumter. The ironclad limped off, and sank in shallow water. Next, the ironclad USS Benton arrived and fired on the CSS Colonel Lovell, while the Carondolet

hit the Sumter's boiler, which exploded, causing heavy casualties.

Faced with annihilation, Montgomery withdrew the remainder of his force. As he now faced the entire Union river ironclad fleet, he had little option. As the Benton and Carondolet

gave chase, the Cincinnati sank in 11 feet of water, the last casualty of the battle. In an engagement that had only lasted about 40 minutes, two Union ironclads had been sunk for the loss of 108 men, and in return for heavy damage to three Confederate rams. Once more the effectiveness of ramming tactics had been demonstrated, this time against an armored opponent. Although what became known as the Battle of Plum Point was a Confederate victory, Montgomery could ill afford such losses, and both Union ironclads were raised and repaired. Next time the two fleets met, the North would have rams of their own.

On June 6, 1862, the two fleets met again off Memphis in a dawn battle, watched by numerous onlookers on the shore. Once again, the Confederates fielded eight vessels, as the extensive damage to the ram fleet had been repaired. Five Union ironclads came downriver stern first, followed by five wooden Ellet rams (Queen of the West, Monarch, Switzerland, Lancaster, and Lioness). When the vessels came within range, the Union ironclads turned to face the enemy and the rams charged past them. The Confederate rams formed into two lines, each of four ships, and steamed to meet them. The CSS M. Jeff Thompson fired the first shot, and soon every ship was firing. The Colonel Lovell

and the General Beauregard headed toward Ellet's flagship, the Queen of the West, but at the last minute the Confederate rams reversed their paddles to slow themselves down, which made them turn. Ellet smashed into the side of the Lovell , toppling the Confederate vessel's smokestacks and leaving her filling with water. She drifted off to the eastern shore and sank, taking most of her crew with her. The Beauregard duly rammed the Queen of the West on her port wheelhouse, and the Union vessel limped away. Ellet was mortally wounded by a sharpshooter during the clash, and he died shortly afterwards. The Beauregard had virtually stopped in the water by this time, and the Monarch

headed straight for her. The General Sumter steered for the Monarch, but the Union ram slipped past the two Confederate vessels, and the Sumter and Beauregard collided. Helpless, the Beauregard

was fired on by the ironclad Benton , and her boiler was hit. The Confederate ram exploded, as did the M. Jeff Thompson. The remaining Confederate rams turned and fled, but one by one they were disabled and destroyed by the ironclads. Only the Earl Van Dorn escaped to the safety of Vicksburg.

This last great ram battle on the Mississippi River not only demonstrated the vulnerability of wooden gunboats to the fire of heavy shell guns, but it virtually destroyed the last remaining Confederate naval units on the river. Although the Confederate Navy would have other successes on the rivers, its gunboat fleet had been decimated. Ramming tactics were effective, but the action also demonstrated the need to combine the ram with a powerful armament. Union leaders took this lesson to heart, and upgraded the armament of their wooden fleet.

An extract from Essential Histories 5: The American Civil War (3) The war in the East 1863 -1865

The battle of Cold Harbor

Grant steered his army southeast once more, from the North Anna river toward Totopotomoy Creek, ever closer to Richmond. Lee's customary interposition kept nudging the Federals eastward even as they pressed south. Steady but desultory fighting at Totopotomoy led Grant toward scenes familiar from the earlier campaigns around Richmond.

By 2 June the armies were concentrating around Cold Harbor, where Lee's first great victory had been won on 27 June 1862 in the Battle of Gaines' Mill. The Confederate line that was hurriedly entrenched at the beginning of June 1864 ran right through the old battlefield; some of the 1864 fighting of greatest intensity would rage where the same armies had jousted two years before.

A Northern newspaperman described the Southern entrenchments as 'intricate, zig-zagged lines within lines, lines protecting flanks of lines … a maze and labyrinth of works within works and works without works.'

On 3 June, weary of being blocked at every turn and always inclined toward brutally direct action, Grant simply sent forward tens of thousands of men right into that formidable warren of defenses, and into the muzzles of rifles wielded by toughened veterans. The young Northerners obliged to participate in this disaster at Cold Harbor knew what the result would be. A member of General Grant's staff noticed them pinning to their uniforms pieces of paper bearing their names and home places, so that their bodies would not go unidentified. In very short order on that late-spring morning, 7,000 Union soldiers fell to Confederate musketry without any hope of success.

