https://ospreypublishing.com/thisweekhistory/

Constantinople was built by the first Christian Roman Emperor, Constantine, in AD 325 as the Christian equivalent in the east to Rome, the capital of the western empire. Built on the strategically crucial site of ancient Byzantium, it controlled the entrance to the Black Sea as well as the east-west route from Europe to Asia Minor (modern Turkey). Surrounded by water on three sides, it was easy to defend and difficult to cut off entirely in a siege. Springs provided fresh water inside the walls, and fields between the circuits of walls provided food throughout attacks. Successive emperors of the eastern Roman Empire improved and added to the circuits of walls and defences. It was attacked on many occasions, by Roman and barbarian forces, but was only taken twice, once by the Latins in the Fourth Crusade, who held it for 50 years before the Nicaeans regained it, and then in 1453. The importance of Constantinople as an impregnable capital grew after the collapse of the western Roman Empire in the 5th century, as the eastern Roman Empire found itself with few allies. The Byzantine Empire fought its way through the centuries, sometimes on the offensive, often on the defensive, until it eventually went into a final slow decline in the 14th and 15th centuries, threatened by Serbia’s growing power, and then that of the Ottoman Turks.

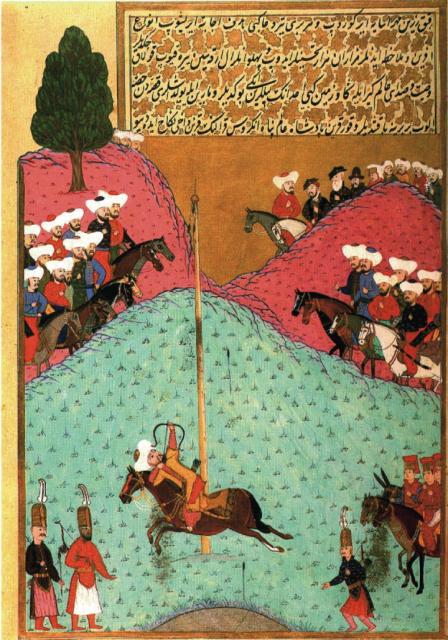

Sułtan Murad II ćwiczy strzelanie z łuku, miniatura turecka, XVI w. Sułtan Murad II, rycina XVI w.

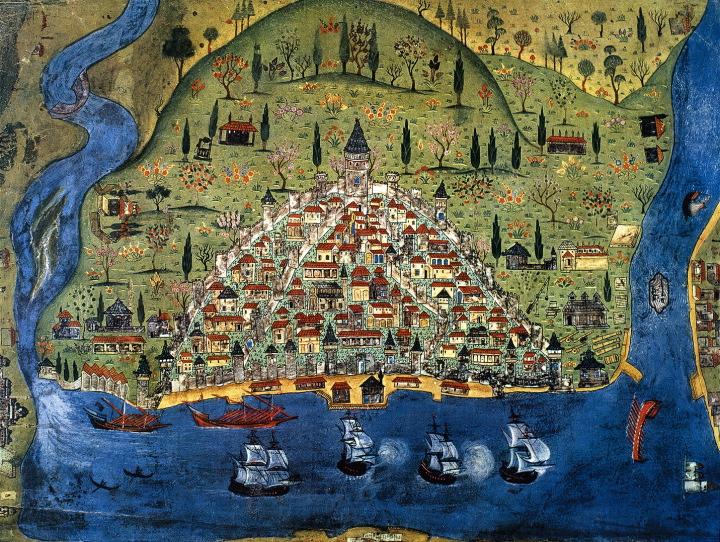

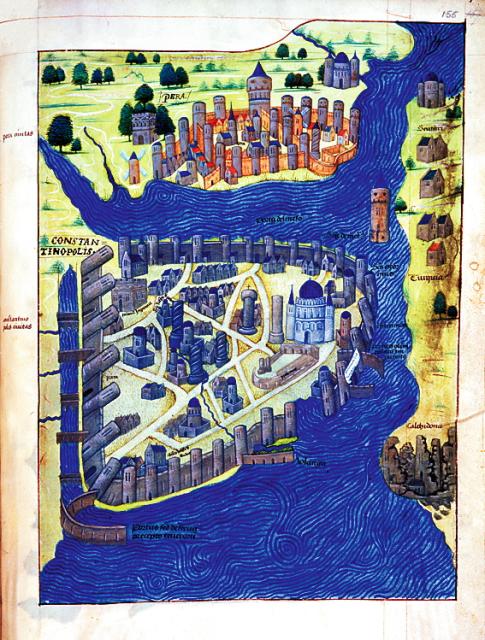

Statki pod Konstantynopolem, miniatura z połowy XIV w Konstantynopol, rycina z „Kroniki Norymberskiej”, koniec XV w. Widok Konstantynopola z XV w.

