https://ospreypublishing.com/thisweekhistory/

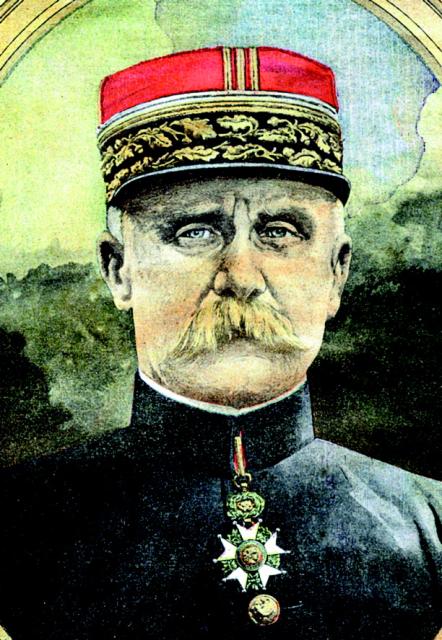

Philippe Pétain (1856 – 1951) Żołnierze francuscy w okopach pod Verdun

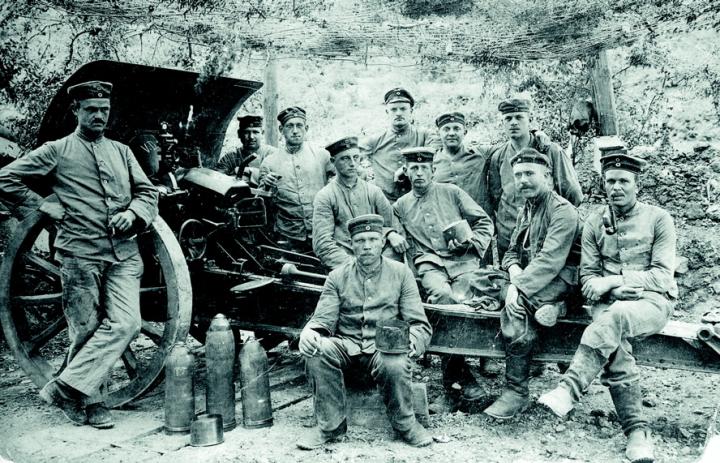

Niemiecka piechota przed natarciem luty 1916 r.

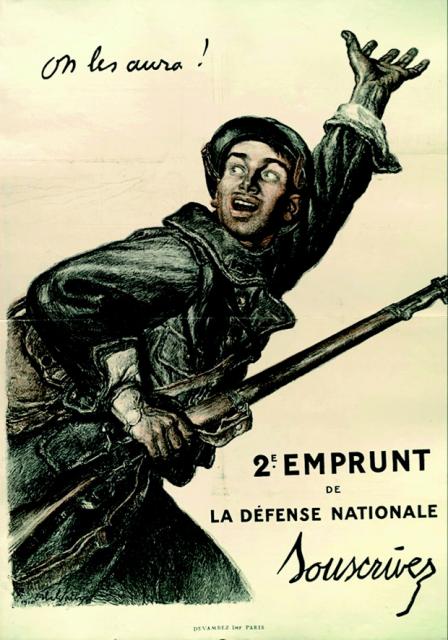

Francuski plakat reklamujący 2. pożyczkę obrony narodowej z hasłem Pétaina „Dorwiemy ich!”

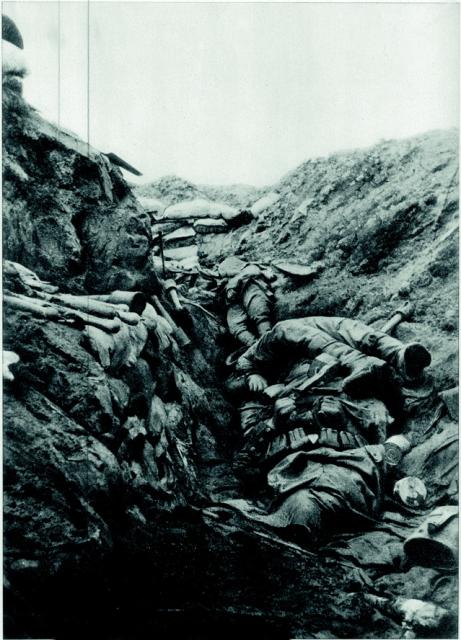

Ciała poległych w okopie pod Verdun

Niemiec przy ckm maxim MG 08 Atak piechoty francuskiej Niemiecki oddział szturmowy Niemieccy artylerzyści Francuska piechota odpoczywa w drodze na front Niemiecki żołnierz batalionu szturmowego rzucający wiązką granatów ręcznych, uzbrojony w karabin Mauser wz. 1898, na głowie Stahlhelm wz. 1916

