https://ospreypublishing.com/thisweekhistory/

Rosyjski port wojenny w Sewastopolu ok. 1850 r.

Cesarz Francuzów Napoleon III odwiedza w Calais flotę brytyjską szykującą się do rejsu na Morze Czarne, litografia z epoki

Brytyjska eskadra ostrzeliwuje rosyjską twierdzę Bomersund na Wyspach Alandzkich w sierpniu 1854 r., litografia z epoki

Car Mikołaj I w mundurze galowym

Cesarz Francuzów Napoleon III, mal. Franz Xaver Winterhalter

Królowa Wielkiej Brytanii Wiktoria, portret z 1837 r.

Fotograf Roger Fenton na wozie mieszczącym laboratorium fotograficzne, Krym, 1855 r.

Brytyjscy dragoni i francuscy żuawi w obozie pod Sewastopolem

Brytyjscy oficerowie na Krymie w 1854 r.

Oblężenie Sewastopola – brytyjscy artylerzyści wciągają na stanowisko działo 32-funtowe

Admirał Paweł Nachimow, jeden z dowódców obrony Sewastopola

Ks. Aleksander Mienszykow, dowódca wojsk rosyjskich na Krymie

Artyleria sprzymierzonych bombarduje Sewastopol 1854 r., litografia francuska z epoki

Okręty sprzymierzonych kotwiczą w zatoce pod Bałakławą 1855 r.

Florence Nightingale, fotografia z lat 60. XIX w.

Pielęgniarka opatruje rannego podczas walk pod Sewastopolem w 1855 r.

Florence Nightingale w szpitalu w Scutari, litografia z 1856 r.

Francuska artyleria podczas bitwy nad Almą, rycina z epoki

Oficer 11. pułku huzarów księcia Alberta z Lekkiej Brygady uzbrojony w szablę kawaleryjską wz. 1854

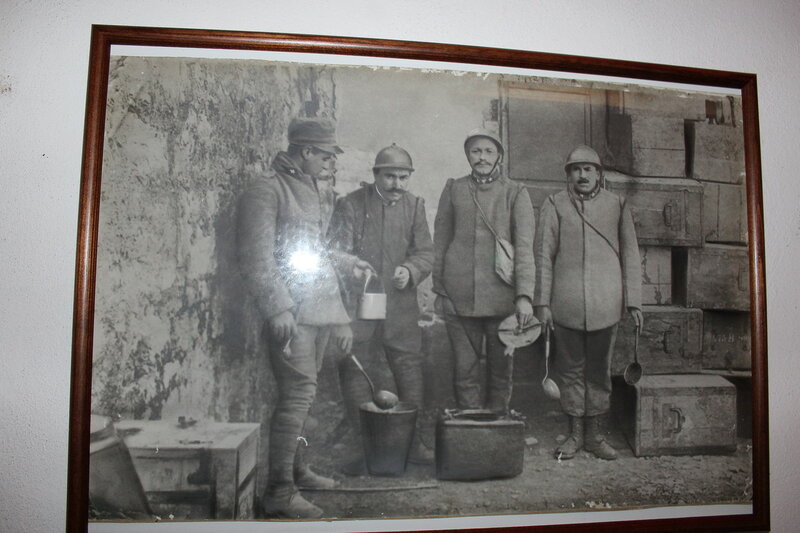

Marynarze walczyli jak zwykła piechota, artylerzyści wznosili także polowe fortyfikacje

Widok Sewastopola, głównej bazy rosyjskiej Floty Czarnomorskiej, 1848 r

Obóz wojsk sprzymierzonych na Krymie, zima 1854 r., rys. C.L. Doughty, XX w.

Flota Czarnomorska na redzie Teodozji, mal. Iwan Ajwazowski, 1850 r.

Bitwa pod Synopą, 30 listopada 1853 r. – rosyjskie okręty liniowe ostrzeliwują eskadrę turecką, mal. Iwan Ajwazowski

Rosyjska twierdza Kale w Gruzji płonie po ostrzale okrętów sprzymierzonych, litografia włoska z epoki

Bitwa pod Synopą, mal. Andriej Bogomołow

Jeszcze jeden obraz bitwy pod Synopą, mal. Iwan Ajwazowski, 1853 r.

Brytyjska flota wypływa ze Spithead na Bałtyk, mal. William Melby, 1854 r.

Sewastopol ostrzeliwany przez sprzymierzonych, rycina francuska, 1855 r.

Bitwa pod Bałakławą, 25 października 1854 r., litografia według rysunku Williama Simpsona

Oddziały tureckie lądują w Eupatorii na Krymie, rycina francuska, 1854 r

Brytyjska lekka brygada szarżuje na rosyjską baterię pod Bałakławą, mal. Richard Caton Woodville, 1897 r.