Mury obronne Konstantynopola

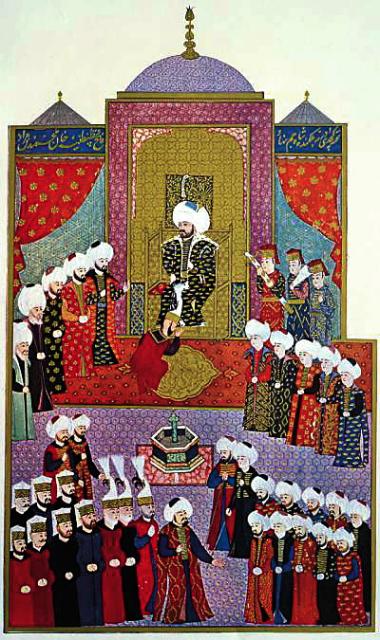

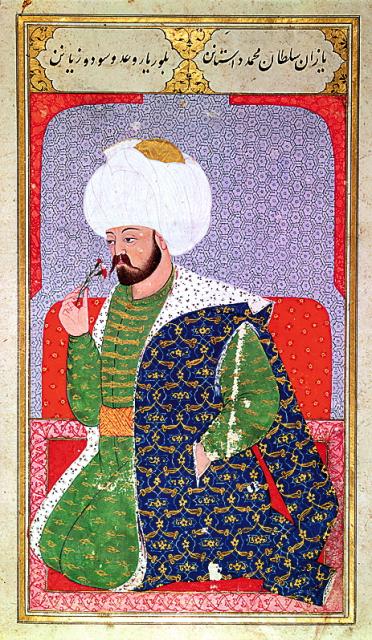

Mehmed II w otoczeniu dostojnikow, miniatura turecka, XVI w. Sułtan Mehmed II, miniatura turecka, XVI w Flota osmańska blokuje port w Marsylii w 1454 r., miniatura turecka, XVI w. Osmańska twierdza Rumeli Hissar nad Bosforem wzniesiona na rozkaz Mehmeda II Flota turecka pod murami Konstantynopola, litografia francuska, XIX w.