On 26 February General Joffre, the French commander-in-chief, having quashed all suggestions of further retreat (the position was tactically as well as symbolically precious), put the defence of Verdun into the hands of General Henri Pétain, commander of the Second Army. Pétain is credited with the saying, 'Ils ne passeront pas' (They shall not pass) and was true to it. Months of barrage, attack and counterattack followed and the battle did not end until mid-December when the frontline was almost completely restored to where it had been on the day of Falkenhayn's opening assault. Casualties totalled more than 700,000 with only slightly more French than German. The bloody attrition planned by Falkenhayn had turned out to be mutual.

Further reading

Campaign 93: Verdun 1916 (extract below) is a full account of the ten months of fighting that turned the green agricultural landscape into 'a broad, brown band ... [a] sinister brown belt, a strip of murdered Nature'. Essential Histories 14: The First World War (2) The Western Front 1914-1916 (extract below) provides an overview and places this terrible battle in the larger context of the first half of the First World War in its western theatre. The opposing armies are portrayed in Men-at-Arms 286: The French Army 1914-18, Men-at-Arms 80: The German Army 1914-18 and Warrior 12: German Stormtrooper 1914-18. Elite 78: World War I Trench Warfare (1) 1914-16 presents the action as the culmination of 18 months evolution of tactics and combat techniques.

An Extract from Essential Histories 14: The First World War (2) The Western Front 1914-1916

Attack at Verdun

An American volunteer pilot described what he saw from the air that summer:

An Extract from Campaign 93: Verdun 1916

The Chasseurs' stand and Colonel Driant's death

Verdun 1916 (21 February)

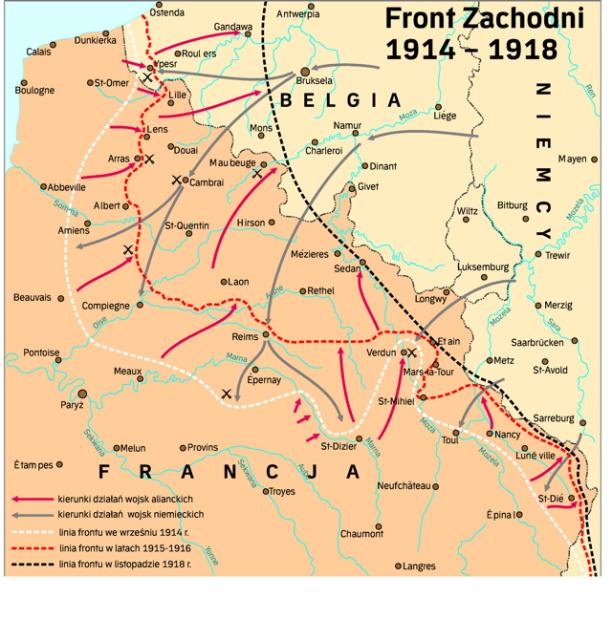

At the end of 1915 both the Germans and the Allies were developing plans, for the following year, to break the deadlock that gripped them. The Allies' strategy was three-pronged: the French and British were to mount a summer offensive across the Somme whilst other forces put new pressure on the Central Powers on the Italian and Eastern Fronts. The Germans decided on a strategy of attrition directed specifically at France. General Erich von Falkenhayn, Chief of the German General Staff, who believed this was their best if not only option, reasoned, 'If we succeed in opening the eyes of their people to the fact that in a military sense they have nothing more to hope for ... England's best sword would be knocked out of her hand. To achieve this object the uncertain method of a mass breakthrough, in any case beyond our means, is unnecessary. We can probably do enough for our purposes with limited resources. Within our reach behind the French sector of the Western Front there are objectives for the retention of which the French General Staff would be compelled to throw in every man they have. If they do so the forces of France will bleed to death - as there can be no question of voluntary withdrawal - whether we reach our objective or not.'