Okręty sprzymierzonych ostrzeliwują rosyjskie pozycje na Krymie, litografia z epoki

Wyładunek amunicji dla wojsk sprzymierzonych w porcie Bałakława

Rosjanie podpalają budynki przed opuszczeniem Sewastopola

Car Aleksander II i oficerowie lejbgwardii

Rosyjscy artylerzyści na szańcach Sewastopola, litografia z epoki

Flota francuska przepływa przez cieśninę Bosfor w 1855 r., rycina z epoki

Rozbita rosyjska bateria w Sewastopolu

Tureckie okręty liniowe z połowy XIX w

Brytyjski medal za wojnę krymską (awers)

Brytyjski medal za wojnę krymską (rewers)

In 1853, Russia drew the Ottoman Empire into a war on a superficial pretext: the Ottomans had granted Catholic France, rather than Orthodox Russia, the right to protect Ottoman controlled Christian sites in Jerusalem. The Russians claimed this was a provocation of war by the Ottomans – however their true intentions were to claim Ottoman territory.

Anxious to annex territories in Eastern Europe, particularly the provinces of Moldavia and Walachia (now in modern day Romania), Russian troops found themselves near the banks of the Black Sea, occupying parts of the Ottoman Empire. The Turks officially declared war. On 28 March 1854, looking to prevent Russian expansion, and in order to protect their lucrative trade interests in the region, Britain and France (with Austrian backing) also declared war on Russia.

The Crimean War lasted until 1856 and took place mainly on the Crimean peninsula in the Black Sea. The war became infamous for military and logistical incompetence, epitomised by the Charge of the Light Brigade, but was one of the first conflicts to introduce tactical use of railways.

In September 1854, Allied troops invaded the Crimea, having overcome an outbreak of cholera that took a particularly heavy toll on French troops, hampering their preparations for the attack. Within a month, however, French and British troops were besieging the Russian held city of Sebastopol. The siege was to last for a year.

On 25 October 1854, the Russians were driven back at the Battle of Balaclava, despite the foolhardy Charge of the Light Brigade. Eleven days later, the Battle of Inkerman was also fought with high casualties on both sides.

Notably, a violent storm on the night of 14 November 1854 wrecked nearly thirty allied vessels carrying a precious cargo of medical supplies, food and clothing. There followed a desperate winter, pitifully short of supplies, where wounded soldiers lay hungry and gravely in need of medical assistance. This ill-treatment was reported by war correspondents for newspapers from Europe to America. It prompted the work of Florence Nightingale, and led eventually to the introduction of modern nursing methods, but did little to help at the time.

British and French troops suffered immense casualties before a peace treaty was finally written. Over 111,000 British men reached the Crimea of whom, official figures state, 21,097 men died in the theatre of war and 16,323 succumbed to disease, figures that do not include those who died after returning home. The French sent out over 300,000 men of whom 30,240 were killed in action or from wounds, and possibly a further 75,000 died of disease

The French and British finally forced the fall of Sebastopol on 11 September 1855 and peace was subsequently concluded at Paris on 30 March 1856.

The final stages leading to the Treaty of Paris are described here in an extract from Essential Histories 2: The Crimean War 1854-1856

Apart from occasional, ritual exchanges of fire from batteries facing one another across the bay and occasional skirmishes in the Baidar Valley around Sevastopol, 1855 came to an inauspicious close. An enormous explosion in the French lines on 15 November, which killed 80 and wounded almost 300, resulted from mishandling of ammunition not enemy action.

In the opening weeks of 1856, typhus and cholera struck once more, especially among the French, who suffered over 50,000 cases, of which one-fifth died. Paymaster Dixon recorded in January: ‘The French are dreadfully badly off, much worse than last winter, they are dropping off in scores, nay hundreds.’ The British now had an abundance, and in some instances a surplus, of clothing and huts, and as the weather improved they began organising drag hunts and race meetings. Regimental theatres put on plays and a range of speakers delivered educational lectures, too. Militarily, the allies undertook musketry training and field exercises. But it all lacked purpose. In Dixon’s words, ‘road making here and I suppose diplomacy at home have taken its [fighting’s] place’. Soldiers and sailors were marking time until the small print of peace could be fashioned into an acceptable document. French fantasies about attacking Russia’s Polish provinces through Germany and British dreams of reducing Kronstadt and Helsignfors (Helsinki) in the Baltic provided the unrealistic backdrop for negotiation.

Almost throughout the entire war, fitful attempts at securing peace had been going on in Vienna, but during the autumn of 1855 clandestine bilateral contacts were also established between Paris and St Petersburg. Discovery of these prompted Austria to take the initiative. On 16 December 1855, Count Esterhazy led a mission to St Petersburg, which conveyed conditions for peace: confirmation of autonomy for Moldavia and Wallachia; freedom of navigation for all nations on the Danube; neutralisation of the Black Sea, with abolition of military installations on its shores; guarantee of the rights of all Christian subjects in Turkey. A fifth condition, allegedly added on British insistence, provided for further matters to be raised during subsequent talks ‘in the interest of lasting peace’. The Holy Places in Jerusalem, the Bosphorus and Dardanelles Straits or Sevastopol were not highlighted. In that respect, the Tsar would not be humiliated. However, if Russia did not accept the submission by 18 January, Austria threatened war.