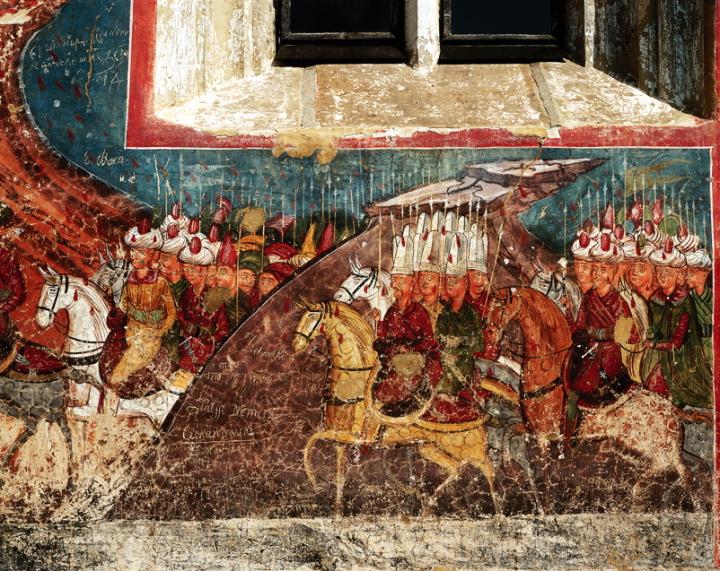

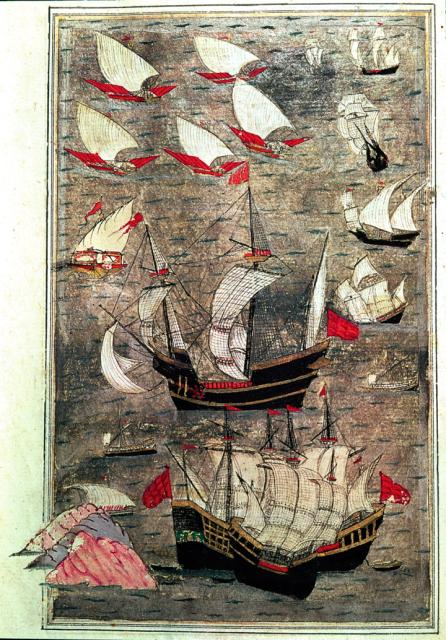

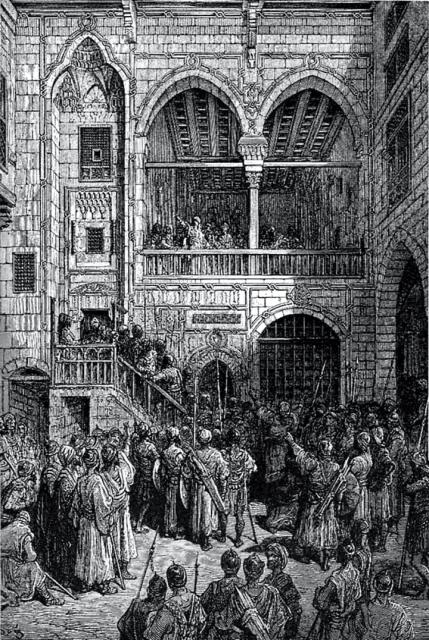

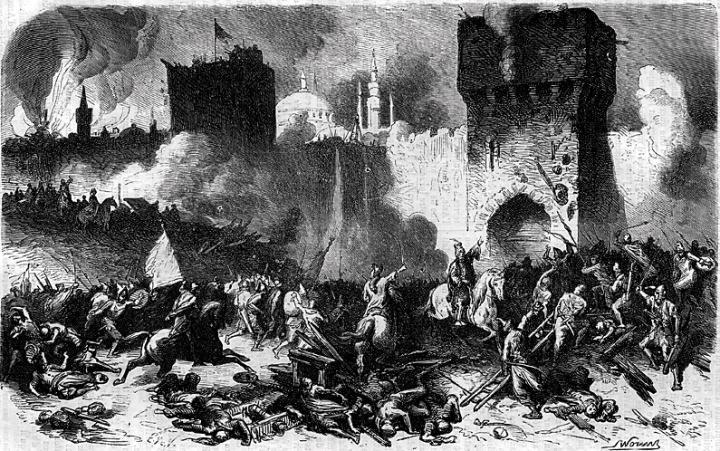

Oblężenie Konstantynopola w 1453 r., malowidło na ścianie cerkwi św. Jerzego w klasztorze Voronet w Rumunii Turecka jazda pod Konstantynopolem, malowidło na ścianie cerkwi św. Jerzego w klasztorze Voronet w Rumunii Kolczuga turecka, XV w. Tarcza turecka inkrustowana złotem i drogimi kamieniami, ok. 1540 r. Oblężenie Konstantynopola przez Turków, miniatura francuska, II połowa XV w. Flota osmańska, miniatura turecka, XVI w. Cesarz Konstantyn XI pozdrawia swych żołnierzy, grafika, XIX w. Tzw. działo z Dardaneli odlane w 1464 r. przez ludwisarzy Mehmeda II – podobne monstrum 11 lat wcześniej ostrzeliwało Konstantynopol Ruiny pałacu Blacherny (dziś Tekfur) i murów obronnych Konstantynopola Mehmed II obserwuje przetaczanie okrętów do zatoki Złoty Róg Przeciąganie tureckich okrętów po lądzie do Złotego Rogu, rycina, XVII w. Turcy przechodzą przez zatokę Złoty Róg po moście pontonowym, miniatura francuska, 1455 r. Szturm Konstantynopola, 29 maja 1453 r., litografia francuska, XIX w.

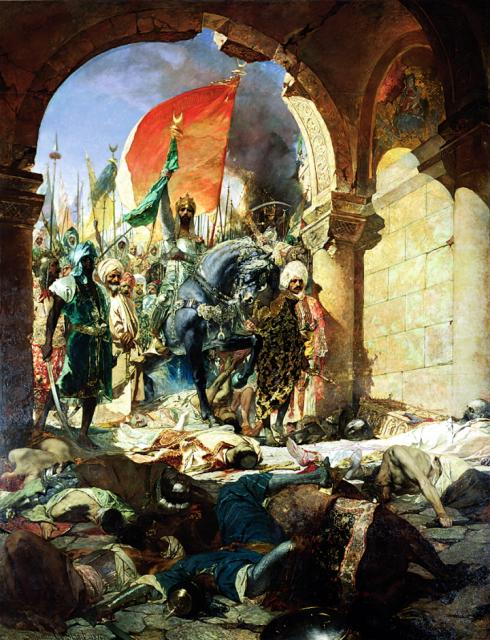

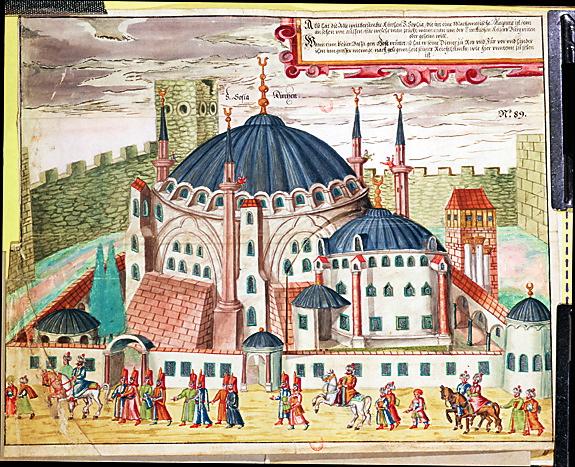

Mehmed II wkracza do Konstantynopola 29 maja 1453 r., mal. Jean-Joseph Benjamin Constant, XIX w Kościół Hagia Sofia w Konstantynopolu zamieniony przez Turków w meczet, akwarela niemiecka, XVI w Widok Istambułu w XVI w., rycina niemiecka z epoki Turcy dokonują rzezi obrońców Konstantynopola, rycina niemiecka, XVII w.

By the time of the Ottoman siege in 1453, Byzantium was an empire in name only, and its only secure territory was that which lay within the walls of Constantinople itself. The Turks had taken all of the Empire’s territory in Asia Minor, and was now moving into Europe. The Turks had wanted to besiege Constantinople since 1401, when they were unable to because of the appearance of enemy Mongol forces in Asia Minor. Despite the desperate attempts of the Byzantine Emperor, John VIII, to gather military support in Europe and halt the Turks, Sultan Mehmet II set about the siege of Constantinople in April 1453. The defences of the city withstood weeks of siege, and the remaining troops of the Empire managed to withstand the attackers from land and sea until 29 May 1453, when the elite janissary units finally breached the walls. The last emperor, Constantine XI, died fighting on the ramparts while leading a valiant counterattack.

