https://ospreypublishing.com/thisweekhistory/

The events of the Franco-Prussian War fell into three main phases. Beginning in July 1870, it opened with a short campaign lasting until September, in which the major battles took place, after which it was largely considered to be over. The war continued until January 1871 because both sides could not agree peace terms. Finally, with peace declared and the war officially over, there was an attempted revolution and civil war in Paris known as the Commune. This was suppressed by the French in May, just as the Treaty of Frankfurt formally ending the war came into force.

Further reading

Essential Histories 51: The Franco-Prussian War 1870-1871 (extract below) places the hostilities and the warring nations in their historical context and describes the great battles, the sieges of Metz and Paris, and the establishment and obliteration of the Paris Commune. It also includes portraits of a soldier and a civilian caught up in the conflict and reviews its immediate and subsequent impact on politics and society. Men-at-Arms 233: French Army 1870-71 Franco-Prussian War (1) (extract below) and Men-at-Arms 237: French Army 1870-71 Franco-Prussian War (2) are studies of the uniforms, equipment and organisation of the losing side, and also document the inadequate reforms that were put in place to counter the Prussian threat. Volumes on the Prussian army will be published in 2004. Campaign 21: Gravelotte-St-Privat 1870 (extract below) is a detailed account of the bloody turning point in the invasion of France. With better generalship and organisation, their strong defensive positions and the superior firepower of their Chassepot rifles, the French could have won this battle. But when the Prussians finally abandoned frontal infantry attacks and fully exploited the superiority of their Krupp artillery, this ceased to be a possibility. German casualties of more than 20,000, twice the number sustained by the French, and the manner in which they were sustained were a foretaste of the butchery of the First World War, that far greater conflict easily traced back to the events of 1870-1871.

An Extract from Essential Histories 51: The Franco-Prussian War 1870-1871

The Context of the War

An Extract from Men-at-Arms 233: French Army 1870-71 Franco-Prussian War (1)

Command in the French Army of the Franco-Prussian War

An Extract from Campaign 21: Gravelotte-St-Privat 1870

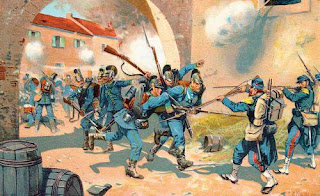

Action in the Mance ravine at the Battle of Gravelotte-St Privat

The events of the Franco-Prussian War fell into three main phases. Beginning in July 1870, it opened with a short campaign lasting until September, in which the major battles took place, after which it was largely considered to be over. The war continued until January 1871 because both sides could not agree peace terms. Finally, with peace declared and the war officially over, there was an attempted revolution and civil war in Paris known as the Commune. This was suppressed by the French in May, just as the Treaty of Frankfurt formally ending the war came into force.

Further reading

Essential Histories 51: The Franco-Prussian War 1870-1871 (extract below) places the hostilities and the warring nations in their historical context and describes the great battles, the sieges of Metz and Paris, and the establishment and obliteration of the Paris Commune. It also includes portraits of a soldier and a civilian caught up in the conflict and reviews its immediate and subsequent impact on politics and society. Men-at-Arms 233: French Army 1870-71 Franco-Prussian War (1) (extract below) and Men-at-Arms 237: French Army 1870-71 Franco-Prussian War (2) are studies of the uniforms, equipment and organisation of the losing side, and also document the inadequate reforms that were put in place to counter the Prussian threat. Volumes on the Prussian army will be published in 2004. Campaign 21: Gravelotte-St-Privat 1870 (extract below) is a detailed account of the bloody turning point in the invasion of France. With better generalship and organisation, their strong defensive positions and the superior firepower of their Chassepot rifles, the French could have won this battle. But when the Prussians finally abandoned frontal infantry attacks and fully exploited the superiority of their Krupp artillery, this ceased to be a possibility. German casualties of more than 20,000, twice the number sustained by the French, and the manner in which they were sustained were a foretaste of the butchery of the First World War, that far greater conflict easily traced back to the events of 1870-1871.

