https://ospreypublishing.com/thisweekhistory/

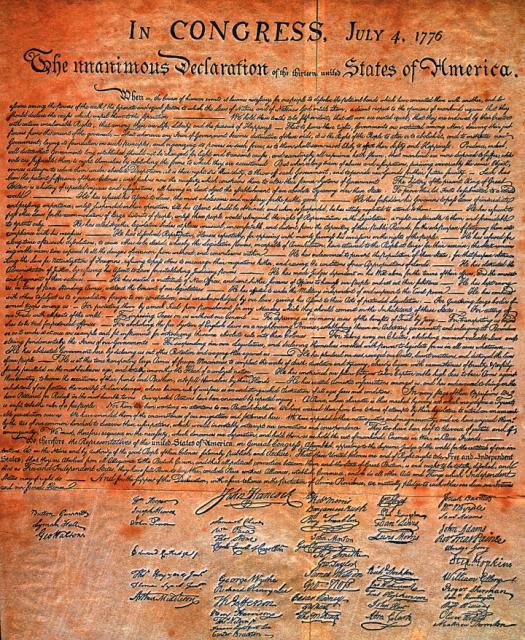

Podpisanie amerykańskiej Deklaracji niepodległości 4 lipca 1776 r.

Tzw. herbatka bostońska – bostończycy wyrzucają do wody transport herbaty w proteście przeciwko wysokim cłom, 16 grudnia 1773 r., litografia z 1846 r.

Jerzy Waszyngton, dowódca armii zbuntowanych kolonii, a potem pierwszy prezydent Stanów Zjednoczonych

Deklaracja niepodległości z podpisami 56 członków Kongresu

Okręty brytyjskie podczas walk o Boston w 1775 r.

Medal wybity z okazji wyzwolenia Bostonu w marcu 1776 r.

Jerzy Waszyngton przeprawia się przez rzekę Delaware, mal. Emanuel Leutze, 1851 r

Lord Howe ewakuuje wojska brytyjskie z Bostonu, marzec 1776 r.

Jerzy Waszyngton pod Yorktown, mal. James Peale

Unrest had been growing among the colonists for more than ten years, their resentment stirred up partly by the imposition of a series of taxes on the colonies and, more generally, by Britain’s imperial attitude toward North America. Protest organizations such as the ‘Sons of Liberty’ sprang up; taxed goods were boycotted; and serious riots ensued. In the ‘Boston Massacre’ of 1770, British regulars fired on a mob and killed five. Tension continued to mount; hostility was open and mutual. After the Boston Tea Party of December 1773, Parliament introduced a series of Acts (known locally as the Coercive or Intolerable Acts) in an attempt to restore order, especially in Boston and Massachusetts, the epicentre of opposition. Matters worsened, and the militias began to prepare themselves for armed resistance, illicitly equipping themselves with weapons, ammunition and other supplies from the public arsenals.

On 18 April a strong but inexperienced British force of grenadiers and light infantry was sent from Boston to retrieve a large cache of weapons and gunpowder reported to be stored in Concord, 16 miles to the northwest. The next morning, after a chaotic crossing of the Charles River and a night march, they were confronted by a 70-strong company of militia blocking the road to Concord on Lexington Common. The militia had been alerted by Paul Revere on his famous ride. (See below for an account of this accidental, minor skirmish that started one of history’s most significant wars.) The colonials resisted more strongly around Concord later in the morning, and the British column, having found and destroyed some materiel, made a fighting withdrawal to Boston.

After several weeks of indecisive leadership on both sides, the British won a bloody victory on Breed’s Hill, the battle called after Bunker’s Hill, the strategic high ground adjacent to it. Surprised by the colonists’ show of force, British Commander-in-Chief, General Gage, soon to be replaced, wrote, ‘the tryals we have shew that the Rebels are not the despicable Rabble too many have supposed them to be’. The war was to end formally eight years later with the United States of America victorious and independent.

Further reading

The events of 1775 in and around Boston are recounted in Campaign 37: Boston 1775 – The shot heard around the world (extracts below). Subsequent major battles and campaigns are covered by Campaign 67: Saratoga 1777 – Turning Point of a Revolution , Campaign 109: Guilford Courthouse 1781 – Lord Cornwallis's Ruinous Victory and Campaign 47: Yorktown 1781 – The World Turned Upside Down.