Constantinople, under its Turkicised name ‘Istanbul’, became the new Ottoman capital. The remaining Byzantine provinces fell into Turkish hands over the next few years, and the eastern Roman Empire was no more.

Further reading:Essential Histories 33: Byzantium at War AD 600–1453 is a study of the way in which the eastern Roman Empire at war determined the evolution of the state and its structures. For information about the empire that preceded Byzantium, and that built Constantinople, turn to Essential Histories 21: Rome at War AD 293–696. For a more comprehensive overview of the decline and fall of the Roman Empire, read the recently published Rome at War, which details the wars that shaped the Roman Empire, from the Gallic Wars of Julius Caesar, through to the expansion and decline of the empire. For the last chapter in the history of Byzantium and Constantinople, Campaign 78: Constantinople 1453 – The End of Byzantium (extract below) details the four-month siege.

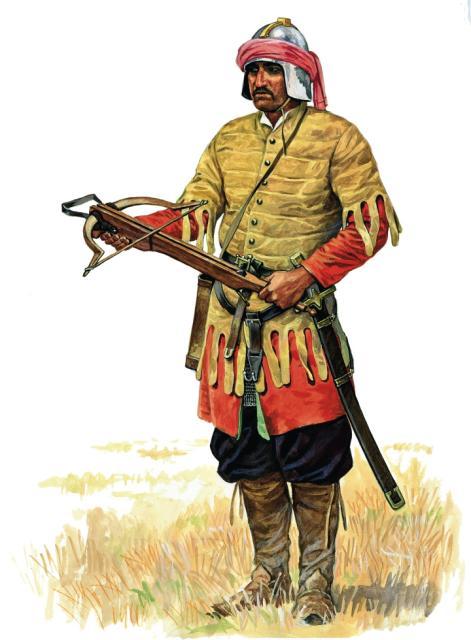

In Elite 58: The Janissaries, Dr David Nicolle examines in detail these elite Turkish troops, recruited entirely from slaves, including prisoners of war who had been enslaved by the Turks, who were converted to Islam and trained under the strictest discipline. Men-at-Arms 140: Armies of the Ottoman Turks 1300-1774 places the Janissaries into context.

New Vanguard 69: Medieval Siege Weapons (2) Byzantium, the Islamic World & India AD 476-1526 looks at the different weapons used in this period, including those used during the siege of Constantinople. It also highlights the flow of ideas between these competing cultures, and the resulting advances in military technologies in this period.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

An extract from Campaign 78: Constantinople 1453 – The End of Byzantium

The fall of the city

On 26 May Sultan Mehmet called a council of war. Çandarli Halil still argued in favour of a compromise and emphasised the continuing danger from the West, but Zaganos Pasha insisted that this time the Ottomans’ western foes would not unite. He also pointed out that Mehmet’s hero, Alexander the Great, had conquered half the world when still a young man. So Mehmet sent Zaganos Pasha to sound out the opinions of the men, perhaps knowing full well what answer he would bring. The following day Mehmet toured the army, while heralds announced a final assault by land and sea on 29 May. Celebration bonfires were lit and from 26 May there was continuous feasting in the Ottoman camp. Criers announced that the first man on to the wall of Constantinople would be rewarded with high rank, and religious leaders told the soldiers about the famous Companion of the Prophet Muhammad, Abu Ayyub, who had died during the first Arab-Islamic attack upon Constantinople in 672. In fact, the defenders saw so many torches that some thought the enemy were burning their tents before retreating. At midnight all lights were extinguished and work ceased. The defenders, however, spent the night repairing and strengthening breaches in the wall. Giustiniani Longo also sent a message to Loukas Notaras, requesting his reserve of artillery. Notaras refused, Longo accused him of treachery and they almost came to blows until the emperor intervened.

The following day was dedicated to rest in the siege lines while Sultan Mehmet visited every unit including the fleet. Final orders were sent to the Ottoman commanders.

Late that afternoon as the setting sun shone in the defenders’ eyes, the Ottomans began to fill the fosse while the artillery was brought as close as possible. The Ottoman ships in the Golden Horn spaced themselves between the Xyloporta and Horaia Gate, while those outside the boom spread more widely as far as the Langa harbour. It began to rain but work continued until around 1.30 in the morning of 29 May.

About three hours before dawn on 29 May there was a ripple of fire from the Ottoman artillery, and Ottoman irregulars swept forward led, according to Alexander Ypsilanti, by Mustafa Pasha. The main attack focused around the battered Gate of St Romanus, where Giustiniani Longo had taken 3,000 troops to the outer wall. Despite terrible casualties, few Ottoman volunteers retreated until, after two hours of fighting, Sultan Mehmet ordered a withdrawal. Ottoman ships similarly attempted to get close enough to erect scaling ladders, but generally failed.