A Federal from New Hampshire wrote bluntly: 'It was undoubtedly the greatest and most inexcusable slaughter of the whole war … It seemed more like a volcanic blast than a battle … The men went down in rows, just as they marched in the ranks, and so many at a time that those in rear of them thought they were lying down.' General Emory Upton, who had been so successful at Rappahannock Station and Spotsylvania with carefully planned attacks, wrote on 4 June that he was 'disgusted' with the generalship displayed. 'Our men have … been foolishly and wantonly sacrificed,' he wrote bitterly; 'thousands of lives might have been spared by the exercise of a little skill.'

Some Southerners dealing out death from behind their entrenchments around Cold Harbor blanched at the carnage, but a boy from Alabama reflected on what was being inflicted upon his country and admitted that 'an indescribable feeling of pleasure courses through my veins upon surveying these heaps of the slain.' A pronouncement by that Alabamian's brigade commander, General Evander M. Law, has been the most often-cited summary of Cold Harbor. 'It was not war,' Law mused, 'it was murder.'

The bloodshed northeast of Richmond settled into steady, but deadly, trench warfare for the week after 3 June. Rotting corpses from the hopeless assault spread a suffocating stench across both lines; flies and other insects bedeviled the front-line troops; sniping between the lines inflicted steady casualties and made life difficult. Troops who had been scornful of digging earthworks earlier in the war now entrenched eagerly. Soon they had constructed elaborate lines and forts that stretched for miles across the countryside.

Much of the 10 months of war that remained to be fought in Virginia would feature such horrors, but the site of most of those operations would be south of the James river. On 12 June, Grant began carefully to extract substantial components of his army from the trenches and move them southward toward a crossing of the river. In managing that successful maneuver, Grant skilfully and thoroughly stole a march on General Lee, and achieved his most dramatic large-scale coup of 1864.

Soldiers would continue to battle in the outskirts of Richmond for the rest of the war, but the focus of operations henceforth would move below the James to the environs of Petersburg.

The Federal victory at Memphis deprived the Confederacy of a valuable bastion in their defence of the South and won for the Union naval dominance on the Mississippi, a crucial strategic artery. Cold Harbor was a bloody defeat for the Union. Ulysses Grant launched the Army of the Potomac in a bludgeoning frontal attack on Robert E. Lee's well-entrenched Army of Northern Virginia, and suffered terrible casualties. But Lee could not exploit this defensive victory and trench warfare set in with the Union noose gradually tightening over the next ten months around Richmond, the Confederate capital, which was only eight miles from Cold Harbor.

Further Reading

New Vanguard 49: Mississippi River Gunboats of the American Civil War 1861-65 (extract below) and New Vanguard 56: Union River Ironclad 1861-65 describe the design, development and operation of the innovative and improvised warships that contested the rivers and coastal waters of North America. The two battles are placed fully in context in Essential Histories 10: The American Civil War (2) The war in the West 1861-July 1863 and Essential Histories 5: The American Civil War (3) The war in the East 1863 -1865 (extract below). Essential Histories Specials 1: The American Civil War: This mighty scourge of war , which combines the present four American Civil War Essential Histories in a single volume, is published this month.

Further Reading

New Vanguard 49: Mississippi River Gunboats of the American Civil War 1861-65 (extract below) and New Vanguard 56: Union River Ironclad 1861-65 describe the design, development and operation of the innovative and improvised warships that contested the rivers and coastal waters of North America. The two battles are placed fully in context in Essential Histories 10: The American Civil War (2) The war in the West 1861-July 1863 and Essential Histories 5: The American Civil War (3) The war in the East 1863 -1865 (extract below). Essential Histories Specials 1: The American Civil War: This mighty scourge of war , which combines the present four American Civil War Essential Histories in a single volume, is published this month.