An Extract from Essential Histories 51: The Franco-Prussian War 1870-1871

The Context of the War

The Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71 was the largest and most important war fought in Europe between the age of Napoleon and the First World War. Since it ended in the establishment of a new German Empire, contemporaries often called it the ‘Franco-German War’, although neither name fits it perfectly. In 1870–71, ‘Prussian’ forces included those from an alliance of other German states, but Prussia and its interests dominated, just as in the Second World War German armies often included forces from other Axis members. The creation and continued existence of this new united Germany set the agenda for European international politics and war for the next century. The war also marked the end of the French Second Empire under Napoleon III, and with it the end of France’s dominant position in Europe. This was something that was never recovered, although in the longer term the war also established France as the most important and enduring republic on the continent. In a wider sense, both sides were conscious of a rivalry for dominance in western Europe between the French and German peoples that went back for centuries, chiefly for control of the lands that lie on either side of the Rhine and its tributaries from the North Sea to the Alps.

Despite its apparently ancient origins, the Franco-Prussian War also marked the beginning of the creation of modern Europe in every sense. It featured a mixture of aristocratic and conservative behaviour based on old ideas of personal rule and the Concert of Europe, together with the new realities of power politics and national bureaucracies. It was the first experience of what the Prussians called Millionenkrieg, ‘the war of the millions’, but both sides argued the formalities of international law, and treated the frontiers of neutral countries as if the laws that protected them were unbreakable barriers. Both King Wilhelm I of Prussia and Emperor Napoleon III of France made critical distinctions between their behaviour in the private sphere and as public heads of state. In its conduct also, the war mixed the weapons, tactics and methods of an earlier era with new military science and new political attitudes. Personalities decided this war, but so did armaments factories, public opinion, military staffwork and mass revolution.

An Extract from Men-at-Arms 233: French Army 1870-71 Franco-Prussian War (1)

Command in the French Army of the Franco-Prussian War

Some blamed the ‘Algerian experience’ for France’s defeat, claiming that her generals had forgotten how to fight a European war after 40 years of pursuing the wily tribesmen of North Africa. This is hardly true. Three-quarters of the generals active in 1870 had seen action in either the Crimea or in Italy, and over a third had served in both campaigns, including MacMahon, Bazaine and Canrobert. It is certainly true that many of the lessons learned there were less than fully relevant by 1870: unlike their German opponents the French had no experience of a war fought with breech-loading weapons, although they were aware of the theoretical changes in tactics that they had wrought. Nevertheless, they were well accustomed to commanding large bodies of men in the field, and to the difficulties inherent in moving and supplying them.

Where the French commanders were deficient was in the area of training and outlook. The lack of a comprehensive training programme for high-ranking officers tended to throw them back on their own experience. Not unnaturally this led them to believe that the methods employed so successfully in earlier campaigns were perfectly adequate and in no need of profound revision. The pervading anti-intellectual bias in the army – exemplified, in French minds at least, by contempt for what they saw as bespectacled Prussian ‘book’ generals – led to a degree of smugness which inhibited innovation and critical appraisal.

The Emperor himself was sufficiently concerned about practical training to create a huge camp at Châlons for the purpose of holding regular large-scale manoeuvres. In the event it proved to be of little use to the generals, although it was certainly valuable for regimental officers. The manoeuvres themselves were usually scripted in advance (the side representing the French invariably emerging the winner), which required little in the way of planning or initiative from the commanders involved – one year the battle of Austerlitz was re-enacted! On another occasion a group of visiting Prussian observers noted that similar exercises were ‘a superb military spectacle that had nothing to do with war’. The idea was that each year two sets of two to three divisions would train for two months at a time. Unfortunately only some 30 generals a year could make use of the facilities – scarcely one-eighth of the total.

The shortcomings of their practical education might have been ameliorated had they been willing to subject themselves to a course of theoretical study. This was particularly true at a time when technological developments were revolutionising strategy and tactics. Despite the plethora of material available, both from past masters and contemporary writers, there is little evidence that a lively intellectual debate flourished among the higher echelons of the army. That is not to say that there were no perceptive and thoughtful soldiers around. The able Gen. Trochu published a work entitled l’Armée Française en 1867, which highlighted many of the weaknesses inherent in the French military structure. The book was a best-seller, but earned its author considerable criticism and Imperial displeasure.