After another artillery bombardment it was the turn of the provincial troops. They included Anatolian troops in fine armour who attacked the St Romanus Gate area at the centre. They marched forward carrying torches in the pre-dawn gloom, but were hampered by the narrowness of the breaches in Constantinople’s walls. More disciplined than the irregulars, they occasionally pulled back to allow their artillery to fire, and during one such bombardment a section of defensive stockade was brought down. Three hundred Anatolians immediately charged through the gap but were driven off. Elsewhere fighting was particularly intense at the Blachernae walls. This second assault continued until an hour before dawn when it was called off.

Sultan Mehmet now had only one fresh corps – his own palace regiments including the Janissaries. According to Ypsilanti, uncorroborated by any other known source, the 3,000 Janissaries were led by Baltaoglu as they attacked the main breach near the St Romanus Gate. All sources agree that these Janissaries advanced with terrifying discipline, moving slowly and without noise or music, while Sultan Mehmet accompanied them as far as the edge of the fosse. This third phase of fighting lasted an hour before some Janissaries on the left found that the Kerkoporta postern had not been properly closed after the last sortie. About 50 soldiers broke in, rushed up the internal stairs and raised their banner on the battlements. They were nevertheless cut off and were in danger of extermination when the Ottomans had a stroke of luck which their discipline and command structure enabled them to exploit fully.

Giovanni Giustiniani Longo was on one of the wooden ramparts in the breach when he was struck by a bullet. This went through the back of his arm into his cuirass, probably through the arm-hole – a mortal wound though none yet realised it – and he withdrew to the rear. The Emperor Constantine was nearby and called out: ‘My brother, fight bravely. Do not forsake us in our distress. The salvation of the City depends on you. Return to your post. Where are you going?’ Giustiniani simply replied: ‘Where God himself will lead these Turks.’ When Giustiniani’s men saw him leave, they thought he was running away. Panic spread, spurred on by the sight of an Ottoman banner on the wall to the north; and those outside the main walls rushed back in an attempt to retreat through the breaches.

Precisely what happened next is obscured by legend. Sultan Mehmet and Zaganos Pasha are both credited with seeing the confusion and sending a unit of Janissaries, led by another man of giant stature named Hasan of Ulubad, to seize the wall. Hasan reached the top of the breach but was felled by a stone. Seventeen of his 30 comrades were also slain but the remainder stood firm until other soldiers joined them.

Janissaries now took the inner wall near the St Romanus Gate and by appearing behind the defenders added still further to their panic. Word now spread that the Ottomans had broken in via the harbour, which may or may not have been true. The time was about four o’clock in the morning and dawn was breaking as yet more Ottoman banners appeared on the Blachernae walls. The Bocchiardi brothers cut their way back to their ships but Minotto and most of the Venetians were captured. According to Doukas, the defenders of the Golden Horn wall escaped over the wall while Ottoman sailors swarmed in the opposite direction.

The defence now collapsed. Foreigners tried to reach their ships in the Golden Horn while local Greek militiamen hurried to defend their own homes. Many defenders in the Lycus Valley were captured. The Studion and Psamathia quarters surrendered to the first proper Ottoman troops who appeared, and so retained their churches undamaged. The Catalans below the Old Palace were all killed or captured, which suggests they were cut off when Ottoman sailors broke through the Plataea and Horaia gates.

There are two basic versions of the death of the Emperor Constantine XI. One maintains that he and his companions charged into the fray as Ottoman soldiers poured through the main breach near the St Romanus Gate. Constantine supposedly shouted: ‘Is there no Christian here who will take my head?’ before being struck in the face and back. A different version is recounted by Tursun Bey and Ibn Kemal. This suggests that a band of naval azaps had dressed themselves as Janissaries so that they could enter the city after Mehmet issued his order preventing any but authorised units going beyond the main wall. They then came across the emperor near the Golden Gate and killed him before realising who he was. Perhaps Constantine was heading towards a tiny harbour just inside the point where the Sea of Marmara walls joined the land-walls, looking for a boat to take him to the Despotate of the Morea.

It is clear that some areas inside Constantinople resisted the first looters before surrendering to regular troops who were sent into the city while the bulk of the army remained outside. Mehmet’s soldiers now advanced methodically, taking control and protecting each quarter from looters. Nevertheless, sailors or marines did enter via the other walls, looting Constantinople on a massive scale before regular troops forcibly stopped them. The rich Orthodox churches and monasteries suffered worst, but the survival of the Church of the Holy Apostles, despite being on the main road to the centre of the city, suggests that the sultan intended to keep it as the main Orthodox church while converting Santa Sofia into Constantinople’s greatest mosque. In fact the ordinary people were treated better by their Ottoman conquerors than their ancestors had been by Crusaders back in 1204; only about 4,000 Greeks died in the siege. Many members of the élite fled into Santa Sofia, apparently believing an ancient prophecy that the infidels would turn tail at the last minute and be pursued back beyond Persia. Instead, Ottoman looters broke down the doors and dragged the people off for ransom.