Kurtka mundurowa podporucznika marynarki Unii Kepi artylerzysty US „Navy” z czasów wojny secesyjnej Torba marynarza floty konfederackiej z czasów wojny secesyjnej Konfederacki kordelas marynarski, lata 60. XIX w. Oficerowie USS „Monitor”, lipiec 1862 r. Okręty pancerne Unii ostrzeliwują baterię konfederatów w Charleston, kwiecień 1863 r. Okręty pancerne Unii ostrzeliwują pozycje konfederatów nad rzeką Missisipi, 1862 r. Powder monkey – chłopiec okrętowy na pokładzie okrętu Unii Okręt pancerny USS „Onondaga” w zatoce na rzece James, 1862 r.

An extract from New Vanguard 49: Mississippi River Gunboats of the American Civil War 1861-65

The battle of Memphis

On May 10, 1862, the Union river fleet was above Fort Pillow, providing cover for mortar boats which were bombarding the Confederate positions. The vessel on point guard furthest downstream was the casemate ironclad USS Cincinnati. Smoke was spotted, and as the ironclad raised steam, Captain James E. Montgomery's River Defense Fleet rounded the bend. Montgomery commanded his full flotilla of eight rams, and led the way in his flagship, CSS Little Rebel. His vessels were making approximately nine knots, steaming against a one-knot current. The Confederates had the advantage of surprise, and before the Cincinnati could get fully under way the CSS General Bragg rammed her on her starboard side. The Cincinnati replied with a broadside at point-blank range, sending the large wooden ram reeling downstream. Just then the CSS General Sterling Price

smashed into the ironclad's stern, disabling her rudder.

By this time other ironclads had entered the fight, and the USS Carondolet

and the USS Mound City poured fire into the General Bragg, which drifted away, out of the fight. The CSS General Sumter was the next vessel to smash into the Cincinnati , causing severe damage. The leading mortar boat fired mortar shells over the Sumter to prevent sharpshooters on her decks firing into the ironclad. The CSS General Van Dorn replied by firing two 32-pounder shells into the mortar boat, disabling it completely. The ram then steamed past and rammed the Mound City, just seconds after the ironclad was rammed by the Sumter. The ironclad limped off, and sank in shallow water. Next, the ironclad USS Benton arrived and fired on the CSS Colonel Lovell, while the Carondolet

hit the Sumter's boiler, which exploded, causing heavy casualties.

Faced with annihilation, Montgomery withdrew the remainder of his force. As he now faced the entire Union river ironclad fleet, he had little option. As the Benton and Carondolet

gave chase, the Cincinnati sank in 11 feet of water, the last casualty of the battle. In an engagement that had only lasted about 40 minutes, two Union ironclads had been sunk for the loss of 108 men, and in return for heavy damage to three Confederate rams. Once more the effectiveness of ramming tactics had been demonstrated, this time against an armored opponent. Although what became known as the Battle of Plum Point was a Confederate victory, Montgomery could ill afford such losses, and both Union ironclads were raised and repaired. Next time the two fleets met, the North would have rams of their own.

On June 6, 1862, the two fleets met again off Memphis in a dawn battle, watched by numerous onlookers on the shore. Once again, the Confederates fielded eight vessels, as the extensive damage to the ram fleet had been repaired. Five Union ironclads came downriver stern first, followed by five wooden Ellet rams (Queen of the West, Monarch, Switzerland, Lancaster, and Lioness). When the vessels came within range, the Union ironclads turned to face the enemy and the rams charged past them. The Confederate rams formed into two lines, each of four ships, and steamed to meet them. The CSS M. Jeff Thompson fired the first shot, and soon every ship was firing. The Colonel Lovell

and the General Beauregard headed toward Ellet's flagship, the Queen of the West, but at the last minute the Confederate rams reversed their paddles to slow themselves down, which made them turn. Ellet smashed into the side of the Lovell , toppling the Confederate vessel's smokestacks and leaving her filling with water. She drifted off to the eastern shore and sank, taking most of her crew with her. The Beauregard duly rammed the Queen of the West on her port wheelhouse, and the Union vessel limped away. Ellet was mortally wounded by a sharpshooter during the clash, and he died shortly afterwards. The Beauregard had virtually stopped in the water by this time, and the Monarch

headed straight for her. The General Sumter steered for the Monarch, but the Union ram slipped past the two Confederate vessels, and the Sumter and Beauregard collided. Helpless, the Beauregard

was fired on by the ironclad Benton , and her boiler was hit. The Confederate ram exploded, as did the M. Jeff Thompson. The remaining Confederate rams turned and fled, but one by one they were disabled and destroyed by the ironclads. Only the Earl Van Dorn escaped to the safety of Vicksburg.