Falkenhayn chose Verdun as his killing ground and Germany struck first. Verdun was a historic keystone in France's frontier defences against Germany. Dating from Roman times, it had changed hands on several occasions, falling to the Germans the last time in the Franco-Prussian War. When the attack began on 21 February 1916, the French were not well prepared but they were better prepared than they would have been had severe winter weather not caused the attack to be postponed from its original date of 12 February. Even so, after the first four days of fighting the French situation would have been desperate, but for some heroic resistance at key points, and the Germans' lack of reserves and over-cautious exploitation of their early gains.

Erich von Falkenhayn (1861 – 1922)Falkenhayn chose Verdun as his killing ground and Germany struck first. Verdun was a historic keystone in France's frontier defences against Germany. Dating from Roman times, it had changed hands on several occasions, falling to the Germans the last time in the Franco-Prussian War. When the attack began on 21 February 1916, the French were not well prepared but they were better prepared than they would have been had severe winter weather not caused the attack to be postponed from its original date of 12 February. Even so, after the first four days of fighting the French situation would have been desperate, but for some heroic resistance at key points, and the Germans' lack of reserves and over-cautious exploitation of their early gains.

Philippe Pétain (1856 – 1951) Żołnierze francuscy w okopach pod Verdun

Niemiecka piechota przed natarciem luty 1916 r.

Francuski plakat reklamujący 2. pożyczkę obrony narodowej z hasłem Pétaina „Dorwiemy ich!”

Ciała poległych w okopie pod Verdun

Niemiec przy ckm maxim MG 08 Atak piechoty francuskiej Niemiecki oddział szturmowy Niemieccy artylerzyści Francuska piechota odpoczywa w drodze na front Niemiecki żołnierz batalionu szturmowego rzucający wiązką granatów ręcznych, uzbrojony w karabin Mauser wz. 1898, na głowie Stahlhelm wz. 1916

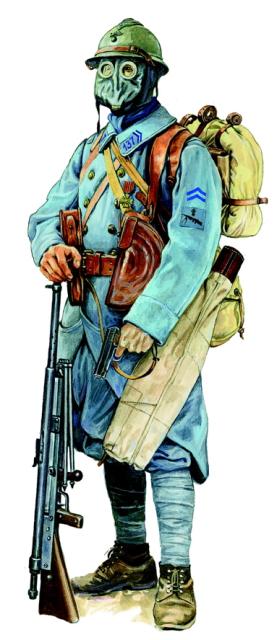

Francuski piechur w szynelu i hełmie Adrian wz. 1915 oraz masce przeciw-gazowej M2, uzbrojony w ręczny karabin maszynowy Chauchat wz. 1915 i pistolet PA Ruby

On 26 February General Joffre, the French commander-in-chief, having quashed all suggestions of further retreat (the position was tactically as well as symbolically precious), put the defence of Verdun into the hands of General Henri Pétain, commander of the Second Army. Pétain is credited with the saying, 'Ils ne passeront pas' (They shall not pass) and was true to it. Months of barrage, attack and counterattack followed and the battle did not end until mid-December when the frontline was almost completely restored to where it had been on the day of Falkenhayn's opening assault. Casualties totalled more than 700,000 with only slightly more French than German. The bloody attrition planned by Falkenhayn had turned out to be mutual.

Further reading

Campaign 93: Verdun 1916 (extract below) is a full account of the ten months of fighting that turned the green agricultural landscape into 'a broad, brown band ... [a] sinister brown belt, a strip of murdered Nature'. Essential Histories 14: The First World War (2) The Western Front 1914-1916 (extract below) provides an overview and places this terrible battle in the larger context of the first half of the First World War in its western theatre. The opposing armies are portrayed in Men-at-Arms 286: The French Army 1914-18, Men-at-Arms 80: The German Army 1914-18 and Warrior 12: German Stormtrooper 1914-18. Elite 78: World War I Trench Warfare (1) 1914-16 presents the action as the culmination of 18 months evolution of tactics and combat techniques.

An Extract from Essential Histories 14: The First World War (2) The Western Front 1914-1916

Attack at Verdun

Almost encircled by ridges and hills on both banks of the Meuse, Verdun was also protected by rings of forts. The strongest, in theory, was Fort Douaumont, perched on a 1,200-foot height north-east of the city, on the right bank. However, the strength of the forts was illusory, many of their guns having been removed to provide extra firepower for the French autumn operations. A member of the Chamber of Deputies, Emile Driant, had infuriated Joffre by disclosing Verdun's weaknesses to fellow Deputies. By a remarkable twist of fate, Driant, in February 1916, was commanding two battalions of Chasseurs in the Bois des Caures - a feature at the epicentre of the German attack.