The sultan himself remained outside the land-walls until about noon on 29 May, when he finally rode to Santa Sofia. There he stopped further damage, had the venerable building converted into a mosque, then joined other worshippers in afternoon prayers. According to Tursun Bey, Mehmet went outside the dome to survey the decrepit state of Constantinople and quote a verse by the Persian poet Firdawsi: ‘The spider serves as gate-keeper in Khusrau’s hall, the owl plays his music in the palace of Afrasiyab.’ Later that afternoon Loukas Notaras was brought before the sultan and apparently reported that the Grand Vizier, Çandarli Halil, had been encouraging the defenders to resist during the course of the siege. In return Mehmet promised to place the old man at the head of the city’s civil administration. Mehmet also had a list of captured officials drawn up and personally paid their ransoms.

On 30 May Sultan Mehmet took the opportunity of removing his independent-minded Grand Vizier, Çandarli Halil. He was replaced by the ultra-loyal Zaganos Pasha, who next day negotiated the surrender of Galata. On 1 June the outlying castles of Silivri and Epibatos surrendered peacefully. Mehmet also ordered all looting to stop and sent his troops back outside the walls. The siege was concluded.

Constantinople was built by the first Christian Roman Emperor, Constantine, in AD 325 as the Christian equivalent in the east to Rome, the capital of the western empire. Built on the strategically crucial site of ancient Byzantium, it controlled the entrance to the Black Sea as well as the east-west route from Europe to Asia Minor (modern Turkey). Surrounded by water on three sides, it was easy to defend and difficult to cut off entirely in a siege. Springs provided fresh water inside the walls, and fields between the circuits of walls provided food throughout attacks. Successive emperors of the eastern Roman Empire improved and added to the circuits of walls and defences. It was attacked on many occasions, by Roman and barbarian forces, but was only taken twice, once by the Latins in the Fourth Crusade, who held it for 50 years before the Nicaeans regained it, and then in 1453. The importance of Constantinople as an impregnable capital grew after the collapse of the western Roman Empire in the 5th century, as the eastern Roman Empire found itself with few allies. The Byzantine Empire fought its way through the centuries, sometimes on the offensive, often on the defensive, until it eventually went into a final slow decline in the 14th and 15th centuries, threatened by Serbia’s growing power, and then that of the Ottoman Turks.

Sułtan Murad II ćwiczy strzelanie z łuku, miniatura turecka, XVI w. Sułtan Murad II, rycina XVI w.

Statki pod Konstantynopolem, miniatura z połowy XIV w Konstantynopol, rycina z „Kroniki Norymberskiej”, koniec XV w. Widok Konstantynopola z XV w.

Mehmed II w otoczeniu dostojnikow, miniatura turecka, XVI w. Sułtan Mehmed II, miniatura turecka, XVI w Flota osmańska blokuje port w Marsylii w 1454 r., miniatura turecka, XVI w. Osmańska twierdza Rumeli Hissar nad Bosforem wzniesiona na rozkaz Mehmeda II Flota turecka pod murami Konstantynopola, litografia francuska, XIX w.

Oblężenie Konstantynopola w 1453 r., malowidło na ścianie cerkwi św. Jerzego w klasztorze Voronet w Rumunii Turecka jazda pod Konstantynopolem, malowidło na ścianie cerkwi św. Jerzego w klasztorze Voronet w Rumunii Kolczuga turecka, XV w. Tarcza turecka inkrustowana złotem i drogimi kamieniami, ok. 1540 r. Oblężenie Konstantynopola przez Turków, miniatura francuska, II połowa XV w. Flota osmańska, miniatura turecka, XVI w. Cesarz Konstantyn XI pozdrawia swych żołnierzy, grafika, XIX w. Tzw. działo z Dardaneli odlane w 1464 r. przez ludwisarzy Mehmeda II – podobne monstrum 11 lat wcześniej ostrzeliwało Konstantynopol Ruiny pałacu Blacherny (dziś Tekfur) i murów obronnych Konstantynopola Mehmed II obserwuje przetaczanie okrętów do zatoki Złoty Róg Przeciąganie tureckich okrętów po lądzie do Złotego Rogu, rycina, XVII w. Turcy przechodzą przez zatokę Złoty Róg po moście pontonowym, miniatura francuska, 1455 r. Szturm Konstantynopola, 29 maja 1453 r., litografia francuska, XIX w.

Mehmed II wkracza do Konstantynopola 29 maja 1453 r., mal. Jean-Joseph Benjamin Constant, XIX w Kościół Hagia Sofia w Konstantynopolu zamieniony przez Turków w meczet, akwarela niemiecka, XVI w Widok Istambułu w XVI w., rycina niemiecka z epoki Turcy dokonują rzezi obrońców Konstantynopola, rycina niemiecka, XVII w.

By the time of the Ottoman siege in 1453, Byzantium was an empire in name only, and its only secure territory was that which lay within the walls of Constantinople itself. The Turks had taken all of the Empire’s territory in Asia Minor, and was now moving into Europe. The Turks had wanted to besiege Constantinople since 1401, when they were unable to because of the appearance of enemy Mongol forces in Asia Minor. Despite the desperate attempts of the Byzantine Emperor, John VIII, to gather military support in Europe and halt the Turks, Sultan Mehmet II set about the siege of Constantinople in April 1453. The defences of the city withstood weeks of siege, and the remaining troops of the Empire managed to withstand the attackers from land and sea until 29 May 1453, when the elite janissary units finally breached the walls. The last emperor, Constantine XI, died fighting on the ramparts while leading a valiant counterattack.