This last great ram battle on the Mississippi River not only demonstrated the vulnerability of wooden gunboats to the fire of heavy shell guns, but it virtually destroyed the last remaining Confederate naval units on the river. Although the Confederate Navy would have other successes on the rivers, its gunboat fleet had been decimated. Ramming tactics were effective, but the action also demonstrated the need to combine the ram with a powerful armament. Union leaders took this lesson to heart, and upgraded the armament of their wooden fleet.

An extract from Essential Histories 5: The American Civil War (3) The war in the East 1863 -1865

The battle of Cold Harbor

Grant steered his army southeast once more, from the North Anna river toward Totopotomoy Creek, ever closer to Richmond. Lee's customary interposition kept nudging the Federals eastward even as they pressed south. Steady but desultory fighting at Totopotomoy led Grant toward scenes familiar from the earlier campaigns around Richmond.

By 2 June the armies were concentrating around Cold Harbor, where Lee's first great victory had been won on 27 June 1862 in the Battle of Gaines' Mill. The Confederate line that was hurriedly entrenched at the beginning of June 1864 ran right through the old battlefield; some of the 1864 fighting of greatest intensity would rage where the same armies had jousted two years before.

A Northern newspaperman described the Southern entrenchments as 'intricate, zig-zagged lines within lines, lines protecting flanks of lines … a maze and labyrinth of works within works and works without works.'

On 3 June, weary of being blocked at every turn and always inclined toward brutally direct action, Grant simply sent forward tens of thousands of men right into that formidable warren of defenses, and into the muzzles of rifles wielded by toughened veterans. The young Northerners obliged to participate in this disaster at Cold Harbor knew what the result would be. A member of General Grant's staff noticed them pinning to their uniforms pieces of paper bearing their names and home places, so that their bodies would not go unidentified. In very short order on that late-spring morning, 7,000 Union soldiers fell to Confederate musketry without any hope of success.

A Federal from New Hampshire wrote bluntly: 'It was undoubtedly the greatest and most inexcusable slaughter of the whole war … It seemed more like a volcanic blast than a battle … The men went down in rows, just as they marched in the ranks, and so many at a time that those in rear of them thought they were lying down.' General Emory Upton, who had been so successful at Rappahannock Station and Spotsylvania with carefully planned attacks, wrote on 4 June that he was 'disgusted' with the generalship displayed. 'Our men have … been foolishly and wantonly sacrificed,' he wrote bitterly; 'thousands of lives might have been spared by the exercise of a little skill.'

Some Southerners dealing out death from behind their entrenchments around Cold Harbor blanched at the carnage, but a boy from Alabama reflected on what was being inflicted upon his country and admitted that 'an indescribable feeling of pleasure courses through my veins upon surveying these heaps of the slain.' A pronouncement by that Alabamian's brigade commander, General Evander M. Law, has been the most often-cited summary of Cold Harbor. 'It was not war,' Law mused, 'it was murder.'

The bloodshed northeast of Richmond settled into steady, but deadly, trench warfare for the week after 3 June. Rotting corpses from the hopeless assault spread a suffocating stench across both lines; flies and other insects bedeviled the front-line troops; sniping between the lines inflicted steady casualties and made life difficult. Troops who had been scornful of digging earthworks earlier in the war now entrenched eagerly. Soon they had constructed elaborate lines and forts that stretched for miles across the countryside.

Much of the 10 months of war that remained to be fought in Virginia would feature such horrors, but the site of most of those operations would be south of the James river. On 12 June, Grant began carefully to extract substantial components of his army from the trenches and move them southward toward a crossing of the river. In managing that successful maneuver, Grant skilfully and thoroughly stole a march on General Lee, and achieved his most dramatic large-scale coup of 1864.

Soldiers would continue to battle in the outskirts of Richmond for the rest of the war, but the focus of operations henceforth would move below the James to the environs of Petersburg.

No comments:

Post a Comment