Men-at-Arms 273: General Washington's Army (1) 1775-78 , Men-at-Arms 290: General Washington's Army (2) 1779-83, Men-at-Arms 285: King George's Army 1740-93 (1) Infantry, Men-at-Arms 289: King George's Army 1740-93 (2) and Men-at-Arms 292: King George's Army 1740-1793 (3) are detailed examinations of the uniforms, equipment, weapons, tactics and organisation, and also the personalities of the opposing armies. For a more personal insight into the lives and experiences of the British soldier in this era see Warrior 19: British Redcoat 1740–93 and Warrior 42: Redcoat Officer. Essential Histories 45: The American Revolution 1774–1783 (extract below) places the events of this week in 1775 in the full context of the war, viewed from political, strategic, tactical and individual perspectives.

An extract from Campaign 37: Boston 1775 – The shot heard around the world

Lexington Common

An extract from Essential Histories 45: The American Revolution 1774–1783

The Build-up to War

Two Extracts from Campaign 37: Boston 1775 – The shot heard around the world

Two Questions

Podpisanie amerykańskiej Deklaracji niepodległości 4 lipca 1776 r.

Tzw. herbatka bostońska – bostończycy wyrzucają do wody transport herbaty w proteście przeciwko wysokim cłom, 16 grudnia 1773 r., litografia z 1846 r.

Jerzy Waszyngton, dowódca armii zbuntowanych kolonii, a potem pierwszy prezydent Stanów Zjednoczonych

Deklaracja niepodległości z podpisami 56 członków Kongresu

Medal wybity z okazji wyzwolenia Bostonu w marcu 1776 r.

Jerzy Waszyngton przeprawia się przez rzekę Delaware, mal. Emanuel Leutze, 1851 r

Jerzy Waszyngton pod Yorktown, mal. James Peale

Unrest had been growing among the colonists for more than ten years, their resentment stirred up partly by the imposition of a series of taxes on the colonies and, more generally, by Britain’s imperial attitude toward North America. Protest organizations such as the ‘Sons of Liberty’ sprang up; taxed goods were boycotted; and serious riots ensued. In the ‘Boston Massacre’ of 1770, British regulars fired on a mob and killed five. Tension continued to mount; hostility was open and mutual. After the Boston Tea Party of December 1773, Parliament introduced a series of Acts (known locally as the Coercive or Intolerable Acts) in an attempt to restore order, especially in Boston and Massachusetts, the epicentre of opposition. Matters worsened, and the militias began to prepare themselves for armed resistance, illicitly equipping themselves with weapons, ammunition and other supplies from the public arsenals.

On 18 April a strong but inexperienced British force of grenadiers and light infantry was sent from Boston to retrieve a large cache of weapons and gunpowder reported to be stored in Concord, 16 miles to the northwest. The next morning, after a chaotic crossing of the Charles River and a night march, they were confronted by a 70-strong company of militia blocking the road to Concord on Lexington Common. The militia had been alerted by Paul Revere on his famous ride. (See below for an account of this accidental, minor skirmish that started one of history’s most significant wars.) The colonials resisted more strongly around Concord later in the morning, and the British column, having found and destroyed some materiel, made a fighting withdrawal to Boston.

After several weeks of indecisive leadership on both sides, the British won a bloody victory on Breed’s Hill, the battle called after Bunker’s Hill, the strategic high ground adjacent to it. Surprised by the colonists’ show of force, British Commander-in-Chief, General Gage, soon to be replaced, wrote, ‘the tryals we have shew that the Rebels are not the despicable Rabble too many have supposed them to be’. The war was to end formally eight years later with the United States of America victorious and independent.

Further reading

The events of 1775 in and around Boston are recounted in Campaign 37: Boston 1775 – The shot heard around the world (extracts below). Subsequent major battles and campaigns are covered by Campaign 67: Saratoga 1777 – Turning Point of a Revolution , Campaign 109: Guilford Courthouse 1781 – Lord Cornwallis's Ruinous Victory and Campaign 47: Yorktown 1781 – The World Turned Upside Down.