Constantinople, under its Turkicised name ‘Istanbul’, became the new Ottoman capital. The remaining Byzantine provinces fell into Turkish hands over the next few years, and the eastern Roman Empire was no more.

Further reading:Essential Histories 33: Byzantium at War AD 600–1453 is a study of the way in which the eastern Roman Empire at war determined the evolution of the state and its structures. For information about the empire that preceded Byzantium, and that built Constantinople, turn to Essential Histories 21: Rome at War AD 293–696. For a more comprehensive overview of the decline and fall of the Roman Empire, read the recently published Rome at War, which details the wars that shaped the Roman Empire, from the Gallic Wars of Julius Caesar, through to the expansion and decline of the empire. For the last chapter in the history of Byzantium and Constantinople, Campaign 78: Constantinople 1453 – The End of Byzantium (extract below) details the four-month siege.

In Elite 58: The Janissaries, Dr David Nicolle examines in detail these elite Turkish troops, recruited entirely from slaves, including prisoners of war who had been enslaved by the Turks, who were converted to Islam and trained under the strictest discipline. Men-at-Arms 140: Armies of the Ottoman Turks 1300-1774 places the Janissaries into context.

New Vanguard 69: Medieval Siege Weapons (2) Byzantium, the Islamic World & India AD 476-1526 looks at the different weapons used in this period, including those used during the siege of Constantinople. It also highlights the flow of ideas between these competing cultures, and the resulting advances in military technologies in this period.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

An extract from Campaign 78: Constantinople 1453 – The End of Byzantium

The fall of the city

On 26 May Sultan Mehmet called a council of war. Çandarli Halil still argued in favour of a compromise and emphasised the continuing danger from the West, but Zaganos Pasha insisted that this time the Ottomans’ western foes would not unite. He also pointed out that Mehmet’s hero, Alexander the Great, had conquered half the world when still a young man. So Mehmet sent Zaganos Pasha to sound out the opinions of the men, perhaps knowing full well what answer he would bring. The following day Mehmet toured the army, while heralds announced a final assault by land and sea on 29 May. Celebration bonfires were lit and from 26 May there was continuous feasting in the Ottoman camp. Criers announced that the first man on to the wall of Constantinople would be rewarded with high rank, and religious leaders told the soldiers about the famous Companion of the Prophet Muhammad, Abu Ayyub, who had died during the first Arab-Islamic attack upon Constantinople in 672. In fact, the defenders saw so many torches that some thought the enemy were burning their tents before retreating. At midnight all lights were extinguished and work ceased. The defenders, however, spent the night repairing and strengthening breaches in the wall. Giustiniani Longo also sent a message to Loukas Notaras, requesting his reserve of artillery. Notaras refused, Longo accused him of treachery and they almost came to blows until the emperor intervened.

The following day was dedicated to rest in the siege lines while Sultan Mehmet visited every unit including the fleet. Final orders were sent to the Ottoman commanders.

Late that afternoon as the setting sun shone in the defenders’ eyes, the Ottomans began to fill the fosse while the artillery was brought as close as possible. The Ottoman ships in the Golden Horn spaced themselves between the Xyloporta and Horaia Gate, while those outside the boom spread more widely as far as the Langa harbour. It began to rain but work continued until around 1.30 in the morning of 29 May.

About three hours before dawn on 29 May there was a ripple of fire from the Ottoman artillery, and Ottoman irregulars swept forward led, according to Alexander Ypsilanti, by Mustafa Pasha. The main attack focused around the battered Gate of St Romanus, where Giustiniani Longo had taken 3,000 troops to the outer wall. Despite terrible casualties, few Ottoman volunteers retreated until, after two hours of fighting, Sultan Mehmet ordered a withdrawal. Ottoman ships similarly attempted to get close enough to erect scaling ladders, but generally failed.

After another artillery bombardment it was the turn of the provincial troops. They included Anatolian troops in fine armour who attacked the St Romanus Gate area at the centre. They marched forward carrying torches in the pre-dawn gloom, but were hampered by the narrowness of the breaches in Constantinople’s walls. More disciplined than the irregulars, they occasionally pulled back to allow their artillery to fire, and during one such bombardment a section of defensive stockade was brought down. Three hundred Anatolians immediately charged through the gap but were driven off. Elsewhere fighting was particularly intense at the Blachernae walls. This second assault continued until an hour before dawn when it was called off.

Sultan Mehmet now had only one fresh corps – his own palace regiments including the Janissaries. According to Ypsilanti, uncorroborated by any other known source, the 3,000 Janissaries were led by Baltaoglu as they attacked the main breach near the St Romanus Gate. All sources agree that these Janissaries advanced with terrifying discipline, moving slowly and without noise or music, while Sultan Mehmet accompanied them as far as the edge of the fosse. This third phase of fighting lasted an hour before some Janissaries on the left found that the Kerkoporta postern had not been properly closed after the last sortie. About 50 soldiers broke in, rushed up the internal stairs and raised their banner on the battlements. They were nevertheless cut off and were in danger of extermination when the Ottomans had a stroke of luck which their discipline and command structure enabled them to exploit fully.