The battle opened at dawn on 21 February. A single 38cm naval gun, 20 miles from the city, fired the first round at a bridge spanning the Meuse. This shell, which missed its target, was the prelude to a nine-hour bombardment of unprecedented savagery. More than 80,000 shells fell in the Bois des Caures alone. With their rearward communications severed, the bewildered defenders were in no condition to repel a major assault. Fortunately for the French, the German planners had been too cautious, limiting infantry operations on the first day to strong fighting patrols which would employ infiltration tactics to seek out weak spots in the French line. Only the VII Reserve Corps commander, von Zwehl, disregarded these orders and showed what might have been achieved. He deployed storm troops just behind the fighting patrols and, in five hours, secured the Bois d'Haumont. In the Bois des Caures, however, Driant's shrewd use of strongpoints instead of continuous trench lines enabled the surviving Chasseurs to defend that position obstinately against the German XVIII Corps.

On 22 February von Zwehl was again the pace-setter, bursting through a regiment of Territorials on the French 72nd Division's left at the Bois de Consenvoye and then seizing Haumont to tear open a gap in the French first line and expose the left flank of the Bois des Caures. During the late afternoon the heroic Driant was killed whilst endeavouring to withdraw his shattered battalions to Beaumont. Much of the French front line had crumbled but despite terrible casualties the defenders were inflicting increasing losses on the Germans, especially among their key storm troops. The next day the Germans came up against an intermediate line that had only recently been created on De Castelnau's orders and so was not marked on German maps. The dogged defence of Herbebois by the French 51st Division was overcome that evening but overall German gains were disappointing on 23 February. The 37th African Division began to reach the battlefield to shore up the depleted units of the French XXX Corps and, ominously for the Germans, powerful French artillery was massing on the left bank of the Meuse.

In the short term these developments were of scant comfort to the French. Before dawn on 24 February Samogneux was in German hands. The French 51st and 72nd Divisions were close to collapse. Beaumont then fell and in barely three hours the French second position broke apart. Algerian Zouaves and Moroccan Tirailleurs of the 37th Division, committed piecemeal to the battle and with no protection from the bitter cold or the fury of the German guns, could not stabilise the situation. Indeed, the 3rd Zouaves - facing the Brandenburgers of the German III Corps - melted away, so uncovering Fort Douaumont, a pivotal point in the defences. As darkness descended, the leading elements of Balfourier's French XX Corps arrived to relieve the battered XXX Corps but there was no guarantee that these fresh troops could repair the disintegrating front.

On 25 February the 24th Brandenburg Regiment entered the gap left by the 3rd Zouaves. Some detachments pushed beyond the stipulated objectives as far as Fort Douaumont. Here, partly because of a French staff and command muddle, the garrison numbered less than 60. Emboldened by the curious inactivity of the fort, a few pioneers, under a sergeant named Kunze, pressed through the outer defences to the dry moat. Still undetected, they climbed through a gun embrasure in to one of the fort's galleries. Though German 42cm shells had not inflicted critical damage on the fort, the shock waves and fumes they produced had driven the defenders to shelter in the bowels of the fort. Kunze was followed in by three more small groups of Brandenburgers and the dejected garrison surrendered by 4.30 pm.

The capture of such a prize at minimal cost sparked national rejoicing in Germany. The attackers appeared to have a clear route into Verdun and the commander of the French Central Army Group, De Langle de Cary, had already advocated withdrawal to the heights to the east and south-east. However, the combative De Castelnau, at French General Headquarters, opposed this policy. Having ensured that Pétain's Second Army would be brought out of reserve to hold the left bank of the Meuse, he travelled to Verdun on 25 February and scotched all thoughts of retirement. He also called for Pétain's area of responsibility to embrace the right bank of the Meuse, which was to be defended at all costs. To some extent these measures were playing into Falkenhayn's hands, yet, as De Castelnau knew, French doctrine and national sentiment made it inconceivable to abandon Verdun.

