Further reading

Essential Histories 39: The Napoleonic Wars (4) The fall of the French empire 1813-1815 (extract below) plays out the drama of the final three years of Napoleon’s empire with its two climaxes on the battlefields of Leipzig and Waterloo.

Warrior 22: Imperial Guardsman 1799-1815 and Warrior 57: French Napoleonic Infantryman 1803-15 respectively portray the elite infantry and the line footsoldiers who formed the backbone of Napoleon's armies.

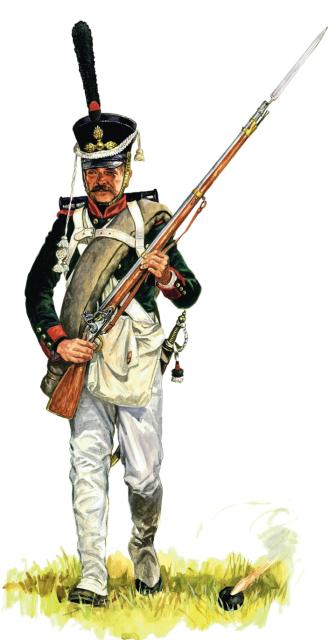

Men-at-Arms 381: Prussian Staff & Specialist Troops 1791-1815 and Warrior 62: Prussian Regular Infantryman 1808-15 (extract below) focus on Napoleon’s Prussian enemies, so comprehensively crushed by him in 1806 but very much a part of his nemesis in the final campaigns of the Napoleonic Wars from Leipzig to Waterloo.

An Extract from Essential Histories 39: The Napoleonic Wars (4) The fall of the French empire 1813-1815

Six Days of Glory

By 9 February Schwarzenberg had proceeded as far as Troyes, but the Allies failed to coordinate simultaneous movements up the Marne by Blücher, Yorck, and Kleist, all of whom struggled with impaired communications caused by melting snow and the onset of heavy rain. By spreading his force of 50,000 men too widely in an attempt to envelop the French around Sézanne, Blücher and his subordinates fell victim to a series of some of Napoleon's most impressive victories.

The first came at Champaubert on 10 February, where Napoleon's force of 30,000 overwhelmed 5,000 Russians under General Olssufiev whom Blücher had detached to operate in the area. On the following day the Emperor struck at Montmirail, defeating a Prussian corps under Sacken before Blücher could complete his attempts at regrouping his scattered forces. On 12 February the French were victorious again at Château-Thierry, though at the same time Macdonald was unable to prevent the Allies from forcing a passage of the Marne. On 14 February Blücher launched a counterattack at Vauchamps, but was repulsed. All told, what became known as the Six Days' Campaign cost the Allies 20,000 men. Nevertheless, although Napoleon's successes raised French morale, they failed to have a significant effect on the Allies, who brought up 30,000 Russians under Winzingerode to join Blücher's army at Châlons.

Meanwhile, to the south, Schwarzenberg was pushing west toward Guignes and Chalmes on the river Yerre, driving before him the combined army under Oudinot, Victor and Macdonald. By the middle of the month the Allies were within 20 miles (30 km) of Paris. Panic once again gripped the capital. Schwarzenberg, however, ordered a halt to assess the risks to his flanks. No sooner had he decided to withdraw than Napoleon pounced on and routed his advance guard at Valjouan on 17 February, and on the following day the Emperor defeated Schwarzenberg again at Montereau.

An Extract from Warrior 62: Prussian Regular Infantryman 1808-15

A Prussian’s First Experience of Battle

On 27 September 1812 Karl Renner, Musketier in the 1st Battalion of the 2. Westpreußisches Infanterie-Regiment, saw combat for the first time:

About a quarter of a mile south of Eckau our infantry formed up behind a small piece of rising ground. When this had been done, we put the muskets together and we were allowed to rest a while, as we had been marching all the night until then, shortly before noon. In front of our battalion, on the rising ground a battery had unlimbered. In order to watch the deployment of the enemy, many curious soldiers ran to the top of this rising ground, I among them. We had been looking for only a few minutes, when we saw in the distance some smoke rise up, and almost at the same moment a cannon ball passed above us with a loud buzzing. Our artillery, which had been waiting ready for action on this rising ground (which we immediately vacated), replied to the kind invitation of the enemy. The command 'Gewehr in die Hand!' [Take up arms!] was given … But the enemy cannon continued as before, starting to bring death and destruction among us, which caused fear and terror among the young soldiers, who tried to escape the imminent danger by ducking down. A soon as our brave battalion commander, Major von Löbell (now [in 1829] General-Major), saw this, he coolly rode up and down our front, as if on the parade ground. Several other officers showed the same calmness and fearlessness, especially our brave company commander, Kapitain von Rohr (now Oberst and commander of the 26. Infanterie-Regiment), and the adjutant of our battalion, Lieutenant von Legat (now Oberst in the Ministry of War). This display made us so proud that nobody thought any more of ducking, even though the buzzing of the balls became more and more intense.

We had stood there a few minutes, and the command was shouted 'Tirailleure vor!' [Skirmishers advance!] The bugler blew for the first section to deploy as skirmishers. In front of us there was a thicket of birch and alder trees, encircled by a shallow and dry ditch with a thin fence, which we used for cover. We had just arrived at this place, when the enemy bullets began whizzing above us in massed volleys, and here and there one of them punched through the tiny fence, oblivious to the fact that it was our sole protection. We couldn't not respond to the enemy, so we sent bullets back to them, but were not able to make out if a few of them achieved their aim. The enemy skirmishers who were hidden in the undergrowth were most discontent with our counter-greeting, they came out of the forest, shouting 'Hurrah!', and in a number so superior to ours that they forced us to leave our position. The retreat was performed with the greatest precision, and as only a few were wounded, the whole affair seemed to have been but an exercise on the parade ground. Now, in our first engagement, we had convinced ourselves that the banging and whizzing of bullets would not bear inevitable death, but that above us, in front of us, at our sides and behind us there was plenty of space to cause them to miss us.

No comments:

Post a Comment