Men-at-Arms 273: General Washington's Army (1) 1775-78 , Men-at-Arms 290: General Washington's Army (2) 1779-83, Men-at-Arms 285: King George's Army 1740-93 (1) Infantry, Men-at-Arms 289: King George's Army 1740-93 (2) and Men-at-Arms 292: King George's Army 1740-1793 (3) are detailed examinations of the uniforms, equipment, weapons, tactics and organisation, and also the personalities of the opposing armies. For a more personal insight into the lives and experiences of the British soldier in this era see Warrior 19: British Redcoat 1740–93 and Warrior 42: Redcoat Officer. Essential Histories 45: The American Revolution 1774–1783 (extract below) places the events of this week in 1775 in the full context of the war, viewed from political, strategic, tactical and individual perspectives.

An extract from Campaign 37: Boston 1775 – The shot heard around the world

Lexington Common

During the afternoon of 18 April, mounted British officers left to patrol the roads between Cambridge and Concord. Seeing one group, led by Major Mitchell (5th), pass through Menotomy, a Lexington ‘minuteman’, Sergeant William Munroe, organized a guard for the house in which Adams and Hancock were staying; but the patrol rode through Lexington and past Hartwell’s Tavern, before turning back, around 2030. By now, the only people ignorant of events were the regulars themselves.

At about 2200, the 700 men of Gage’s 21 flank companies were woken and led to the Common, where the boats were waiting. The lack of prop¬er planning was soon obvious: companies were late, their commander, Lieutenant Colonel Francis Smith (10th) was among the last to arrive, and only the intervention of the 23rd’s adjutant prevented total chaos. After crossing the Back Bay to Lechemere Point, the men waded ashore (the boats were too heavily laden to be beached) and waited three hours while ammunition and food was distributed, before finally setting off at 0200.

Revere, having arranged the signal in the Old North church, rode towards Cambridge, but a patrol forced him to detour and he reached Lexington at midnight. There, he was joined by William Dawes, who had ridden across Boston Neck and through Roxbury and Cambridge — together with Dr Samuel Prescott, a Concord physician, they set off to rouse the countryside. Revere was captured by Mitchell’s patrol (which had already intercepted three other riders) three miles beyond Lexington, but Dawes and Prescott both escaped and continued their mission. Alarmed by Revere’s claim that every militia company for 50 miles was alerted, Mitchell returned to Lexington, where he released Revere (who went to help Adams and Hancock escape), and headed off to meet Smith, who, by 0300, had just passed through Menotomy.

The senior militia officer at Lexington, Captain John Parker, had sent four scouts to locate the regulars; three were captured, but the fourth returned, reporting that Smith was only half a mile away. Parker formed his men — most of whom had been in Buckman’s Tavern since 0100, hav¬ing first assembled when Revere arrived in a two-deep line across the Bedford road (along which Adams and Hancock had earlier fled). As they lined up, they could see the British advance guard, under Major Thomas Pitcairn of the Marines, approaching the common.

Pitcairn’s two leading companies (4th and 10th) were expecting trouble after Mitchell’s pessimistic report. They swung to the right of the Meeting House and deployed into line, while Pitcairn rode to the left, ordering the militia to lay down their arms and leave. Parker, realising the odds, told his men to disperse, but to keep their arms, and as they did so, a single shot rang out, then a volley from the regulars. A dozen militia tried to return the fire, but the troops (mostly inexperienced and with months - even years - of Bostonian provocation behind them) became uncontrollable. Ignoring their officers, they charged with the bayonet and Smith, arriving with the main body, had to find a drummer to beat the recall. When order was restored, eight of Parker’s men lay dead, and ten more were wounded — British casualties were one sergeant and Pitcairn’s horse both slightly wounded. The time was a little after 0500. At about the same time, two companies of Lincoln ‘minute men’ (whose commander had been roused by Dr Prescott) reached Concord, along with men from Groton and Bedford. When news of Lexington arrived, 150 men marched out to find the regulars and met them a mile from town. Seeing themselves outnumbered, the militia turned about and created a bizarre spectacle by leading the regulars into Concord, with the fifes and drums of both formations playing away.