Despite some reluctance and opposition among his ministers, two days before the deadline Alexander II accepted these terms. Count D. N. Bludov recalled Louis XIV’s resignation at the conclusion of the Seven Years War in 1763: ‘If we no longer have the means to make war, then let us make peace.’ The news reached Sevastopol eight days later. There was still time for forces on both sides to make military points. On 29 January, Russian guns in Sevastopol’s northern suburb let loose a vast cannonade against the Karabel and on 4 February the French destroyed Fort Nicholas. Honour seemed to be satisfied. Hostilities petered out.

The peace conference gathered in Paris on 25 February 1856, and three days later an armistice lasting until 31 March was signed. The following morning, 29 February, allied and Russian representatives met near Tractir Bridge to discuss the new situation amicably. Reviews of one another’s troops were arranged to celebrate peace, and on 24 March the British commander, Codrington, invited Russian officers to a race meeting near the Tchernaya.

The Treaty of Paris, formally bringing the Crimean War to a close, was signed on 30 March, signalled by a 101-gun salute in the Crimea on 2 April and finally ratified by signatory nations on 27 April. Its provisions referred to ‘the independence and territorial integrity of the Ottoman Empire’ and the Sultan’s ‘generous intentions towards the Christian population of his empire … ameliorating their conditions without distinction of religion or race’. The Black Sea was to be neutralised, ‘in consequence [of which] His Majesty the Emperor of All the Russias and His Imperial Majesty the Sultan engage not to establish or to maintain upon that coast any military–maritime arsenal’. The principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia were to enjoy ‘the privileges and immunities of which they are in possession … under the suzerainty of the Porte … without separate right of interference in their internal affairs … by any of the Guaranteeing Powers’. The principality of Servia would ‘preserve its independence and national administration, as well as full liberty of worship, of legislation, of commerce, and of navigation’.

Prince Albert commented: ‘It is not such as we could have wished; still, infinitely to be preferred to the prosecution of war.’ Queen Victoria consoled herself with the thought that England had saved Europe from ‘the arrogance and pretensions of that barbarous power, Russia’. She ‘disliked the idea of peace’, Lord Clarendon noted, but was ‘reconciled’ to it. France had no such qualms. The Crimean War was a triumph for Napoleon III, who had ‘given France a glorious victory of arms and peace to Europe’.

Further reading

Essential Histories 2:

The Crimean War 1854–1856

This bitter war between Russia and Turkey, aided by Britain and France, was the setting for the stuff of legends of which the gallant Charge of the Light Brigade is probably the best remembered, This richly illustrated book covers the battles of Alma, Balaclava, Inkerman and Sebastopol, and also offers first hand soldier and civilian accounts.

Men-at-Arms 27:

The Russian Army of the Crimea

This book examines the uniforms, equipment, history and organisation of the Russian Army that fought in the Crimean War. Field army, infantry, artillery and cavalry are all covered, together with details of High Command and summaries of key battles. Uniforms are shown in full illustrated detail.

Men-at-Arms 40:

The British Army of the Crimea

The British Army’s involvement in the Crimean War of 1854–56 is often remembered only for the ill-advised ‘charge of the Light Brigade’ during the battle of Sevastopol as memorialized in Tennyson’s poem. Nevertheless, the British Army, together with the French and Turkish armies, posed a formidable threat to Russia’s expansionist ambitions. This book examines the uniforms of the various branches of the British Army involved in the conflict, including general officers and staff, artillery, infantry and the most colourful branch of all – the cavalry. Numerous illustrations, including rare contemporary photographs depict the army's uniforms in vivid detail.

Men-at-Arms 196:

The British Army on Campaign (2) The Crimea 1854–56

In 1854 the British Army was committed to its first major war against a European power since 1815. The ‘Army of the East’ was despatched to check, in alliance with France and later Sardinia, Russian ambitions for an outlet to the Mediterranean.

Campaign 6:

Balaclava 1854: The Charge of the Light BrigadeThe port of Balaclava was crucial in maintaining the supply lines for the Allied siege of Sevastapol. The Russian attack on it on 25 October 1854 therefore posed a major threat to the survival of the Allied cause. John Sweetman looks at the events, including the immortalised charge of the Light Brigade.

Campaign 51:

Inkerman 1854: The Soldiers’ Battle

The third major action of the Crimean War (following Alma and Balaclava), the British victory in heavy fog at Inkerman proved to be a testament to the skill and initiative of the individual men and officers of the day: yet the Russians, although defeated, also successfully stalled a crucial allied offensive.