Giovanni Giustiniani Longo was on one of the wooden ramparts in the breach when he was struck by a bullet. This went through the back of his arm into his cuirass, probably through the arm-hole – a mortal wound though none yet realised it – and he withdrew to the rear. The Emperor Constantine was nearby and called out: ‘My brother, fight bravely. Do not forsake us in our distress. The salvation of the City depends on you. Return to your post. Where are you going?’ Giustiniani simply replied: ‘Where God himself will lead these Turks.’ When Giustiniani’s men saw him leave, they thought he was running away. Panic spread, spurred on by the sight of an Ottoman banner on the wall to the north; and those outside the main walls rushed back in an attempt to retreat through the breaches.

Precisely what happened next is obscured by legend. Sultan Mehmet and Zaganos Pasha are both credited with seeing the confusion and sending a unit of Janissaries, led by another man of giant stature named Hasan of Ulubad, to seize the wall. Hasan reached the top of the breach but was felled by a stone. Seventeen of his 30 comrades were also slain but the remainder stood firm until other soldiers joined them.

Janissaries now took the inner wall near the St Romanus Gate and by appearing behind the defenders added still further to their panic. Word now spread that the Ottomans had broken in via the harbour, which may or may not have been true. The time was about four o’clock in the morning and dawn was breaking as yet more Ottoman banners appeared on the Blachernae walls. The Bocchiardi brothers cut their way back to their ships but Minotto and most of the Venetians were captured. According to Doukas, the defenders of the Golden Horn wall escaped over the wall while Ottoman sailors swarmed in the opposite direction.

The defence now collapsed. Foreigners tried to reach their ships in the Golden Horn while local Greek militiamen hurried to defend their own homes. Many defenders in the Lycus Valley were captured. The Studion and Psamathia quarters surrendered to the first proper Ottoman troops who appeared, and so retained their churches undamaged. The Catalans below the Old Palace were all killed or captured, which suggests they were cut off when Ottoman sailors broke through the Plataea and Horaia gates.

There are two basic versions of the death of the Emperor Constantine XI. One maintains that he and his companions charged into the fray as Ottoman soldiers poured through the main breach near the St Romanus Gate. Constantine supposedly shouted: ‘Is there no Christian here who will take my head?’ before being struck in the face and back. A different version is recounted by Tursun Bey and Ibn Kemal. This suggests that a band of naval azaps had dressed themselves as Janissaries so that they could enter the city after Mehmet issued his order preventing any but authorised units going beyond the main wall. They then came across the emperor near the Golden Gate and killed him before realising who he was. Perhaps Constantine was heading towards a tiny harbour just inside the point where the Sea of Marmara walls joined the land-walls, looking for a boat to take him to the Despotate of the Morea.

It is clear that some areas inside Constantinople resisted the first looters before surrendering to regular troops who were sent into the city while the bulk of the army remained outside. Mehmet’s soldiers now advanced methodically, taking control and protecting each quarter from looters. Nevertheless, sailors or marines did enter via the other walls, looting Constantinople on a massive scale before regular troops forcibly stopped them. The rich Orthodox churches and monasteries suffered worst, but the survival of the Church of the Holy Apostles, despite being on the main road to the centre of the city, suggests that the sultan intended to keep it as the main Orthodox church while converting Santa Sofia into Constantinople’s greatest mosque. In fact the ordinary people were treated better by their Ottoman conquerors than their ancestors had been by Crusaders back in 1204; only about 4,000 Greeks died in the siege. Many members of the élite fled into Santa Sofia, apparently believing an ancient prophecy that the infidels would turn tail at the last minute and be pursued back beyond Persia. Instead, Ottoman looters broke down the doors and dragged the people off for ransom.

The sultan himself remained outside the land-walls until about noon on 29 May, when he finally rode to Santa Sofia. There he stopped further damage, had the venerable building converted into a mosque, then joined other worshippers in afternoon prayers. According to Tursun Bey, Mehmet went outside the dome to survey the decrepit state of Constantinople and quote a verse by the Persian poet Firdawsi: ‘The spider serves as gate-keeper in Khusrau’s hall, the owl plays his music in the palace of Afrasiyab.’ Later that afternoon Loukas Notaras was brought before the sultan and apparently reported that the Grand Vizier, Çandarli Halil, had been encouraging the defenders to resist during the course of the siege. In return Mehmet promised to place the old man at the head of the city’s civil administration. Mehmet also had a list of captured officials drawn up and personally paid their ransoms.

On 30 May Sultan Mehmet took the opportunity of removing his independent-minded Grand Vizier, Çandarli Halil. He was replaced by the ultra-loyal Zaganos Pasha, who next day negotiated the surrender of Galata. On 1 June the outlying castles of Silivri and Epibatos surrendered peacefully. Mehmet also ordered all looting to stop and sent his troops back outside the walls. The siege was concluded.

No comments:

Post a Comment