An extract from Essential Histories 45: The American Revolution 1774–1783

The Build-up to War

The Quebec Act of 1774 also played a role in fomenting discontent among rebellious colonists. In an attempt to resolve the future of the French settlements of Quebec, the British government passed an Act that has had repercussions up to the present day. The colony of Quebec was allowed to keep its French language, laws, customs, and Roman Catholic religion intact, with no interference from London. Furthermore, the boundaries of the colony were extended as far west as the Mississippi, encompassing land treaties made between the British government and Indian tribes following the end of the Seven Years’ War. The understanding was that the laws described in the Act would apply to this area, in recognition of the fact that many of the Indian tribes west of the mountains had been allied with France, and had thus been influenced by French customs and converted to the Catholic Church.

The Thirteen Colonies reacted strongly against the Quebec Act. Long-standing prejudice made them deeply distrustful of French Catholics, and many of the colonies resented this incursion into land west of the Appalachian Mountains, which they believed was theirs by right. They protested at being hemmed in by a Catholic colony and denied access to the rich lands to the west.

Many leading figures throughout the colonies felt that their liberties were gradually being worn away. Their dissatisfaction led to the First Continental Congress, formed in Philadelphia to discuss the Coercive Acts, the Quebec Act, and issues in Massachusetts. The First Continental Congress was convened by colonial leaders, including John Adams, George Washington, Samuel Adams, Benjamin Franklin, and Patrick Henry, with the aim of organizing formal, legally recognized opposition to Parliament’s actions. The Congress issued a declaration condemning the Coercive Acts as unjust and unconstitutional, and rejected the appointment of General Gage as governor. The Congress additionally addressed issues of parliamentary control over the colonies, especially with regard to taxation. At this point the Congress was not interested in independence, merely the redress of perceived injustices.

It was not until 4 July 1776 – after the bloodletting of 1775 and early 1776 – that the Second Continental Congress, led by John Hancock, decided to declare independence from Great Britain. From this point, the Thirteen Colonies referred to themselves as “the United States of America”, but as this title was not officially recognized until after the Treaty of Paris in 1783, they will continue to be referred to throughout this work as the Thirteen Colonies.

It is significant that the British government failed to recognize that the formation of the Congress indicated not just a local Massachusetts or New England rebellion, but the beginnings of a large-scale insurrection. The military situation in North America began to worsen as 1774 drew to a close. British regulars were stationed in Boston. The Quartering Act came into effect once again, increasing tension between civilians and soldiers. The delegates of the First Congress, although they considered military action a last resort, did not help the situation by calling on colonial militia to strengthen and drill more frequently. Weapons of various sizes were seized by colonists and stored away. Royal government representatives were slowly being replaced by committees who supported the conclusions of the First Continental Congress. The colonies and the British government were moving towards all-out conflict.

Two Extracts from Campaign 37: Boston 1775 – The shot heard around the world

Two Questions

Who fired the first shot? Evidence suggests that it was not anyone on the Common; it may have been a tipsy straggler coming from Buckman’s Tavern, but the finger of suspicion points most strongly at someone acting on orders from Samuel Adams. Why else would Parker, a veteran of the French and Indian wars, line up his men in the open in such a tactically pointless and suicidal position, to face a column of regulars they themselves estimated at over 2000? Adams’ comment on hearing the news (‘Oh what a glorious morning!’) certainly begs the question as to whether Parker’s men were sacrificed for political ends.What motivated the colonials to go to war? In 1775, few people wanted war and even fewer sought independence; that it happened was the result of mistakes and misconceptions on both sides and cynical manipulation by a small group with vested interests. Revolutionary myths still endure, but an interview in 1842 between the US historian, Mellen Chamberlain, and a survivor of the fight at Concord bridge, Captain Preston (then 91) is enlightening. It went as follows:

C: Did you take up arms against intolerable oppressions?

P: Oppressions? I didn’t feel them.

C: Were you not oppressed by the Stamp Act?

P: I never saw one... certainly never paid a penny for one of them.

C: Well, what about the Tea Tax?

P: I never drank a drop of the stuff!

C: Then I suppose you had been reading about the eternal principles of liberty?

P: We read only the Bible, The Catechism, Watts’ Psalms and Hymns, and the Almanac.

C: Well then... what did you mean in going to the fight?

P: What we meant was this: we had always governed ourselves and we always meant to.

No comments:

Post a Comment