Like Plumer at Ypres in 1915, the pragmatic Pétain's preference would probably have been controlled withdrawal. However, as an unambitious officer who shunned intrigue and ostentation, Pétain was ideally suited to the role in which he was now cast. Again like Plumer, he understood modern firepower and was trusted by his troops. His very presence at Verdun lifted morale and he inspired renewed confidence in the Verdun forts as the backbone of a 'Line of Resistance'. French artillery was concentrated to give the Germans a taste of attrition. Above all, Pétain grasped the importance of logistics. As rail links to Verdun were cut by German long-range artillery, he took pains to ensure that supplies were maintained along the single viable route south - a road which became known as the Voie Sacrée (Sacred Way). By June vehicles were moving up and down this lifeline at the rate of one every 14 seconds.

An American volunteer pilot described what he saw from the air that summer:

'Every sign of humanity has been swept away. The woods and roads have vanished like chalk wiped from a blackboard; of the villages nothing remains but gray smears where stone walls have tumbled together. The great forts of Douaumant and Vaux are outlined faintly, like the tracings of a finger in wet sand. Of the trenches only broken, half-obliterated links are visible.'

An Extract from Campaign 93: Verdun 1916

The Chasseurs' stand and Colonel Driant's death

The 56th and 59th battalions started that day with 1,300 officers and men. Caporal Maurice Brassard, one of the handful of survivors from the 56th, said that of every five riflemen, 'two are buried alive in their shattered dug-outs, two are wounded and the fifth waits'. Some 40 artillery batteries and 50 trench mortars fired an estimated 80,000 rounds at the wood - an area of only 1,300 x 800 metres. Trees were shredded and uprooted. Trenches and dug-outs collapsed. How many of the defenders survived this storm of steel will never be known, but when the bombardment ceased at 4.00pm, handfuls of riflemen emerged from their shelters to do battle. They were red-eyed, deafened and many were injured. Most machine guns were smashed, some men had only grenades and bayonets. The guns continued to pound the area behind the wood when, in the dying light of the afternoon, German flamethrower squads led small assault columns in among the shattered stumps of the Bois des Caures. The Chasseurs were attacked by elements of the 42nd Brigade of the German 21st Division, spearheaded by five pioneer detachments and flamethrower teams.

In places there was no resistance. In others, such as abris (bunker) 17, a machine gun stuttered to life and the Germans were pinned down. Sergent Léger and five Chasseurs kept the gun in action until they ran out of ammunition; Léger managed to exhaust his store of 40 hand-grenades too before he was wounded and passed out. Nearby, Sergent Legrand and six Chasseurs found they had only two working rifles with them, but they fought to the death. Only one, Caporal Hutin, was wounded and captured. (Sadly he was deported and executed in 1944 for his activities in the resistance.)

During the first days of the battle, even when hopelessly outnumbered, the French launched frequent counterattacks. Many collapsed in bloody ruin, shot to pieces on the start-line by German artillery, but others achieved results out of proportion to the number of men involved. The Germans found it difficult to retain control of their units in the tangled wreckage of the Bois des Caures. There seems to have been a certain complacency among others - at 8.00pm Lieutenant Robin led a spirited counterattack in the midst of a snow-shower and literally caught the Germans napping in strongpoint 'S7'.

By midnight the Chasseurs held a good part of their original positions, but there were precious few men left on their feet. Driant visited each post during the night. Robin asked what he was supposed to do with 80 men against a German brigade?

It takes nothing away from Driant and his Chasseurs to observe that the Germans pulled their punches on 21 February. The bulk of the German infantry remained in their stollen while the pioneers led company-sized assault groups into the French positions. The Germans did not follow the barrage with an immediate, all-out infantry assault.

Driant's luck ran out that afternoon. Strongpoints were overwhelmed one by one. Dwindling groups of survivors conducted a fighting retreat. Driant burned his papers before evacuating his command post. He split the survivors into three groups before stopping off at the regimental aid post, defended by Lieutenant Simon and Sergent-Major Savart, who held off a large number of Germans with deadly accurate rifle fire. But as they picked their way back through the shattered tree stumps, Driant paused to give a field dressing to Chasseur Papin. Pionnier Sergent Jules Hacquin leapt into a shell hole just ahead when he heard the colonel cry out, 'Oh Là! Mon Dieu.' Hacquin went back with another NCO but Driant was already dead, his eyes half-closed.

Like Leonidas, at the cost of his life and his command, Driant won time for his comrades to prepare an effective defence. Driant is deservedly a hero, yet it is worth noting that several other regiments resisted with the same dogged determination. The Germans made little progress the next day either.

No comments:

Post a Comment