Another important factor was the constant interference of the Emperor. His assumption of supreme command relegated them to the status of supporting actors whose will to command (such as it was) ebbed away whilst he held centre stage. This often had dire consequences both on strategic decision-making and on battlefield tactics. Time and again the Germans presented the French with the opportunity for victory, only to be spared the consequences of their folly by their unenterprising opponents, who held back their all too eager men for lack of a formal order. The contrast with the adventurous (though not always intelligent) assertiveness of often quite junior German generals is stark. Excessive centralisation and a tradition of absolute obedience to superiors must also bear some of the responsibility for the lack of initiative shown by many French generals. One brigade commander at Gravelotte, who witnessed the rout of the Prussians in the Mance ravine, declined to exploit the situation, noting: ‘I did not think I should pursue them having been ordered to remain on the defensive.’ Earlier in the campaign Gen. Bonnemains was instructed to move his division; instead of immediately complying he asked headquarters whether this included his artillery and provost, which were not specifically mentioned in the order…

A further excuse often seized upon by post-war critics was the age of many senior commanders. While the average age was certainly higher than it had been in the Crimea or in Italy, it was still lower than that of their German opposite numbers. Corps commanders in l’Armée du Rhin for example, averaged some 59 years of age, two years younger than their German equivalents; whilst Moltke was 70 and Steinmetz, commander of 1st Army, was 73. In reality the issue was one of health rather than age: prolonged service in unhealthy climates had taken its toll of the young sabreurs of earlier days. Many were incapable of prolonged physical effort, including the Emperor, who suffered agonies during the campaign. Such a situation could hardly be expected to facilitate cool, reasoned thought and decisive actions.

Valid though these observations may be, they should not be overstated. Most commanders, even those in doubtful health, led from the front and suffered a high proportion of casualties: between 4 August and 2 September 16 generals were killed and a further 45 wounded. The problem was rather one of attitude. Against an opponent as aggressive and enterprising as the Germans, and under the unaccustomed gloom of early defeats, many felt themselves to be out of their depth. Gen. Bourbaki, the youngest of the French corps commanders, complained on the night of Mars-la-Tour: ‘We are too old for a war like this.’ It is scarcely surprising that they were defeated.

An Extract from Campaign 21: Gravelotte-St-Privat 1870

Action in the Mance ravine at the Battle of Gravelotte-St Privat

At just before 2.30pm Steinmetz ordered VIII Corps forward across the ravine. While Goeben’s assault with elements of 15th Division had been bloodily halted, for Steinmetz it had simply fuelled his belief in this course of action. The objective of VIII Corps’ assault was the farm of St-Hubert which would provide a foothold on the Rozérieulles plateau. It would also provide cover from Chassepot fire so that his artillery could move up to the edge of the ravine. Of Goeben’s Corps, the whole of 15th Division and 31 Brigade of 16th Division moved forward frontally to assault the farm.

The farm buildings sat just below the top of the ridge and commanded the steep eastern slope of the ravine. Above and to each side of the farm were the main trench lines of II and III Corps and the farm would have to be taken before any assault on these could be contemplated. The farm itself was held by a single battalion of the 80th Regiment of Aymard’s Division.

The three German brigades moved forward across the bottom of the ravine, 15th Division passing to either side of the causeway carrying the Gravelotte to St-Hubert road across the ravine, with 31 Brigade in support. As they crossed the stream a hail of bullets and shells smashed into their ranks. As they moved up the lower slopes, the thick undergrowth, trees and quarries broke up the company columns of 29 and 30 Brigades. Despite this, they managed to move up the slope to occupy the gravel-pits directly below the heights of the Point du Jour and St-Hubert, with 31 Brigade moving in behind. But from here they could move no further as the rifles and guns of Frossard’s Corps swept the area and their shattered ranks sought what cover they could in the pits and trees.

In this exposed and tenuous position, a localized French counter-attack would have swept all three brigades away, yet neither Frossard nor Leboeuf stirred. Instead, all their guns’ attention being drawn to the eastern slope, Steinmetz was able to bring forward his 150 guns from around Gravelotte to the western edge of the ravine by 3pm. Within a few minutes the farm of St-Hubert was a blazing ruin and the garrison was slaughtered. By 3.30 the survivors of the 80th had to retire to the main trench line just above the farm, and elements of three German units, 8th Jäger and 60th and 67th Infantry Regiments dashed forward to seize the ruins. The guns then began pounding the trenches and guns of Frossard’s Corps thereby discouraging any thought of a counter-attack to retake the German toe-hold in the ruined farm.

No comments:

Post a Comment